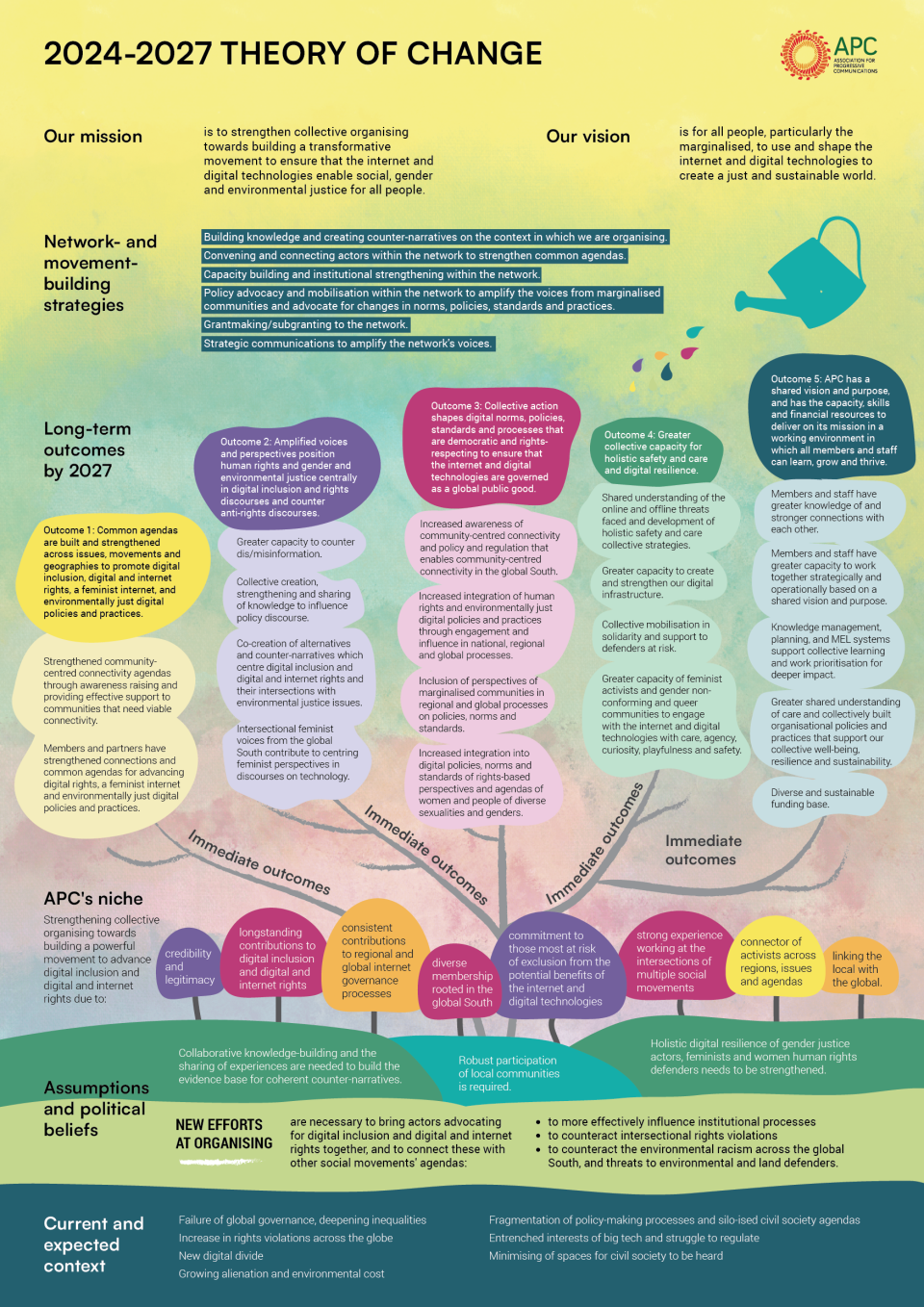

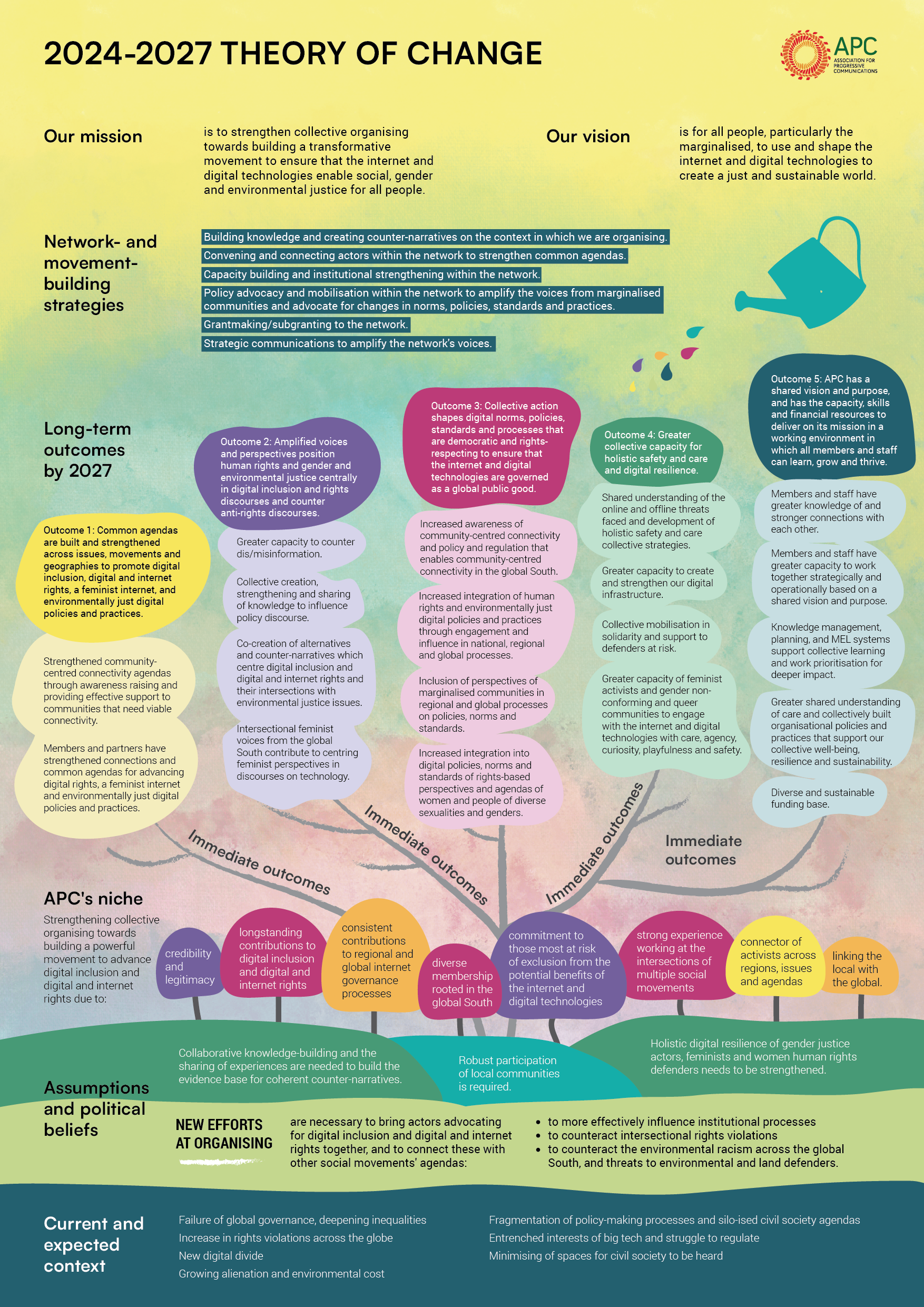

Read APC's full 2024-2027 strategic plan in PDF format or the video presentation, and check this visualisation of our Theory of Change.

INTRODUCTION

The Association for Progressive Communications (APC) is a membership-based network of organisations and activists. It was founded in 1990 to empower individuals, organisations and social movements to use information and communications technologies (ICTs) to build strategic communities to contribute to equitable human development, social justice, participatory political processes and environmental sustainability.

In the consultations to develop APC’s strategic plan for 2024-2027, APC members, staff and partners noted the rapid pace of changes that are taking place in an already vulnerable post-COVID environment. Of particular concern were global geopolitical shifts, regional wars and conflicts, and an intensification of the climate crisis, as well as the speed of the digitalisation of societies, which had resulted in an increase in online surveillance and censorship and catalysed the spread of technology-facilitated violence. A fragmentation in advocacy efforts in the fields of digital inclusion and digital and internet rights was acknowledged, with an increase in the number of diverse actors working on sometimes overlapping causes.

In the previous strategic plan, we realised the need to refocus APC’s vision and mission to leverage the strength of our members, partners and allies to contribute to transforming the systems of oppression and inequality that are being perpetuated and deepened by the ways in which digital technologies are being used and governed. We also identified the need to focus APC’s work more in order to deepen our impact. In the current context, which can be described as one of global distress and uncertainty, we have committed to strengthening collective organising with the aim of building a powerful movement to ensure that the internet and digital technologies enable social, gender and environmental justice for all people.

We believe that by strengthening collective organising in the current global context, civil society actors will be able to push back against the closure of policy and civic spaces, to advocate for inclusive internet agendas based on human rights principles, and to challenge emerging power structures that result in the repression and marginalisation of people.

PROCESS

This strategic plan is the result of a consultative process that builds on the lessons and findings of APC’s mid-term evaluation in 2022, as well as the evaluation of our local access initiative over a five-year period. [2]

The process began with a series of consultations with APC staff, the Board and members to explore their thinking on the changes in the external context, the current state of the field of digital inclusion and digital and internet rights organising, and APC’s niche and role in this context. In response to the key ideas and themes that emerged from these consultations, we then carried out a survey of our members and partners in English, Spanish and French and held interviews with 10 “experts” who know APC well and have a deep understanding of the field. The purpose of the survey and interviews was to further explore questions related to APC’s niche and role, and how APC could deepen its impact in the next five years. We also carried out a mapping of key actors in the field to further inform the process of identifying APC’s niche and positioning in the field.

From this process there emerged a number of key findings which then shaped the revision of our theory of change, a process we carried out in discussion with our staff team. Finally, from the theory of change we developed this draft strategic plan for discussion and feedback from APC staff, the Board and members.

THEORY OF CHANGE

SUMMARY OF CURRENT AND EXPECTED CONTEXT

This Strategic Plan occurs in a context of heightened global distress, and a pervasive sense of uncertainty and rapid change. It is marked by a horrific intensification of violence and an escalation of conflicts such as in Palestine, Israel, Sudan, Ethiopia and Myanmar, and a protracted war in Ukraine. It is a context that is characterised by the rapid digitalisation and datafication of societies, with fragile economies in the global South still attempting to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. It is scarred by a resurgence of right-wing nationalism and fundamentalism in many countries, alongside the legitimisation of misogyny and anti-rights discourses, and the increasing precarity of Black, brown and diverse bodies.

A failure of global governance, deepening inequalities

In 2020, speaking at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for a “New Social Contract, between Governments, people, civil society, business.” [10] His purpose was to address the stark global inequalities made evident by the pandemic, and to offer some way to redress the underlying causes of these inequalities, including historical injustices, “from colonialism and patriarchy to racism and the digital divide.” [11] In doing so, he identified both digitalisation and climate change as likely having the most serious impact on a sustainable future, with both threatening to widen inequalities further if not addressed through concerted global cooperation.

The pandemic had magnified multiple intersecting inequalities, exposing the authoritarian tendencies of many states, as well as the global inequities and hegemonic privileges on issues such as vaccine distribution. [12] As APC stated in its contribution to the UN’s World Public Sector Report 2023, “The COVID-19 pandemic made established and emerging structural challenges related to inequality, discrimination, exclusion and violence more palpable and highlighted tensions around the continuum between the exercise of human rights online and offline.” [13] These tensions were felt through an increase in online surveillance by states and corporations, violations of privacy and personal data rights, threats to freedom of expression including media censorship, and escalating online gender-based violence. [14]

In a context of rapid digitalisation of services and economies as governments tried to respond to the virus, many people, mostly the already excluded, were unable to digitally substitute their activities. In this respect, the pandemic showed the stark effects of the further marginalisation of communities who were not online, including in accessing government services and aid when it was most needed. In response to the online rights violations and threats, and with the socioeconomic impact of the digital divide made clear, many civil society actors across the world called for solidarity with oppressed communities and with colonised populations, for digital rights organisations to work better together, and for cross-sectoral movement building. They argued that it is only through the collective strength of rights-based actors that any significant change will be achieved. It was necessary for digital rights organisations to connect more meaningfully with grassroots communities to ensure greater participation of excluded groups in internet policy development and governance processes. [15]

But instead of the cohesion and solidarity necessary to address global inequalities in a fractured post-COVID environment, the opposite has occurred. In a period that has been accurately described as symptomatic of a “failure of global governance”, [16] geopolitics have become more polarised, particularly around regional wars and conflicts. Despite increasingly urgent warnings by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of a pending climate catastrophe, there remains a chronic lack of attention given to the climate crisis. Attempts at economic recovery have occurred in the context of aggressive stand-offs between superpowers competing for trade supremacy, leveraging national politics and vulnerable economies as proxies in their competition for dominance. Food insecurity has worsened after the start of the war in Ukraine, and human rights abuses, displacement and forced migration have intensified. Rights violations have escalated, with freedom of expression and the right to protest stifled in many countries across the world, while cohesion in national politics in countries has been shattered by divisions.

As stated by a special edition of The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023, published before the recent intensification of violence in Israel and Palestine, the “impacts of the climate crisis, the war in Ukraine, a weak global economy, and the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic” [17] have all impacted negatively on the achievement of the Goals. It notes an increase in global hunger and food insecurity, growing inequalities, and a looming “climate cataclysm”, which the current pace of climate action is insufficient to address. A rise in global poverty, insecurities of livelihoods, and uncertainty of home through forced mass migration and the further displacement of peoples are all anticipated. All of these fractures and divisions play out distinctly for people and communities across the world, and in different ways mitigate against the possibility of global cooperation and solidarity in order to address the pressing issues of the time. In this divided and distressing global context, several key issues are important to the work of APC.

The increase in rights violations across the globe

The growing strength of reactionary and populist politics, as well as authoritarianism, is resulting in an increase in human rights violations and a narrowing of civic space in many countries across the world. In the global South, activists are imprisoned, journalists are persecuted and surveilled, prosecutions and harassment for speaking out online are frequent, and new legislation has been passed to make it difficult for NGOs to operate. [18] Minorities are often the worst affected by these violations, both online and offline. In Uganda, draconian anti-gay legislation threatening homosexuals with the death penalty has been passed, while in other countries online attacks on women and gender-diverse peoples have amplified. Meanwhile, through state collusion with big business, environmental and land defenders working at the grassroots level in many regions in the global South are consistently vulnerable and exposed, including to the threat of assassination.

The rapid digitalisation of societies has assisted this shift to the right, with social media platforms facilitating polarisation through disinformation and propaganda, and censoring through content take-downs. Tech corporations are also complicit in many human rights abuses through the provision of security, monitoring and surveillance technologies to states that turn on their citizens. Many governments use private sector platforms to deliver public services, with few mechanisms ensuring transparency and accountability with respect to privacy, data use and algorithms, or on the nature of the arrangements reached with the platforms. This has aligned the market needs of the private sector with the desire of states to control and manage their citizens and peoples, a trend already evident in the previous strategic plan. The potential of new technologies using artificial intelligence to intensify the information disorder, weaken public trust, and manipulate voters during elections strengthens this complicity, and poses very real threats to democratic stability in countries across the globe.

A new digital divide

The global instability being experienced – particularly with respect to failing economies, the stresses placed on livelihoods, and climate change – is also not likely to be easily mitigated through intensifying the pace of digitalisation and datafication of economies, as some may hope. Instead, as COVID-19 showed, digitalisation resulted in the further marginalisation of unconnected communities, and was not successful in many countries in the world in bringing more people online.

Research has also suggested [19] that a new digital divide is emerging which is insufficiently addressed by stepping up infrastructure roll-out plans. To properly participate in the data economy and its potential for innovation and development, there will be a greater need for affordable, dedicated internet connections, and for meaningful internet access. Without this, not just the unconnected, but those who are “barely online” due to multiple factors including high data costs and the costs of devices, are likely to be left behind, with a rise in global inequalities and new forms of marginalisation as a result. Participation in the digital economy will require broad-based and significant improvements in areas such as education, technical literacy and skills, and urgent action to bring down the cost of access, which governments and regulators in many countries in the global South have, until now, failed to do.

Growing alienation, and environmental cost

The personal and environmental cost of digitalisation affecting all aspects of society and people’s lives has not been properly taken into account. This includes the digital alienation that is the result of the datafication and commodification of personal lives and interactions, and the alienation from the environment that is the result of the massive roll-out and use of technologies. These technologies are dependent for their production on the extraction of raw materials and the displacement of peoples and acquisition of land in the global South, as well as exploitative labour practices involving low-paid workforces. Their use results in an escalating contribution of the tech sector to climate catastrophe through greenhouse gas emissions, [20] and environmental stress caused by e-waste being dumped in countries in Asia and Africa, particularly in impoverished local communities. The environmental cost, displacement of peoples, human and labour rights violations, and environmental racism that accompany the production, use and disposal of technology, are likely to increase dramatically over the medium to long term.

The entrenched interests of big tech, and the struggle to regulate

The complex alliance between the interests of states and the corporate tech sector underpins the multiple and interlinking policy and regulatory challenges that the evolving digital context presents. While the United States and the European Union, among others, have taken steps to regulate and tax big tech companies and platforms, the structural role that big tech firms play in multiple spaces and areas of service provision to states, and the dependency of markets, including national economies, on the corporate tech sector, suggest that the impact of this regulation is likely to be limited in curbing their influence and power. Nationally based big tech platforms with global footprints have also shown to be useful to states in contexts of armed conflict with respect to censorship and the control of information. In these respects, the regulators are effectively in compromised positions.

In the global South, there have been some fresh attempts by governments to create the enabling policy and regulatory frameworks for the new era of digitalisation and datafication. For example, the African Union has published a new data policy framework to try to harmonise disparate country regulations so that African countries can better benefit from the data economy and to explore methods of taxing platforms that have no legal presence in their jurisdictions. [21] There are also attempts to reinvigorate universal access funds, and support in a number of countries for community-centred connectivity initiatives, [22] including due to the work of APC. However, many countries in the global South lack the capacity to properly participate in and influence global governance and agenda-setting forums. This vulnerability means that they are largely subject to the regulatory and policy agendas set by developed economies and powerful corporate actors.

The interests of powerful tech corporations as well as states in what is being referred to as “universal meaningful connectivity” also carries new risks that efforts in working with communities to develop local access solutions based on the principles of network self-determination could be undermined. These include satellite connectivity enterprises by private sector actors already in a dominating position in the tech industry such as Starlink [23] and Amazon. Meanwhile, fresh questions of the human rights commitments of big tech platforms have been raised, including through the loss in advocacy gains in Twitter/X dissolving its Trust and Safety Council, ongoing concerns about the labour rights of gig workers, and Amazon being linked to the trafficking of workers in Saudi Arabia. [24]

A minimising of spaces for civil society to be heard

There is a gradual minimising of civil society interests in policy spaces. A symptom of this is what seems to be a weakening commitment to inclusive and multistakeholder governance, most obviously through attempts to sideline the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) in the process of forging a Global Digital Compact (GDC). This institutional destabilisation of the IGF has gone hand-in-hand with the apparent favouring of intergovernmental negotiations in the GDC process, the Summit of the Future, as well as other UN-related processes, rather than an acknowledgement of the need for a multistakeholder inclusive policy agenda on our digital future. Multilateral forums are becoming more difficult for civil society to access and impact. Civil society is increasingly facing barriers to the operationalisation of a multistakeholder approach and apparent attempts to weaken the few active multistakeholder processes that exist. An example of this is the recently created UN High-Level Advisory Board on Artificial Intelligence, which has been criticised for having “more representatives of companies [on the board] than organisations defending human rights.” [25] There is also a legitimisation of anti-rights groups at these forums, with some applying for legal recognition in different UN bodies in what seems to be an attempt to appropriate and disrupt progressive civil society spaces.

While there are some efforts to reactivate processes such as the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) and to reinvigorate the flagging targets of the SDGs, other important policy initiatives, such as NETmundial, lie largely dormant. These are ignored alongside the gains of the IGF as a collaborative space for co-learning, discussion and debate, with evidence of clear policy impacts in countries across the world. [26] There has been little apparent attempt to reinterpret the principles and vision of the WSIS to ensure that the lessons learned from years of multistakeholder cooperation feed into future processes of internet policy, internet governance and global digital cooperation – as a set of parameters for safeguarding multistakeholderism, transparency, inclusivity, dialogue and accountability. Instead, there is a sense that these lessons are being set aside in an effort to reset the policy agenda for the envisaged new social contract that shapes the digital future.

The hosting of events such as the IGF in countries where access for organisations is restricted, difficult or not viable – including Japan, where civil society actors had their visas denied, and the proposal to host the next IGF in Saudia Arabia – also weakens the capacity of forums for robust interactions from diverse perspectives. [27] While negotiations on the shape and content of the GDC will begin soon, no mechanisms have been established for the effective participation of civil society. Repeated assertions of the actors leading the process that it is a multistakeholder process have amounted to little more than token gestures.

A fragmentation of policy-making processes, and silo-ised civil society agendas

Outside forums such as the IGF, internet policy-making and agenda-setting spaces have become fragmented, with multiple initiatives and policy-setting processes co-existing. This makes it difficult for any single organisation to keep up with developments, to develop the expertise to participate robustly in each space, and to effect necessary change. Participation is further limited by the clampdown on civil society in many countries, throttling their ability to engage, including through new sector regulations stifling the flow of donor funding, new tax laws and limitations imposed on the transfer of funding for activities, and barriers to travel through visa processes that increasingly deny the freedom of movement of actors in the global South.

Perhaps in response to this fragmentation, and the diverse advocacy needs being confronted, civil society organisations sometimes develop overlapping and competing agendas, with a lack of alignment in often similar campaigns and advocacy objectives.

Despite a hyper-specialisation in some organisations that respond to specific technical needs in policy and regulatory advocacy, only moments of cross-organisational learning occur. There are also many new actors in the governance spaces we engage in, with only limited coordination between newer and more established organisations so that institutional experiences can be shared and passed on. The result is a weakened advocacy base from which activists can insist on change. These developments, which cannot be resolved in the short to medium term, have all undermined prospects for the global post-pandemic economic recovery and stability needed. They have eroded rights, and diminished the potential for cooperation around issues of shared concern, including climate change, a common digital future and the SDGs.

ASSUMPTIONS AND POLITICAL BELIEFS

Under the conditions outlined above, new efforts at organising are necessary to bring actors advocating for digital inclusion, democratic governance of digital technologies and digital and internet rights together, and to connect their concerns with the agendas of other social movements. Collaborative knowledge building and the sharing of experiences are needed to build the evidence base for coherent counter-narratives that are necessary for effective policy and rights advocacy and to influence agendas. Collective organising is needed to more effectively influence institutional processes, and to counteract intersectional rights violations in countries across the world. To start to redress worsening global inequalities, the robust participation of local communities in this organising is required, particularly those most excluded from digital opportunities, those most affected by a deterioration of rights and the [30] shrinking of the civil space, and those most vulnerable to climate change and environmental destruction and injustices.

Significant work is needed to counteract the environmental racism found across the global South, as well as the threats to environmental and land defenders opposed to state plans and the interests of big business. In a context where the rights of gender-diverse people and women are coming under renewed threat in many countries across the world, both online and offline, the digital resilience of gender justice actors, feminists and women human rights defenders also needs to be strengthened. This requires building supportive networks that serve as collective and personal resources for the advocacy work that is being done. As we have found in our work with community-centred connectivity networks, as well as in working with feminist groups across the world, it is only through such a holistic approach to building digital resilience that sustainable change can be achieved.

We believe that strengthening collective organising [28] towards building a transformational movement to advance digital inclusion and digital and internet rights is the best chance of ensuring that the internet strengthens social, political, cultural, economic and human development and enables the realisation of human rights. This is because systemic long-term change of this kind requires the building of collective power – people speaking not just as individuals, or through particular organisations, but with a powerful, collective voice. While movements are also often the most effective way for marginalised communities and groups to become visible and have their voices heard, they can create sustained change at levels that policy and legislation alone cannot achieve because they both create demand for change and hold powerful actors to account.

Collective power also challenges the status quo and the hegemony of government and corporate narratives and perspectives.

We understand a movement to be “an organised set of constituents pursuing a common political agenda of change through collective action” [29] that is distinguished by several characteristics. It has participants who are mobilised and collectivised in either a formal or informal way. It has a clear political agenda, and collective actions and activities built around the pursuit of the movement’s political goals through a variety of strategies. It also has clear internal or external targets for change. We believe that in the digital age, movement building has been transformed by the internet and digital technologies. Activism and collective organising happen seamlessly online and offline. We have learned from our work on feminist internet and movement building that movements are strongest when energy and ownership come from a multitude of spaces and actors. [30]

We recognise that organisations and collectives are often the sites from which movements are built, supported, serviced and governed. They are also the primary structures in or through which movement leaders, activists and members are organised, trained, capacitated, protected and energised to pursue the transformational agenda of movements. We also believe that networks, and particularly “movement networks”, have an important role to play in strengthening collective organising and action, because they connect actors and resources in order to create greater impact than an individual or organisation can achieve on its own.

APC is particularly well placed to play a pivotal role in the strengthening of collective organising towards building a transformational movement to advance digital inclusion and digital and internet rights for a number of reasons. We have credibility and legitimacy based on our longstanding contributions to digital inclusion and digital and internet rights, and have made a consistent contribution to shaping and broadening regional and global internet governance processes over the last 25 years.

We have a diverse membership rooted in the global South, which, together with our projects and programmes, have played a significant and consistent role in making the voices and perspectives of marginalised communities heard in the context of digital inclusion and digital and internet rights issues and processes. We also have strong experience working at the intersections of multiple social movements, and as a convener connecting activists and building bridges across regions, issues and agendas and linking the local with the global.

Because APC’s membership is a microcosm of broader digital inclusion and digital and internet rights organising, we can most effectively play this movement-building role through and with our network of staff, associates, members and partners, in collaboration with close allies that are part of the broader digital inclusion and digital and internet rights field. And as our work on feminist internet and movement building shows, over time the network becomes more self-sustaining with strong shared ownership of common agendas and collective leadership to advance network priorities. [31]

OUR VISION AND MISSION

Our vision is for all people, particularly the marginalised, to use and shape the internet and digital technologies to create a just and sustainable world.

Our mission is to strengthen collective organising towards building a transformative movement to ensure that the internet and digital technologies enable social, gender and environmental justice for all people.

NETWORK- AND MOVEMENT-BUILDING STRATEGIES

The purpose of our network- and movement-building strategies is to achieve APC’s mission. They support and strengthen collective organising among and within the network of APC members, associates, partners and allied human and digital rights, feminist and environmental justice defenders and organisations. We do this through:

- Conducting new research and deepening the use of existing research to build knowledge and create counter-narratives around new and emerging issues and trends that affect the context in which we are organising.

- Convening and connecting diverse actors and constituencies within the network to build and strengthen connections and common agendas within and across diversities of issues and regions.

- Capacity building and institutional strengthening within the network to strengthen the ability to act collectively on common agendas.

- Policy advocacy and mobilisation within the network to amplify the voices from marginalised communities, put pressure on stakeholders, and advocate for changes in norms, policies, standards and practices, particularly related to governance of the internet and digital technologies.

- Grantmaking/subgranting to the network to resource their work, strengthen relationships in the network, and support them to engage in building and acting collectively on shared agendas.

- Strategic communications to amplify the voices and perspectives of the network.

LONG-TERM OUTCOMES

By 2027, we are committed to building a network of members, partners and allied human and digital rights, feminist and environmental justice defenders and organisations that:

- Builds and strengthens common agendas across issues, movements and geographies to promote digital inclusion, digital and internet rights, a feminist internet, and environmentally just digital policies and practices.

- Amplifies our voices and perspectives to position human rights and gender and environmental justice centrally in digital inclusion and digital rights discourses and to counter anti-rights discourses.

- Acts collectively to shape digital norms, policies, standards and processes that are democratic and rights-respecting to ensure that the internet and digital technologies are governed as a global public good.

- Increases our collective capacity for holistic safety and care and digital resilience.

In order for APC to enable and support the contributions of the network to these four long-term outcomes, we are committed to ensuring that:

- APC has a shared vision and purpose, and has the capacity, skills and financial resources to deliver on its mission in a working environment in which all members and staff can learn, grow and thrive.

IMMEDIATE OUTCOMES

The more immediate changes to which we will contribute during 2024-2027 or the “preconditions” for the longer-term outcomes are set out below.

Outcome 1: Common agendas are built and strengthened across issues, movements and geographies to promote digital inclusion, digital and internet rights, a feminist internet, and environmentally just digital policies and practices.

Rationale

The internet and digital technologies are enablers of human rights, social, gender and environmental justice, and development. However, this potential is being undermined by the rapid and unchecked pace of digitalisation and the datafication of economies and societies, including by the impact this is having on the environment. Online rights violations have multiplied, the power of states to surveil and control has been strengthened, and the big tech sector is in an increasingly advantageous position to influence and control policy deliberations and to resist change. At the same time, unconnected and already marginalised communities face further marginalisation in the absence of any meaningful internet access for socioeconomic and political participation.

In an increasingly polarised geopolitical landscape, the prospects of realising shared objectives and targets such as the SDGs and on climate action are diminishing. Civil society actors are also facing new forms of oppression with the rise of authoritarian states and a strengthening of reactionary politics. Particular threats are being faced by feminist and LGBTQIA+ communities, while attacks on environmental and land defenders are escalating as pressure is placed on the Earth resources of countries in the global South. This is making rights-based and environmental justice advocacy difficult in many countries. Meanwhile, civil society organising for digital inclusion and digital and internet rights is fragmented, characterised by a large number of new actors, hyper-specialisation, diverse and overlapping causes, and an increasing sense of the silo-isation of many advocacy efforts.

In this context, there is a need to strengthen collective organising towards building a powerful movement to advance digital inclusion, digital and internet rights, and a feminist internet. This needs to be built across movements to support all social justice actors facing digital harms, with a specific focus on feminist and environmental justice movements. Regional differences in the experiences of digital harms also makes it important to work and learn across regions to deepen our advocacy impact. The voices of the most excluded and discriminated against – including low-income communities, women and gender-diverse people, local communities most immediately impacted by climate change, and Indigenous peoples facing environmental destruction – need to be strengthened in regional and global policy-making and human rights forums.

Immediate outcomes

- APC members and partners strengthen community-centred connectivity agendas by awareness raising and providing effective support, capacity development and tools to communities that need viable community-centred connectivity, and enabling them to utilise local services and digital technologies to meet expressed community needs.

- APC members and partners strengthen their connections, explore shared concerns and create and strengthen common agendas for advancing digital rights, a feminist internet and environmentally just digital policies and practices.

Outcome 2: Amplified voices and perspectives position human rights and gender and environmental justice centrally in digital inclusion and rights discourses and counter anti-rights discourses.

Rationale

New forms of rights violations are occurring across the globe, both with the rise of authoritarianism and with big tech now mediating many of our human rights online. Anti-rights discourses have proliferated on the internet, pushing back against the rights gains over the past years. These include resurfacing discriminations against women and the LGBTQIA+ community, and the often violent silencing of women and gender-diverse peoples. At the same time, powerful interests in the extractive industries hold climate action at bay, and use disinformation efficiently to influence policy making and public opinion. Another form of “silencing” is the failure to adequately consider the significant environmental impacts of digital technologies, including the impact on the local communities most affected by the extraction of minerals used to produce them.

Discourse delimits what gets discussed and talked about, and sets the boundaries of what policy responds to, as well as the language used in policy. This has important repercussions for what gets acted on, and in what way. By challenging anti-rights discourses, or reframing discourses that do not take specific rights and environmental concerns into consideration, marginalised voices and issues that are fundamental to social, gender and environmental justice can begin to receive proper attention from policy makers and legislators, as well as, ultimately, the private sector.

Rights violations and the impacts of technology on the environment – whether due to extractive mining, the hosting of server farms, or the dumping of e-waste – are being experienced in different ways in countries in the global South, as is the rapid pace of digitalisation and datafication of societies. Collective knowledge building and learning is needed to understand the nuances, while both feminist and environmental justice discourses need to be mainstreamed in digital rights deliberations to strengthen their articulation in advocacy and policy processes. The collective voices of civil society actors need to be amplified to push back against the growing influence of anti-rights narratives.

Immediate outcomes

- APC members and partners have greater capacity to counter dis/misinformation.

- APC members and partners collectively create, strengthen and share knowledge to influence policy discourse.

- APC and partners co-create alternatives and counter-narratives which centre digital inclusion and digital and internet rights and their intersections with environmental justice issues.

- APC members’ and partners’ intersectional feminist voices from the global South contribute to centring feminist perspectives in discourses on technology, towards realising a feminist internet.

Outcome 3: Collective action shapes digital norms, policies, standards and processes that are democratic and rights-respecting to ensure that the internet and digital technologies are governed as a global public good.

Rationale

The silo-isation and fragmentation of digital and internet rights work across regions and issues is deepening the difficulty of responding to a rapidly changing and uncertain context. The multilateral spaces for influencing agendas are themselves fragmented and becoming more difficult to access and impact for civil society, with powerful corporate stakeholders and governments dominating discussions. Many civil society organisations also lack the capacity and expertise to respond robustly in the multiple policy and governance forums that exist, often on specialised topics. The result is that the voices and perspectives of civil society and the most marginalised are being sidelined in practice in global policy discussions and forums, where there appears to be a flagging commitment to multistakeholder and inclusive deliberations.

With the threat of deepening global inequalities and the further marginalisation of low-income and remote communities, the participation of these communities in the deliberations about the governance of the internet and other digital technologies is more necessary than ever before. Civil society actors working close to the ground need to be supported in their efforts to advocate for people-centred internet governance policies and processes, including by drawing on the skills and knowledge of the network. Collective action that draws on local and national experiences is necessary to influence processes related to the governance of the internet and other digital technologies, and to bring about policy change at the regional and global levels.

Immediate outcomes

- APC members and partners provide knowledge and expert support to increase awareness of community-centred connectivity among communities and policy makers and to transform policy and regulation so that it enables community-centred connectivity in the global South.

- APC members and partners strategise together and collectively mobilise to engage in and influence priority national, regional and global processes to integrate human rights and environmentally just digital policies and practices.

- APC leverages our access to regional and global processes on policies, norms and standards to ensure that they include the voices and perspectives of marginalised communities and are democratic, open, transparent and accountable.

- APC members and partners increase the integration of rights-based perspectives and agendas of women and people of diverse sexualities and genders into digital policies, norms and standards.

Outcome 4: Greater collective capacity for holistic safety and care and digital resilience.

Rationale

All people, but particularly the most vulnerable and most threatened – including low-income communities, women and gender-diverse people, and local communities at the forefront of environmental destruction and most immediately impacted by climate change – need to be able to use the internet and digital technologies in a way that is secure, safe, and free from violence, intimidation and harassment. In the current context of intensified attacks both offline and online on Indigenous communities opposing environmental destruction, as well as on women and gender-diverse people, specific attention needs to be paid to support the digital resilience of environmental and land defenders and gender justice actors and feminists. Collective solidarity and action can play a powerful role in responding to defenders at risk. This support, however, needs to be articulated in a participatory way that is meaningful to their specific and nuanced struggles, and that questions power structures perpetuating intersectional inequalities. The support should take into account their life-worlds, experiences and needs, and enable their personal and political autonomy and agency.

Immediate outcomes

- APC and our partners have a shared understanding of the online and offline threats we are facing and develop collective strategies of holistic safety and care to address them.

- APC and our partners have greater capacity to create and strengthen our digital infrastructure.

- APC and our partners collectively mobilise in solidarity to provide support to defenders at risk.

- Feminist activists and gender non-conforming and queer communities have greater capacity to engage with the internet and other digital technologies with care, agency, curiosity, playfulness and safety.

Outcome 5: APC has a shared vision and purpose, and has the capacity, skills and financial resources to deliver on its mission in a working environment in which all members and staff can learn, grow and thrive.

Rationale

To strengthen collective organising we need to foreground this aspect of our work, ensuring that the different elements of network- and movement-building strategies found across projects and programmes function in a coordinated way so that we achieve the outcomes of this strategic plan. We need to strengthen internal knowledge building and sharing and coordination in project planning, and develop shared impact indicators across all projects and programmes. A culture of learning and collective care needs to be further nurtured among members and staff in order to support the advocacy outcomes, to enable and support members and partners so that we can collectively contribute to the above outcomes, and develop and sustain a sense of common purpose that allows members and staff to grow and thrive in their activist work. We need to continually build our internal commitment to living our values, in how we organise and work together.

Immediate outcomes

- APC members and staff have greater knowledge of and stronger connections with each other.

- APC members and staff have greater capacity to work together strategically and operationally based on a shared vision and purpose.

- APC’s knowledge management, planning, and monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) systems support collective learning and ongoing prioritisation of our work for deeper impact.

- APC members and staff have a greater shared understanding of care and collectively build organisational policies and practices that support our collective well-being, resilience and sustainability.

- APC has a diverse and sustainable funding base.

[1] https://feministinternet.org/en/page/about

[2] The Local Networks (LocNet) initiative, which started in 2017, is a collective effort led by APC and Rhizomatica in partnership with grassroots communities and support organisations in Africa, Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean.

[3] https://www.apc.org/about/history/enabling-civil-society-policy-making

[4] This text is from APC’s input in 2000 to the UN’s High-Level Panel on ICT for Development. This quote is included in “Involving civil society in ICT policy”, APC, 2003. https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/InvolvingCivilSociety_EN.pdf

[5] It is important to understand the difference between the “human rights-based approach” and defending human rights. The human rights-based approach’s roots are in the global South (expressed in 1986 in the UN General Assembly resolution on the right to development), and in the social justice critique of individual civil and political rights that emerged towards the end of the cold war. APC’s work with human rights has always been about more than just individual rights, or digital rights..

[6] “Involving civil society in ICT policy”, APC, 2003, contains positions on the WSIS from APC regions and the Women’s Networking Support Programme. https://www.apc.org/en/pubs/involving-civil-society-ict-policy-world-summit-information-society

[7] https://feministinternet.org

[8] Luca Belli defines network self-determination as “the right to freely associate in order to define, in a democratic fashion, the design, development and management of network infrastructure as a common good, so that all individuals can freely seek, impart and receive information and innovation.” Building Good Digital Sovereignty through Digital Public Infrastructures and Digital Commons in India and Brazil | ThinkTwenty (T20) India 2023 - Official Engagement Group of G20 (t20ind.org)

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_North_and_Global_South

[11] A New Social Contract for a New Era - United Nations Sustainable Development

[12] Advocacy in times of TRIPS waiver | Global Information Society Watch (giswatch.org)

[13] WPSR 2023 Chapter 1.pdf (un.org)

[15] Ibid.

[18] Including but not limited to Palestine, Jordan and Lebanon (Algorithmic Anxieties & Feminist Futures in MENA | GenderIT.org), Tigray in the north of Ethiopia (Tigray: Life Beneath the Sealed Skies | GenderIT.org), and countries such as India, Nigeria, Uganda and, more recently, Kenya.

[23] Starlink and Inequality - Many Possibilities

[24] Revealed: Amazon linked to trafficking of workers in Saudi Arabia | Amazon | The Guardian

[25] Derechos Digitales on Tumblr

[28]. This framing draws on the work of Srilatha Batliwala, a feminist activist and scholar who has worked with large-scale grassroots women’s movements (https://issuu.com/awid/docs/changingtheir-world-2nd-ed-eng?e=2350791/3186048), as well as the perspectives of APC staff.

[29] https://issuu.com/awid/docs/changing-their-world-2nd-ed-eng?e=2350791/3186048

[30] Evaluation of the APC Women’s Rights Programme’s work on feminist movement building in the digital age. https://genderit.org/sites/default/files/mfievaluation2020-brief4networks_september_2020.pdf

[31] Ibid.

Read APC's previous strategic plan for the period 2020-2023 in full here (HTML) or here (PDF).