For the sixth edition of our spectrum series, we are sharing the story of Adriana Labardini Inzunza's journey to the remote community of Santiago Nuyoó, Oaxaca, with Mexico's under-minister of information and communication technology (ICT), Salma Jalife, Rhizomatica's Peter Bloom, and Elisa Castillo of Telecomunicaciones Indígenas Comunitarias A.C. Adriana is an independent public interest lawyer and consumer rights expert, who works with APC member Rhizomatica as an advisor. She has consistently worked to bridge the digital divide and promote rural and indigenous connectivity and media.

During a two-day trip to the area, Adriana and her companions gained further insight into the specific challenges of rural connectivity and the remarkable power of community-owned networks to connect the unconnected and empower indigenous communities. The story offers a very human look at the impacts of building sustainable technological and community-led solutions to connectivity challenges. As Salma Jalife aptly noted in the wake of the trip, ultimately, “It is all about the people, not the technology."

In September 2018, Salma Jalife, then in charge of International Affairs at Corporación Universitaria para el Desarrollo de Internet A.C. (CUDI), had been asking Rhizomatica for multiple months to show her some of the 14 communities that manage their own mobile networks in the mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico. Through their own non-profit organisation, Telecomunicaciones Indígenas Comunitarias A.C. (TIC A.C.), with the technological, organisational and legal support of Rhizomatica and Redes A.C., these communities were granted a spectrum licence for the deployment of wireless networks for indigenous use in rural locations of five states of Mexico – Oaxaca, Guerrero, Puebla, Veracruz and Chiapas – as well as a blanket licence to provide telecommunications and broadcast services in those areas, subject to spectrum assignment.

Salma did not want to wait any longer. She wanted to see for herself this unprecedented, emblematic model of self-sustainable community wireless networks, enabled by the combination of a new Telecom Act and the allocation of spectrum for social-indigenous use by the regulatory agency, Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT), as well as the innovative and equitable network model developed by Rhizomatica and Redes A.C. founders Peter Bloom, Erick Huerta and their team.

It was 28 September. Salma had recently been nominated to become the new under-minister of ICT, as announced by the minister-to-be Javier Jiménez Espriú, once president-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador took office on 1 December. She only had two days for the journey and yet, she wanted to visit the most remote rural community that is part of TIC A.C. networks, even though it meant driving five hours at dawn, staying overnight and driving back to Oaxaca the next day for her flight to Mexico City. We both wanted to go to the Mixteca Alta mountains to talk to the local people and understand their chosen internet technology and its management as well as the community's needs, priorities and engagement in operating the network. We hoped to understand not only the technical challenges for the access network, but also for backhaul. And so, we flew to Oaxaca, sleeping bags in hand, to stay in Nuyoó overnight and spend more time talking with the community members.

Worried about us getting stuck on a dirt road during rainy season, Peter Bloom kindly drove Salma and I to Nuyoó in the TIC A.C. truck. As the founder of Rhizomatica and an experienced activist using ICT to protect human rights in Africa, he was able to explain every piece of infrastructure in the area to us. Joining us was Elisa Castillo, TIC A.C.’s community manager and expert on community organisation, who plays a key part in TIC A.C.’s success.

The first 100 kilometres of the highway was perfectly paved and wide, taking us past beautiful colonial cities that reveal the legacy of the Dominican missions. One example was Santo Domingo de Yanhuitlán. Santo Domingo is more urban than rural. You can tell there is electrical power and telephone, television and internet services. More than one shop was offering “Wi-Fi cards”, which refers to pre-paid internet access at downtown internet cafés. The messy installation of aerial cables was visible throughout the town.

We continued northwest for a while. Santiago Nuyoó is a Mixtec municipality within Tlaxiaco district, a large city by regional standards. Nuyoó is 248 kilometres away from Oaxaca, nestled in the Mixteca mountain range. It has a population of approximately 1,996 people. The municipality encompasses 19 communities besides Nuyoó, including Yucunino at the top of the mountain, Yucubey and Loma Bonita. Most are covered by the three antennas that compose the community’s cellular network. A map of the route to Santiago Nuyoó can be found here.

Nuyoó is a beautiful place, with rich soil and abundant water, trees and wildlife. Its blue skies and misty mornings belie a surprising reality: it is one of the indigenous municipalities classified by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) as being extremely impoverished.

As we left Tlaxiaco behind, we noted that along the narrow highway, there were poles with yellow signs that read: “This is optical fibre, not copper, property of Telmex.” All this roadside fibre accompanied us for many kilometres as we drove away from Tlaxiaco, hanging from telco poles in some areas but, at other times, from Comisión Federal de Electricidad’s (CFE) medium tension system. Salma, Peter and I kept saying that it would be great if these communities of the area could access this transport fibre so that their data traffic could be backhauled or transported more easily. This is the backbone of Telmex, and since IFT passed its asymmetric regulation for Telmex and Telcel mandating access to both passive infrastructure and leased lines (fibre and copper) of the incumbent, it is not affordable for communities to use such assets. The public tenders are designed for commercial operators, not for community-owned networks with smaller economies of scale. This, unfortunately, leaves underutilised fibre capacity in the hands of a small few. A fibre-sharing policy for non-profit community networks would prove very useful. Similarly, mandating spectrum sharing in remote rural areas would be a highly effective way to enhance digital inclusion and relieve large operators who pay annual fees for nationwide spectrum licences, whether they are using them or not. Furthermore, as we could all attest when our own phones lost connectivity after leaving Tlaxiaco, none of the commercial operators use their licensed spectrum in these very remote locations, as it is not profitable.

Sharing fibre and spectrum in the Mixteca heights would therefore prove beneficial for all parties; the spectrum holder could be exempted from paying annual fees for the spectrum they share with a given community network licensee, this network in turn would actually provide internet service to its users, and the state would be able to better meet its obligation to provide universal service to all unserved communities.

It is important to emphasise that the same holds true for the new Red Compartida, which is a wholesale network building an LTE network on the 700 MHz band to offer capacity to mobile virtual network operators (MVNOs) and wireless operators. Although Altán, the licensee and network owner, received all 90 MHz bandwidth on a nationwide basis, it is only required to provide coverage to 92.2% of the total population of Mexico, and it has a choice of which cities and towns it connects. Obviously, in order to maximise profit, it will leave out thousands of small rural communities where the other 8% of people live.

Interestingly, many of the 12 million indigenous people of Mexico still live in their original territories. Many of these will not be served by Altán’s network, and yet, the company will hold the national spectrum licence for 20 years.

Shouldn’t a “use it or share it or lose it” rule apply to bridge the digital divide? It is crucial that this very valuable APT 700 band (a coverage band) among others be used efficiently in isolated rural communities where the risk of interference is very, very low and the potential benefits to these impoverished communities are huge.

After a five-hour drive, we finally arrived in Yucunino, the highest altitude community within Nuyoó. Here, we met with Teresa Sarabia, the mayor of Nuyoó and a true warrior in defence of her people, along with local authorities from Yucunino. These local leaders all feel proud of having their own cellular network, which allows them to keep in touch over the phone, especially since villagers are scattered among 20 villages and visiting a relative from one hill to another can take a while on foot. Every year, the community repairs the dirt roads after the rainy season.

We also saw that, in Yucunino, there is a México Conectado hotspot. This is a federal government effort to connect rural villages using, in most cases, satellite (VSAT) technology. We saw the equipment, and I tried to connect to the internet through it. The first thing I was told was to stand only four feet away from the router so that I could log on. The signal was very weak, and all the villagers would have had to come upstairs to the city hall office should they want to log on.

After a while, I was able to send a WhatsApp text. Needless to say, my own 4G phone was useless there as my service provider coverage ended as we hit Tlaxiaco. But amazingly, Teresa invited me to subscribe to the TIC A.C. network that appeared on my smartphone screen as an “available signal”. For USD 2 a month, I was offered access to unlimited calls and messages within the TIC A.C. network. All you have to do is subscribe at the office in Nuyoó and they log you on. You can also make off-net calls to the rest of the country and to the United States for rates that range from one to four cents per minute. These latter services are not provided by TIC A.C. but by a voice over internet protocol (VoIP) service provider that TIC A.C. has integrated into its system.

The goal is to eventually deploy a 4G network, which not only costs significantly less than a 2G antenna, but is also data-enabled. In order to use 4G, TIC A.C. would need both more spectrum in a band suitable for rural coverage and access to backhaul through a combination of fibre, where available, and microwave links.

While these innovative open and sharing models, which provide the necessary inputs for accessing community networks, have shown to be successful, they require greater access to backhaul and transport networks to be truly efficient.

The other technology that can be used as backhaul is satellite. The Mexican state is entitled to satellite capacity on every Mexican satellite and even on foreign satellites with landing rights in Mexico. In an unprecedented and wise move, the former administration, through the Ministry of Communications (SCT), executed an agreement with TIC A.C. to allow for the latter to use a small part of this capacity as backhaul for its sites. These kind of shared access arrangements, in my opinion, are extremely empowering and a healthier way for governments to support community-owned networks.

But, are there substitute services in Nuyoó for those of TIC A.C.? Honestly, no.

In Yucunino, there is a small convenience store selling soft drinks and snacks, which has a Telmex Multifón telephone booth that allows for residents to make or receive calls with pre-paid cards. Rates range from 1 peso/minute (USD 5 cents) for domestic calls to a landline number or 1.50 pesos/minute to a mobile number, to 5 pesos/minute (USD 25 cents) for a call to the US or Canada. All of these rates are significantly higher than those of TIC A.C., and therefore unaffordable for a sustainability economy like those we see in very economically disadvantaged areas.

Government initiatives to provide telecommunications services to rural end-users in public facilities such as schools and hospitals are necessary to facilitate e-education and e-health as part of a universal digital government programme. High-speed broadband should be a priority for remote diagnosis or multimedia education platforms, as opposed to the very erratic quality of service available for those purposes in some of the remote locations in Mexico.

Wi-Fi hotspots in other public spaces of rural communities for mobile phone users, however, have had major technical problems and have not proven sustainable for the federal government over the years. Technical maintenance, network monitoring and customer service management have been challenging. The current ICT under-minister, Salma Jalife, will have to conduct an in-depth cost-benefit analysis before the ministry embarks on a fourth generation of universal service programmes during the new six-year term of the federal government. There are many lessons to learn from all those top-down models.

While on our way to see the tower site up in the Yucunino mountain, we talked for a while with the local people. They shared some stories about how they use their phones to keep in touch with migrant relatives or local friends, to find out the price of produce in the Tlaxiaco market, or to call the clinic when an ambulance is needed. There are approximately 600 subscribers in Nuyoó already.

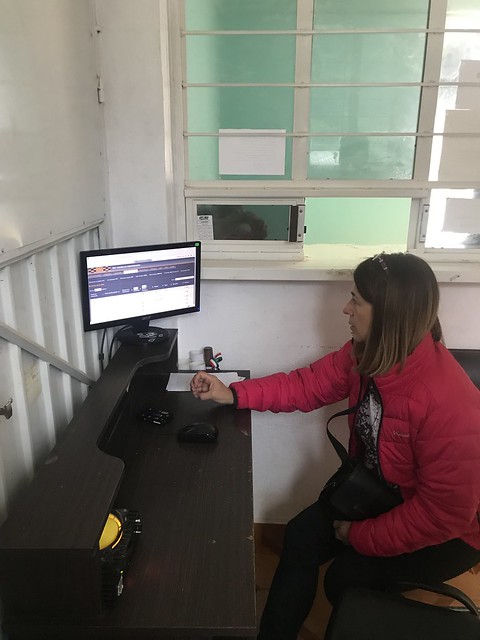

Once at the site, we observed how and where the radio bases are installed and operated through open source software designed by Rhizomatica. The network users are managed through a graphical interface software. Javier, 21, a high school graduate, is the network manager. He was trained by TIC A.C. to operate the interface from a desktop computer in Santiago Nuyoó´s community telephony office. Javier is proud to be the manager – he enjoys his job and wants to keep learning about technology.

The community authorities decide, according to their indigenous self-government rules, if they want the service, how they will contribute to the capital expenditure of around USD 9,000 per tower and base station, who will get trained to manage it, etc. The beauty of the model is that with the USD 2 monthly fee per subscriber, the network is able to pay TIC A.C. for the service, contribute to an emergency fund and keep a large portion of the subscriber fees within the community for future investment in local projects. It is important to have at least 100 subscribers per community to make the operation costs affordable and the network sustainable.

After a long morning visiting the sites, we finally headed downhill to downtown Santiago Nuyoó where community members hosted a delicious lunch and showed us the town, TIC A.C. offices and municipal city hall, where we would hold an evening meeting with the villagers.

When I first got to the city hall building, I noticed several rusty satellite dishes on the rooftop, of all sorts and sizes. Out of curiosity, I asked if I could go up there and see what they were. To my surprise, it was like a cemetery of different generations of federal government dishes belonging to various universal service programmes that went extinct after the six years of the corresponding federal administration. E-Mexico, C-SIC and México Conectado (this one was still alive in September at least, but I guess not for long) satellite dishes for satellite telephony were just sitting there rotting. I was also told that a forgotten tower belonged to a failed pilot programme started by Telecomunicaciones de México in partnership with Banorte, a Mexican bank, to bring banking services to the community using cellular phones. These phones could not be used for any other purposes than banking. This model, however, is not suitable for the context at all, as it gives Banorte the ability to charge outrageous fees for each money transfer, encouraging unsustainable consumption from people who make less than USD 3 a day. Unsurprisingly, the infrastructure and pilot project were abandoned.

It is important to understand which kind of ICT projects and models may trigger sustainable development goals and honour the community’s principles, priorities and preferences. Selling things, including banking services, not to access capital but to have locals consume unnecessarily and become indebted for life, will not help people get out of poverty. I do understand that the ability to pay for things such as your power bill through mobile payments can prove very useful, considering it’s normally necessary to travel three hours to Tlaxiaco to do this, and e-payments can only be made in Nuyoó at the Telecomm office four days a week. The office, moreover, often runs out of cash.

There needs to be a much more efficient method for villagers to pay bills and exchange goods. One such method could be an IT app or a ledger, a simple blockchain process if you will, but I do not see the government doing that. This issue could be solved, however, through disruptive technologies, open source software and community organisation combined with proper training and capacity-building programmes.

The government does play a major role in providing other kinds of access: roads, public schools, learning material, good teachers, water, backhaul and fibre nodes, IXP facilities, spectrum access, health services, etc. Alternatively, the government can transfer the resources and jurisdiction to these communities in order to build their own roads, networks, markets, schools, water plants and other basic infrastructure, and charge for it. As Teresa told Salma, we only need building materials to renovate the school; we all know how to build.

In a community with such a deficit of public services, a wireless network is critical to access information, interact with the state and federal government, help citizens insert themselves in the local economy, receive emergency alerts when natural disasters are about to occur and in their aftermath, communicate among themselves and have access to other fundamental services such as education.

Nuyoó, believe it or not, has no broadcast TV signals at all. Ironically, the only formerly available public TV channel is no longer broadcast there because of the analogue switch-off; it could not afford to go digital, and commercial TV has no business incentives to invest in a low-power transmitter for a community in extreme poverty. Affordable and sustainable telecommunications and broadband infrastructure are therefore even more critical resources to access information, another fundamental right, and to fight isolation and poverty.

Spectrum is undoubtedly a valuable public resource, but it should not be a cash cow for governments with no regard for its actual potential as an enabler of development. Yes, in the context of large cities, amid the data economy and still-blurry 5G revolution in global economies, it is an invaluable resource for commercial operators to generate billions in revenues, where demand for data is exponentially increasing and scarcity is more evident. In remote rural areas, however, such a reality does not exist; spectrum is underutilised and the risk of interference (which should be the primary concern of regulation and licensing regimes) is non-existent. Thus, promoting spectrum use, whether on a primary or secondary title basis, is key to fostering inclusion, efficiency, technological entrepreneurship and the sustainable development of these economies.

With big smiles on our faces and a renewed sense of responsibility and understanding, we left Santiago Nuyoó on Sunday, but not without first visiting the Sunday market where people from all 20 communities gather to exchange their crops. We couldn't help but remark upon the strong spirit of the community and the great warmth and generosity the locals extend toward visitors. I dare say that for Salma, and myself, too, Nuyoó was an enlightening experience, one that gave us a more well-rounded perspective that will be extremely helpful when drafting public policy, designing sustainable development projects or speaking about human rights, technology-driven communities and digital inclusion. I only wish that more government officials would leave their big city desks where they make universal service decisions, as Salma did, to listen to and see the real world of indigenous communities.

The people of Nuyoó are proudly but humbly becoming role models for other communities in Mexico and abroad. I recently learned that mayor Teresa Sarabia was visited by two indigenous chiefs from the region: Lauro Arariwa, representing the Federation of Indigenous Organisations of Azuay in Ecuador, and Wilman Tumbo Chepe, governor of the Pueblo Nuevo reservation of Cauca, Colombia. They are pictured here with her.

On 11 December, Salma Jalife made her first public appearance as under-minister in front of Commissioner Estavillo from the IFT, ICT industry associations, academics, technology vendors, broadcasting associations and NGOs working on connectivity, inclusion and related public interest causes. She publicly acknowledged Rhizomatica’s efforts and initiative and shared with the audience how her experience in Santiago Nuyoó helped her to better understand the needs of rural communities and the challenges and opportunities to tackle social problems in a disruptive manner. “It is all about the people, not the technology,” she remarked.

On behalf of Santiago Nuyoó and Rhizomatica, we thank Salma Jalife for her visit and her interest in making change happen.

See a slideshow with a list of images from this trip:

Learn more about Rhizomatica's work here and view the Flickr album of the Santiago Nuyoó trip here.

Read the rest of the "What's new on the spectrum?" series, featuring interviews with Carlos Afonso of Nupef, Peter Bloom of Rhizomatica, internet access specialist Mike Jensen, Senior Mozilla Fellow Steve Song with Carlos Rey-Moreno of APC, and Karla Velasco Ramos and Erick Huerta of Redes A.C.