This week’s post is the first of two on the digital economy.

UNCTAD – the UN Conference on Trade and Development – published its two-yearly Information Economy Report (IER) last week. It’s consistently one of the more interesting UN publications on the Information Society. Well worth a read.

This year’s is concerned with Digitalisation, Trade and Development and publication coincided with the first meeting of UNCTAD’s new Intergovernmental Group of Experts on E-Commerce and the Digital Economy. This post, longer than usual, summarises my contribution in the final session of that Group’s first meeting.

A growing part of economic life

E-commerce and the digital economy are increasingly important parts of the emerging Information Society, and of economic life. The IER notes that:

- The digital economy’s now worth some 6.5% of global GDP.

- Worldwide e-commerce sales reached $25.3 trillion in value in 2015.

- Exports of ICT services grew by 40 per cent between 2010 and 2015.

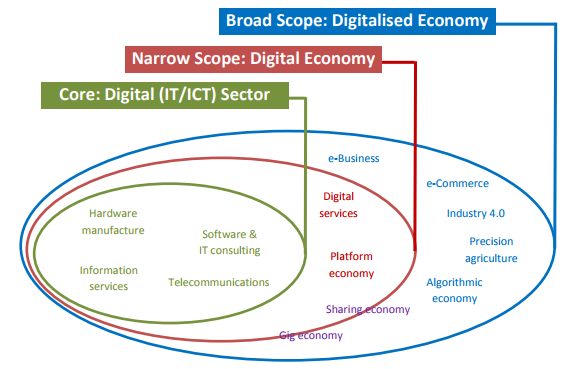

But what does that mean in practice? Building on work by Rumana Bukht and Richard Heeks, the IER distinguishes between three main areas of activity (see diagram):

- a core digital sector of ICT industries,

- the wider (but still narrow) digital economy of businesses that are fundamentally dependent upon ICTs, such as platform businesses,

- and the broad digitalised economy, those other areas of business which are increasingly affected by digital processes, systems and value chains.

Around these again lies a wider range of economic activity which is little digitised.

Source: Bukht & Heeks, Defining, Conceptualising and Measuring the Digital Economy, Manchester University, 2017.

You can see this pattern emerging everywhere, but with big variations among and between developed and developing countries.

These were the five reflections I think emerged from discussions at the UNCTAD Group.

Not everything is going to go digital

First, we should not think of the digital economy in isolation from the rest of economic activity around it, or see it as a substitute for every older way of doing business. Some economic sectors will be quick to change, but others slow. In many cases e-commerce will complement what’s gone before, rather than replacing it.

And that’s as it should be. The destruction of traditional business models is not something we should think of as a virtue. The livelihoods of many people, particularly the most vulnerable, depend on them and will continue to do so. Making sure that no-one’s left behind – the core target of the UN’s Sustainable Development Agenda – includes ensuring that digitalisation’s not responsible for leaving them behind.

So the digital economy should build on, adapt and enhance economic activity. It should seek to integrate the old and new.

It has domestic and international contexts

Second, e-commerce and the digital economy matter in both domestic and international contexts. We need to pay attention to what’s happening in both. And we should be concerned above all with their impact.

We should not focus on growing the volume of e-commerce for its own sake, but on the contribution that this makes to commerce as a whole and – more important still – to trade’s capacity to generate greater economic value (and, through that, greater social welfare) for developing countries, their businesses and citizens. This should be a developmental project, not one of trade statistics.

In domestic markets, that means that we should want to see more than growth in the volume of e-commerce; we should want to see that growth boosting local economies. And as this is a developmental project, we should want to see domestic growth becoming more inclusive, enabling SMEs, women entrepreneurs and rural businesses, for example, to benefit more than they do from current business environments.

In export markets, we should want to see a growth in cross-border trade, not just between North and South but amongst developing countries themselves. Cross-border trade is particularly weak in Africa, but it’s a crucial engine of economic development. A key question for us should be how to capture that for local enterprise.

The digital economy is not a panacea

Third, the digital economy is not a panacea. It offers opportunities, but also poses threats. These differ between countries and they’re related to existing digital and development divides.

The capacity of different countries and communities to take advantage of e-commerce varies widely. Some countries, sectors, individuals are far better placed to benefit from them than others.

In domestic markets, the biggest constraints on participation in the digital economy are poverty and skills. The poor lack the resources to buy the goods and services that will generate value for local businesses (digital or non-digital), and lack access to the capital they need to improve their economic potential.

These digital and development divides are hard to bridge. They follow on from one generation of technology to another. Those with more money, more education and more skills are better placed to take advantage of e-commerce than those with fewer of these assets. We can’t overcome them without addressing underlying structural inequalities in income and capabilities.

That’s true of countries as well as individuals. In export markets, the challenge is especially acute for least developed countries (LDCs). Most LDCs primarily export commodities, which are less susceptible to value-enhancement through e-commerce than the manufactured goods or services which form a larger part of wealthier countries’ trade portfolios.

There is a risk that LDCs will fall further behind, therefore, as markets digify. But that doesn’t mean that LDCs can ignore the digital economy; in fact, the opposite. The bigger risk's that they will fall further behind if they don’t seek to match competing countries by engaging with the digital economy. Global buyers will prefer trading partners that are capable of doing business digitally over those that aren’t.

Policy intervention in ICTs, trade and skills

Fourth, three kinds of policy intervention are needed in order to address the opportunities and risks the digital economy throws up. These are concerned with ICTs, with trade, and skills development.

There’s a lot of discussion in UN fora about the digital divide and connectivity. But digital divides are not just matters of connectivity or affordability. They are matters, too, of content, capabilities and education. And, as I mentioned earlier, they’re underpinned by problems of structural inequality within society. We won’t overcome digital divides, or the limits to peoples’ economic opportunities, unless policies for development also address those structural inequalities. (This is also true where the gender digital divide’s concerned.)

There’s a lot of discussion, too, about legal and regulatory frameworks. This must concern more than regulatory frameworks for networks and services, which facilitate competition and investment. Most obviously, It should include frameworks for enabling e-commerce through data protection, digital signatures, and cybersecurity.

But, just as important as these ICT frameworks are the non-ICT frameworks that govern how easy (or how hard) it is to set up or run a business. And, in international trade, the frameworks exporting goods and services across international borders, frameworks which can themselves be facilitated by new technology (though not as easily as some believe).

There’s discussion, finally, of skills development. Businesses and consumers that are digitally literate are much better equipped to take advantage of the online world in general and e-commerce in particular than those that aren’t. Skill shortages are already problematic in many cases. Addressing them takes time, as skills need to be entrenched in education and employment. Skills development should nonetheless be a priority, for consumers, for businesses and for those concerned with export promotion and trade facilitation.

All of these frameworks need to be addressed together, within a consistent overarching policy. This will require dialogue between and action from many different stakeholders, including national governments (and different ministries within them), global and local businesses, donors and development agencies.

Don’t underestimate the pace of change

Lastly, the digital economy is changing fast. I’ve written in earlier posts about the speed with which new ICTs are becoming prevalent in developed countries – cloud computing and big data, 3D printing, artificial intelligence, machine learning, algorithmic decision-making. These are already having major impacts on developed country business markets.

Can developing countries exploit these new technologies as well, in order to keep up with global market changes? If so, how? What policy frameworks do they need in order to engage effectively with them? And if some can’t exploit them effectively as yet, what policy frameworks are needed to ensure they – and their people – don’t lose out?

Looking forward: four suggestions

There was excitement at UNCTAD’s Expert Group about the opportunities for developing countries, but also concern about the barriers to change and risks involved. How should they take things forward? I made four suggestions.

Consider both positives and negatives

First, policy approaches should not focus just on positives. We need to maximise the opportunities of e-commerce, but we also need to address the barriers and mitigate the risks. That includes ensuring that we actively seek to meet the needs of those who could be left behind by the digital economy because they can’t participate effectively. Policy approaches that seek both to maximise opportunities and mitigate risks are much more likely to reap benefits for society as a whole than those that focus just on opportunities.

Deal with data deficiency

Second, we have a real deficiency of data. We don’t know enough about what is currently happening, and we don’t have mechanisms in place to monitor developments. More accurate, reliable and timely data are essential for policy development. Governments, businesses and agencies like UNCTAD need to work together to build that data base and monitor developments.

Understand what’s happening

Third, we need a clearer view of what’s already happening today. With funding from its donors. UNCTAD’s begun publishing rapid e-commerce readiness assessments of LDCs. These are valuable. But we could also do with rapid assessments of experience of the impact of e-commerce in individual sectors and individual countries. The textile industry in Bangladesh might be a case in point.

Unpack the detail

Fourth, there’s a need to look in greater detail at particular aspects of the digital economy in developing countries – to look for standards, norms and practices that might have wider resonance. Several candidates for study emerged in the Expert Group’s discussions. The special needs of LDCs or small island states, for example. Enabling SMEs (small and medium enterprises) to benefit from e-commerce opportunities. Supporting women’s enterprise. Building digital literacy among businesses and their consumers. Payment and delivery mechanisms. Establishing local platforms for e-commerce that can compete with global corporations. Improving access to global platforms for developing country firms.

To summarise

E-commerce and the digital economy are coming to developing countries, and they bring with them opportunities and threats. Opting out is not an option: global markets will be digitised, and every country needs to participate in digitised markets if it is to retain its place in the global economy.

This won’t be easy for many developing countries, especially LDCs, but it’s in the interest of the whole global economy, not just those countries, that they don’t get left behind.