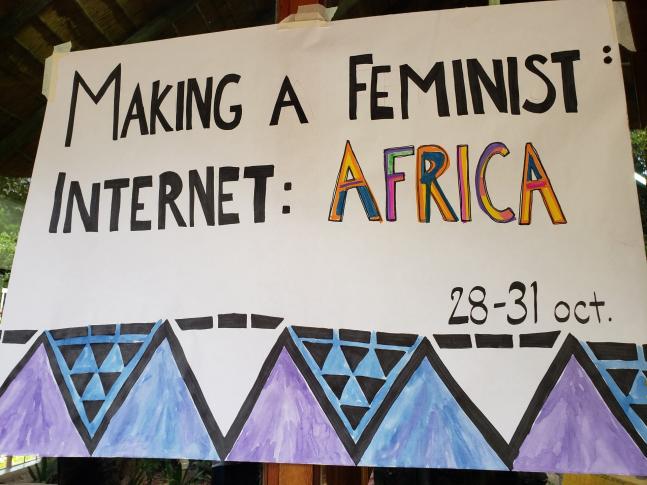

What makes the internet so exciting? How can we make the internet more accessible and safe for African women? How can we ensure that when we discuss issues of access, we are not excluding those most marginalised among us, such as refugees and women living in disconnected rural areas? How do we build solidarity among African feminists both online and offline? How do we take movements that start online and transform them into tangible effective movements offline? And last but not least, how do we go about creating brave but also safe digital spaces? These were some of the questions that came up during the very first "Making a Feminist Internet: Movement building in a digital age in Africa" convening, held in Johannesburg from 28 to 31 October.

Organised by the APC Women’s Rights Programme, the four-day Making a Feminist Internet (MFI) event brought together feminists from 18 African countries, and started with the discussion of what excites us about the internet. It was really enriching to learn different roles that the internet plays in people’s lives. Some of the attendees stated that the internet has given them power to mobilise and take action as well as the ability to be brave. For others, the internet has provided them with a community in places where they thought they were the only ones with intersecting identities, an example being the Zimbabwean Black queer community.

One of the most important takeaways for me was the discussion around access, which is the first principle of a feminist internet. Though it is a topic that many of us might think we understand, there are so many nuances around the topic that oftentimes, even when we think we are being inclusive in our fight towards creating a world where everyone has easy and affordable access to the internet, there are people we are still leaving behind. An example of this is women living in conflict zones who are barely if ever brought up in dialogues around this topic. As stated by one of the attendees, this is worrisome as women and children in international and internally displaced persons (IDP) refugee camps are some of the most vulnerable women in the world. Not only are they constantly under the threat of physical and sexual violence, but their lack of access to the internet also means they cannot share their own stories and realities. Their stories are instead told by journalists, bloggers and other well-meaning Westerners in very narrow and harmful ways. Moreover, not only is their consent never obtained, but they also lose agency when images of their bodies and those of their children are shared on social media accounts by influencers with millions of followers.

The conversation on access also brought up the fact that the language that activists and techies often use when writing on issues around internet rights and internet access is English. Unfortunately, what this means is that activists living in non-English-speaking countries sometimes get left behind. In an effort to address this issue, a side meeting was organised at the MFI convening with attendees from French-speaking African countries, in order to find ways to be more inclusive. This was extremely important, because for many activists in these countries, not only do they have to deal with repression from their own governments, but also language barriers that make it almost impossible for them to join in solidarity with other activists around the continent and the globe. Furthermore, the language used in ICT circles and around internet governance policies is complicated and difficult to understand, even for native English speakers.

Another interesting conversation I had in one of my small groups was around what feminism means for the everyday African woman, especially when you consider the fact that a lot of African women who identify themselves as feminists come from privileged backgrounds and have access to the internet and African and Black feminist theories. What then happens to the women in rural areas who are doing what would be considered feminist work but don’t necessarily identify themselves as feminists, due to both lack of access and understanding of what feminism is? To ensure that diverse voices are heard, my group decided that it is extremely important to ensure we do not isolate these women, whom our work is supposed to be representing. It is important that we stand in solidarity with them by combining our online work with the work a lot of African women are already doing on the continent, even if they do not necessarily identify as feminists, for effective solutions to end gender-based violence, LGBTIQ violence and lack of access.