As the Digital Society develops, more and more people worry that it won’t be the Utopia that internet pioneers once dreamed of; that it might even turn out to more like the dystopias that have featured in film and fiction over the years.

Rather than an era of empowerment, could the Digital Society be a surveillance society?

The most familiar dystopia

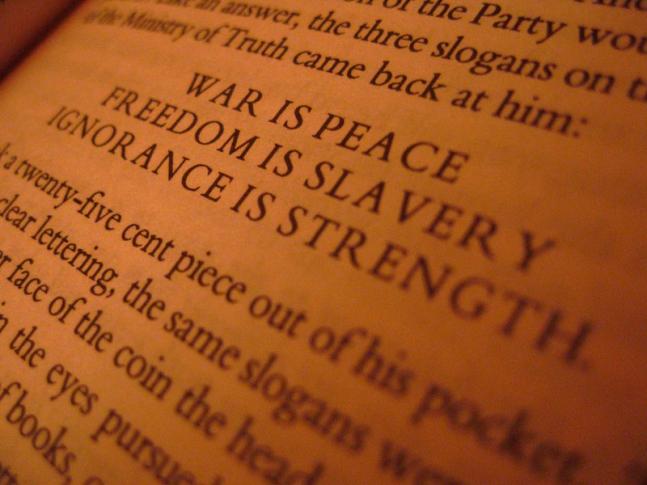

The best-known fictional dystopia is probably George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. That raised three prospects that are increasingly relevant today:

-

populist authoritarianism

-

pervasive surveillance;

-

and a loss of trust in the meaning of ‘truth’.

It’s worth re-reading (as I’ve just done). This blog asks if it has anything to say to us today?

The impact of Nineteen Eighty-Four

When I was young, Nineteen Eighty-Four was hugely influential. It’s not so widely read today but it’s the source of quite familiar phrases: ‘Big Brother’ as the name for a dictator, ‘Room 101’ for the worst thing you can imagine – both terms now used by TV entertainment shows; ‘doublethink’ and ‘thoughtcrime’, too.

It was written in 1948 by George Orwell, a British journalist and democratic socialist already noted for books on poverty and politics in Europe and for Animal Farm, a satire on the Soviet Union.

It was not intended as an entertainment, or as a prediction of the future, but as a warning about what could happen if democrats did not defend their liberties before it was too late. Here’s a summary for those who’re unfamiliar.

A summary

In Orwell’s imagined year of 1984, the world’s divided between three global superstates: dictatorships engaged in perpetual warfare. Oceania, where the novel's set, is governed by ‘the Party’, a perversion of socialism whose goal is to maintain power by suppressing individualism and perpetuating inequality.

People who live in Oceania – or at least those with non-manual jobs – are subject to continual propaganda and surveillance.

-

Individuality – ‘ownlife’ – is ruthlessly repressed.

-

‘Telescreens’ – always-on TV-like screens that double as surveillance cameras and audio recorders – are everywhere, in every room of every home, on every corner of every street.

-

The record of the past - newspapers, broadcasts, etc. - is altered constantly to ensure that whatever the Party says is ‘truth’.

-

Unorthodox belief – ‘thoughtcrime’, not just free expression but unspoken thought – is punished by death. Those purged are written out of history, as if they’d never been.

-

A new language – ‘newspeak’ - is under development, its aim to reduce to a minimum the number of available words, so that it becomes impossible to express unorthodox opinions.

I won’t go into the story itself – a clandestine romance between two subjects of this superstate (which is, by definition, also political rebellion) and the fate that then befalls them. No spoilers. This is, I’d say, a great novel and I’d recommend you read it – or, if you don’t have time, look for the fine and faithful film. But I will say something of four themes it raises, which are relevant to the Digital Society today – themes that are similar in some ways and different in others now from what Orwell imagined seventy years ago.

Political power and populist authoritarianism

Orwell wrote in the early days of the Cold War, when the antagonisms of the Second World War were being succeeded by new antagonisms between West and East (with the global South a battleground, metaphorical and subsequently sometimes more, between them). Populist authoritarian dictatorships – Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia – had led to war in the 1930s; the latter survived into the 1980s.

‘Primitive patriotism’ was crucial to what put those governments in power, and crucial to the Party’s rule in Orwell’s novel. Contrary to what we'd hoped, the internet age, so far, has seen resurgence in the kind of populist authoritarianism that relies on national, racial and religious identities to differentiate twixt us and them. This time it’s reinforced by digital discourse.

Civil and political rights

Orwell wrote in the year the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted. Those who govern his imagined future reject all rights - not just freedom of expression and association but freedom of thought itself. Nor do people have economic, social or cultural rights: on the contrary, they’re servants of economy, society and culture. The UDHR's increasingly challenged today as well, in principle and through new types of communication.

Truth, ‘fake news’ and propaganda

In Orwell’s world, the state controls all information and rewrites the past continuously to make it conform to what the Party wants today. ‘Truth’ is what the Party says it is. Orwell’s protagonist, Winston Smith, writes that ‘Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two makes four.’ The Party breaks him when it makes him believe that two and two make five.

Internet advocates have argued since the internet began that the it’s the most powerful tool for providing access to information that there’s ever been. This is true. But it’s also proved to be the most powerful tool for spreading misinformation and propaganda that there’s ever been as well.

Today too, many argue, we’re living in a ‘post-truth’ world, where the nature of what’s meant by truth is challenged. In some cases, that’s driven by state propaganda – one model of the future internet we fear. In others, it’s driven by individuals, by corporations, by political factions, by algorithms, by the collective actions of many uncoordinated voices. It’s hard to ‘speak truth to power’ when truth itself is questioned.

Pervasive surveillance

Here’s how the development of pervasive surveillance is anticipated in Orwell’s novel:

With the development of television, and the technical advance which made it possible to receive and transmit simultaneously on the same instrument, private life came to an end. Every citizen, or at least every citizen important enough to be worth watching, could be kept for twenty-four hours a day under the eyes of the police and in the sound of official propaganda, with all other channels of communication closed.

You could change that first sentence just a little to, say, With the development of internet and smart speakers … and - well, the point is obvious. The potential for pervasive surveillance has always been present in digitalisation. It’s more intense today than Orwell imagined for three reasons:

-

The data-gathering that underpins it isn’t just undertaken by governments but also, and more extensively, by corporations. (Orwell’s dystopia envisaged the replacement of capitalism; in this respect, at least, Aldous Huxley’s alternative dystopia, in Brave New World, feels closer to today.)

-

Data are now gathered and retained by default. This distinguishes the scope and scale of potential surveillance today from what happened in eastern Europe, say, before the fall of communism, and before today's technology, when enormous effort was required to gather far less data.

-

Data can now be analysed in extraordinary detail through AI – making pervasive surveillance much less labour-intensive, less costly and less evident to those surveilled, as well as more extensive in scope and scale.

So is Nineteen Eighty-Four relevant to us today?

As I said earlier, Nineteen Eighty-Four was written not as a prediction but as a warning against complacency in the defence of human rights and freedoms.

Let’s be clear: Orwell was no libertarian. Like me, he was a social democrat who believed in the power and necessity of government for public good – and in the need for people to work together to ensure that government delivers that. He’d have had no time for any 'declaration of the independence of cyberspace'.

Orwell (rightly, I think) foresaw that the impact of technology would tend to reinforce power structures rather than to undermine them, by enabling propaganda/disinformation and surveillance and potentially exacerbating inequality. He (rightly too, I think) foresaw the risks in undermining concepts of truth and falsehood.

Advocates of digitalisation have presumed – and still often presume – that benign outcomes for rights and democratic empowerment will follow from technology rather than analysing and preparing for potential outcomes, good, bad and neutral. Orwell suggests it would be wiser to anticipate malign outcomes and endeavour to prevent them.

Different contexts here are very different. Some governments today see digitalisation as fundamental to maintaining power. Others are committed to maintain and foster democracy and rights. Technologies are different too; while the power of corporations in this context is as important now as is the power of states. But the core message in Orwell’s warning – that democracy and rights depend on vigilance in their defence – surely remains a valid one.

Next week I’ll compare how the UN saw computers in development in the 1970s with the way it sees the digital society today.

Image: 1984, by Jason Ilagan, on Flickr Commons

David Souter writes a weekly column for APC, looking at different aspects of the information society, development and rights. David’s pieces take a fresh look at many of the issues that concern APC and its members, with the aim of provoking discussion and debate. Issues covered include internet governance and sustainable development, human rights and the environment, policy, practice and the use of ICTs by individuals and communities. More about David Souter.