We talk about the transformation of communications all the time. I sometimes think we overdo it, conflating the transformation of communications with that of society. Sometimes, though, we forget just how much transformation there has been in our communications world.

I’ve been reflecting on this while reading a new review of Africa’s experience: Africa 2.0 by Russell Southwood, longstanding editor of the online newsletter Balancing Act which reports on ICTs across the continent.

The past matters

We’re where we are because of where we’ve been. Policies that were needed to change things yesterday leave lasting legacies. They influence the way things work today and that, in turn, constrains the options we have for tomorrow. This is particularly true where technologies and impacts are changing fast.

Southwood’s book describes the changes he’s reported on these 20 years. It’s a reminder of how bleak Africa’s communications landscape was a generation back; of key stages in the evolution of today’s environment; of the influence of governance (often restrictive, sometimes corrupt, sometimes dynamic), investment (often non-African but also African), services that hit or missed the needs of African communities, successive waves of African entrepreneurs and the challenges they faced.

So let’s look back a little at what was, at how it changed, and at what understanding what has changed implies for now and next.

Remembering the 1990s (and before)

When I first worked on communications policy (over 30 years ago), telecoms in Africa were very few and far between. The Maitland Commission had noted in the mid-1980s that, in some countries, there was just one phone per thousand people. One country’s universal service obligation at the time, as I recall, was to provide a telephone within a day’s walk of every citizen.

Most customers were governments and businesses; few private citizens had phones and those that wanted them had long to wait. Infrastructure was sparse, international communications expensive and still routed along colonial lines, state monopoly telecommunications businesses short of investment.

It’s important always to relate communications contexts to their impact on real lives: on social interaction, economic potential, cultural development, patterns of migration, response to crises.

The absence of communications infrastructure severely constrained the lives of citizens and scope for enterprise, especially in rural areas. High costs and poor quality made it difficult for new businesses to become established in domestic markets and established ones to compete internationally. Migration dislocated families more thoroughly and made it harder to seek help in times of crisis, domestic or collective.

What changed things?

I’d sort the changes that Southwood describes into five categories: concerned with governance, technology, services, infrastructure and behaviour. There’s no single change in any of these contexts but a trajectory across them all – a trejectory that starts slowly, accelerates and changes as technology becomes more sophisticated; that is uneven in its impact on individuals and societies. Here’s what I mean.

Governance

At the start of the story – in the ’90s and the early years this century – the biggest issue was seen (at least by international businesses and donors) as being governance. Old ways of doing things, and those with power over them, prevented progress.

European telecoms was radically transformed from the mid-1980s as state businesses were privatised, markets liberalised and the competition this unleashed was regulated to reduce the market power of vested and protect consumer interests.

That experience was gradually extended across Africa from the mid-’90s, with the backing of big donors like the World Bank – though often fiercely resisted by established telecoms monopolies. It brought in new investment, from international businesses, but that was concentrated in Africa not on landlines but on what was then the (relatively) new technology of mobile.

Technology

Changes in governance established a different context – a different ‘playing field’, as often called – into which new mobile networks entered. This new mode of communications was also, sometimes, resisted fiercely by vested interests. Southwood recounts the tales. State telcos continued to play parts in mobile markets, but governments usually also enabled competition to arise, first for licences and then between new licensees.

And mobile made a massive difference to markets. It could be deployed more rapidly and cheaply than could landlines, not least in rural areas, and it released unexpected waves of previously untapped demand. New mobile networks found they met in months the targets for subscribers they’d expected would take years. Fixed phones fell out of fashion gradually in Europe, but in most of Africa they were bypassed by mobile.

There was a time when many in the ICT for Development (ICT4D) community disparaged mobile phones as insufficient for development or personal need, as lacking in comparison with landlines. That time has gone, though investment in physical infrastructure remains critical to enabling mobile networks to achieve their most.

Services

What drove that mobile usage, first and foremost, was the opportunity it gave to make life easier and better. Research I worked on in the first years of the century showed up the key priorities for early users: social contact, especially with distant family members; getting advice or information (e.g. on health problems) and financial help without delay in times of need; reducing the cost of unnecessary travel, and feeling safer when out and about.

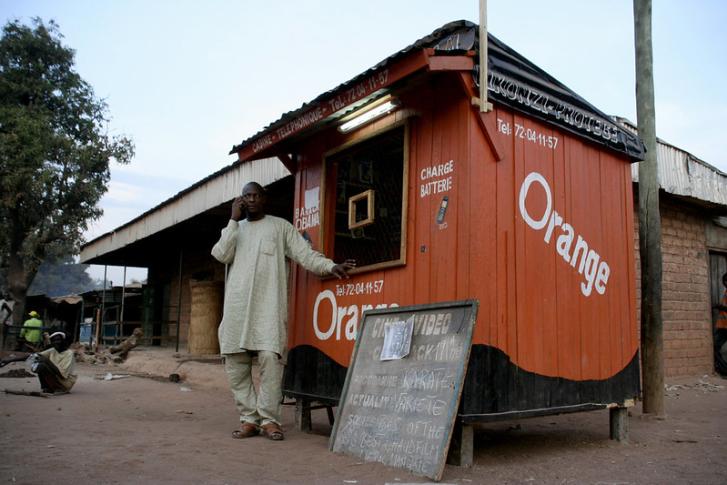

Mobile phones met straightforward needs like these effectively. They could be borrowed rather than owned; access to them could be made available commercially, by small-scale businesses, as well as public kiosks.

And on those mobile platforms, other services could be made available, particularly as the capabilities of networks and handsets grew. International development agencies saw this as opportunity, sponsoring online information services that sometimes worked and sometimes didn’t (because they focused more on agencies’ requirements than on users’).

In Kenya first, and then more slowly elsewhere, mobile money transfers proved valuable to telcos and valued by customers. Internet access became attractive, particularly to younger and more educated groups, initially through commercial cybercafes (more successful than agency-sponsored telecentres) and then, as they improved in capability, through mobile phones.

Infrastructure

Another techno driver of communications that's emphasised by Southwood is international infrastructure. Submarine cables were late in coming to the continent, and there were early battles over its deployment. State-owned enterprises often fought to keep control over what were gateways to communications, either independently or in alliance. Landlocked countries had to negotiate access with their neighbours, who might not be friendly or accommodating.

So it took time for much of the continent to become more, and more affordably, connected to what quickly became the most important aspect of communications, that is the internet. International connectivity and affordability remain weak in many countries now, but the burgeoning of connectivity in recent years, along with better mobile phones, has enabled internet to become mainstream for many in the way that early mobile phones became mainstream a decade or so earlier.

Behaviour

The last factor that I’d cite here is behaviour. Changes in governance, new technology and infrastructure provided platforms for the growth of mass market comms in Africa, but the demand side’s often overlooked in analyses of its development.

It was pent-up demand that drove early adoption of mobile phones in Africa. Users appropriated basic telephony to serve their unmet needs, and innovated to make use of mobiles in ways that operators had not intended nor anticipated. It was users sending mobile credit as a form of money transfer, for example, that intrigued the progenitors of mobile money platforms like M-Pesa.

Applications and services that enabled individuals to do their thing have usually proved more dynamic than those initiated by development agencies to serve specific purposes. That includes the use of social media to drive small businesses.

One important section in Southwood’s book considers African digital enterprise. Few African companies can compete with global giants, but African entrepreneurs have (unsurprisingly) been more successful at understanding the continent’s diverse markets and serving niches in those markets.

Transformation and its limitations

So the transformation of (tele)communications, within a generation, has been transformational in other ways. Access to communications was minimal in many countries in the 1990s; today it is much greater, and that has had great impacts.

But, as we know, it is constrained. Africa still has the lowest usage rates for internet of any continent. Connectivity is weak and for many unaffordable, especially in rural areas. Digital start-ups find it hard to raise sufficient capital. Some governments fear the impact of the internet on public protest as much as they would like to leverage its economic value, and shut it down from time to time as a result. Regulation is underdeveloped in key areas, including cybersecurity and electronic commerce.

Exogenous factors are critical too in determining what is and isn’t possible. Poverty’s the main constraint upon affordability. Conflicts undermine the prospects for investment (though mobile firms have proved quicker to invest in many places that emerge from conflict than other enterprises). Politics still plays a powerful part in determining the climate for investment and the quality of regulation.

And, while development agencies are now more conscious that African agency’s a better driver for development than agency-designed initiatives, the demand side is still often undervalued when designing services. There are examples still of development initiatives that are derived from donors’ aspirations rather than demand from populations on the continent.

Learning from the past?

These thoughts have been inspired by reflecting on the past quarter century of African communications, comparing different experiences within the continent and comparing them with those in other regions. Southwood’s book fleshes these experiences out through examples and interviews, and is a valuable reminder of how we got to where we are.

Has the past generation’s experience with communications been transformative? Unquestionably so, and possibly more in Africa than elsewhere because the starting point for telecoms back in the ’90s was so limited in scale. But it hasn’t diminished inequality as had been hoped and digital divides remain.

Has the ‘communications revolution’ resolved the problems of the continent, as some had hoped? Obviously not, but it has provided a platform for new approaches to be adopted by governments, new initiatives by businesses and appropriation by individuals that have strengthened social integration and economic opportunity.

Has its impact on other developmental factors been sufficiently explored and understood? I would say not. Too much analysis has focused on inputs rather than outcomes. The latter matters more for public policy and people's lives.

And what should we be learning from the past? Never an easy question, because things were done differently because the context then was different from that we know today.

One aspect that requires more thought, I’d say, is the impact that contextual differences have had on how things now stand. Many of the political and regulatory frameworks that govern communications in our current world are legacies from communications strategies and frameworks that were needed in the past. And many of the ways in which we think about communications markets derived from projecting back into the past rather than looking forward to the future.

We need to review the legacy of telecoms - the tale of how things were - to help us understand why we do things as we do today and what adjustments to the ways that we do things (which follow from that legacy) might help us do better in the future.

Image: Business on the high street of Paoua by DFID - UK Department for International Development via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)