The use of digital devices such as mobile phones and laptops has become a day-to-day necessity across the majority of global communities, although these needs are often reshaped into wants by pervasive corporate marketing encouraging people to buy more, newer, supposedly more prestigious devices. This kind of unchecked accumulation is both unequal and unsustainable. “We need to redirect global society to a more sustainable future with equity and environmental sustainability as a priority,” advises APC’s Guide to the circular economy of digital devices.

In the fifth part of Our Circular Future series, we spoke with Leandro Navarro from Barcelona-based APC member Pangea, who explored case studies in Spain and the Netherlands looking at ways to build mobile phones that are socially and environmentally responsible as well as how principles of reuse are essential for social inclusion.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You contributed to two case studies in the Guide to the circular economy – one looks at the Fairphone model of producing mobile phones with minimal environmental impact, and the other is on the eReuse project that refurbishes devices like mobile phones and laptops. Since the guide was published have conditions improved or worsened?

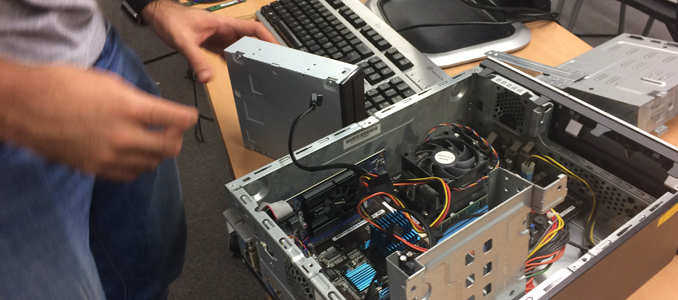

Nothing major has changed but at the same time things have evolved. People have learned from experience by making mistakes and improving. Donors [of secondhand devices] are more aware that when they are donating equipment, they are not always giving something useful, and refurbishers are also getting more pragmatic. Not everything that works is usable and they are learning to decide whether to accept a donation or whether to recycle something if there is no demand for it. And if there is demand, what amount of effort, parts and time do they want to spend on devices so that they can be cost effective? They are more aware of the market and they’re optimising better so it's less idealistic and more pragmatic.

Recipients are also learning that we cannot provide them with their “ideal” computers but rather whichever ones we receive, though these are better nowadays than a few years ago for usability. We also found people that get secondhand devices not only because they cannot afford new ones, but because they are concerned with the environmental impact. Still, there is this feeling when you prepare computers for secondhand use that in one way it helps but in another it repeats the divide between those who can afford a new device and those who have to accept a secondhand one.

Video: Exploring the transition to a collaborative and circular consumption of electronics. Video courtesy of eReuse.

When the recipients are not individuals but organisations, for instance schools, we’ve been experimenting more with the idea that instead of buying a device, you buy the right to use it. You agree on a fair maintenance fee so someone is keeping the devices you need in good shape. Then if one fails, it is replaced by another one because you are paying for the service and not ownership.

Ownership is a human habit of keeping something only for yourself, but we have devices because we want to use them and it's also a way to showcase our status. There are some people who are proud of the devices they have, but that’s something that is changing because we are realising the risks and dangers of e-waste. Therefore you cannot be purely proud of your devices, because then you become more part of the environmental problem. If you're reading this, you’re part of the environmental problem.

I think in that sense organisations and individuals are getting more realistic about the pollutants and the environmental impact of the devices they accumulate. We also realised when talking to public administration that decisions are made during procurement, without understanding fully that when you buy devices, you buy them for a certain period and they can have a second life. This means that when you procure devices, you have to care about where they come from. You are becoming part of the manufacturing process choices in a way.

In the case of Fairphone, if you buy a device that is not designed to be durable and the manufacturer doesn't commit to maintain the firmware and operating system or you cannot change the components, you made a mistake already when you procured it and it cannot be amended. With some donations we have to tell people, “Look, this device is proprietary, it has a lot of hidden costs. No one will really be able to use it. You need to recycle it even though it could work, but it was designed for a single use.”

Are you seeing any encouraging practices or other local cases of people connecting with circular technology?

At the Technical University of Catalonia in Barcelona (and with the participation of Pangea), we have cooperated on development projects where students and staff bring knowledge and devices to remote areas, in our country and beyond. Not only do they give useful, pretested devices, but increasingly they also bring back the waste that came out of old devices.

Another example is initiatives in Europe around the Green Claims Directive, or the sustainable product initiative, which is about requiring products entering Europe to comply with certain sustainability standards. This is encouraging because it means access to information, requiring manufacturers to declare and comply with environmental and labour right regulations. Also, by digitalising this information and providing it free, prospective buyers can choose more carefully.

Directives that forbid false or unsupported green claims, or “greenwashing”, are also useful. Even the word “green” is greenwashing. You have to talk about a specific quality, you cannot just call something “green”. You can say “durable”, and durable up to what lifetime and how this lifetime is measured. That is more credible. The requirement that you support claims with verifiable proof can help in avoiding non-sustainable products.

Of course it introduces bureaucracy, as always, but nowadays especially in developed countries, a product in the formal economy always comes with maintenance instructions, and everything has to be declared. One challenge is how to integrate the informal economy into these kinds of requirements so that we do not create another barrier of entry. We need to be careful to avoid isolating or making a divide between those who can comply with formal regulations and those who can't.

When we look at the future of circular economies, how do you see it evolving or how would you like to see it evolve?

It’s nice that you say, “How do you want it to be?” because it’s different from what I fear it will be.

In terms of hope, when you look at items in homes like glasses, cutlery or plates, you reuse them as much as you can, and they last a long time. So that’s the idea – that we do not throw single-use products in the waste expecting that recycling will remove it from our eyes and drop it somewhere else. I think the idea is to go to a mostly circular economy with exceptions – instead of an exception with some circularity, which is what we have now.

I tend to always reference the Global E-waste Monitor that says about 7% of e-waste becomes secondary raw materials and the rest is a problem. We don't even know what happens to 83% of it. As usual there is a lot of inequality in transboundary movement of e-waste. Typically useful things go to richer communities, so inequality produces inequality.

Do you see any ways to work around this to move in a better direction?

We can compare cars with mobile phones. It would be nice in the future if cars remain something that people often tend to buy in the secondhand market and don’t become like phones, while phones become like cars and last many years. Then you can be proud of your vintage phone that has better materials or is more beautiful than modern ones. That is happening with computers, but phones are still so short-lived.

What would you like to see in another guide to the circular economy?

One is more use cases, because the reality is not the abstractions we made to explain things, but particular cases to show interesting tricks and methods to do things in different communities. How can we create a future where communities – not the planet, not the region – but any community can self-determine its choices and be more autonomous in implementing them? It's much easier to come up with a viable model if you realise what another community similar to yours is doing, rather than bridging the gap from one model that works in a very different place from yours. When we have more cases we can compare, discuss, argue and build our own lessons by looking at alternatives. It’s not enough to understand; we need to be able to transform that into local action.

I think one useful aspect of the current guide is it provides a starting point, but I would dream about providing some more actionable templates so that communities can adopt them and implement them locally to enable action.

What advice would you give to an organisation looking to engage in technology and the circular economy?

The most clear advice I would give is, don’t do it alone. Look around and you will find a lot of initiatives, people and organisations sensitised to this work with experience in different aspects. More than thinking, “What can I do?”, try to see how you can complement other organisations and do something better informed and bigger that could have a significant impact on your community. Many companies and public organisations are legitimately interested in including the social and environmental footprint. That requires a process of discovering and interacting with partners in your community and building such partnerships. Once you have a partnership you can think about doing advocacy with the power of the community. The worst thing is when you try on your own to repeat mistakes that someone made before you, but you just didn't know.

There must be a combination of hope and action. I always think of a sentence from a visionary in my region who used to say that poverty is not there to be understood, but to be eradicated. You need to understand first, in order to avoid mistakes, but you shouldn’t forget that we are fighting a struggle in our society and we need to live within limits. That’s a change we have to implement, otherwise we will understand and burn at the same time.

Our Circular Future series

- In this new series, we reconnect with members who contributed to our guide on the circular economy of digital devices, this time about their vision for the future of these economies. In part one, we speak with CITAD about what is needed in the right to repair movement, emerging trends and lessons learned and missed. Read: “The bottom line is to understand that linearity and growth will not go together”: Introducing Our Circular Future, a series on the future of circular economies

- In part two of this special series, we spoke with Florencia Roveri at our Argentina-based member Nodo TAU. From supporting youth with future e-waste projects to exploring the challenges to electronic waste treatment, Nodo TAU has been advocating for better ICT recycling practices in the community. Read: Our Circular Future: “Our strength comes from addressing multiple needs like the environment, youth employment and using technology for social use”

- In this third part of our special series on Our Circular Future, Syed Kazi of Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF) in India talks to us about how one of the highest-consuming regions of the world needs to urgently adopt circular economy approaches across all sectors. Read: Our Circular Future: "We must adopt the circular economy without waiting for the government to say, ‘Hey, this is a time bomb now'"

- In this fourth part of the series on Our Circular Future, Colnodo’s Plácido Silva tells us about good and bad electronic waste management practices in Colombia and their impact on education. Read: Our Circular Future: "We don’t want to see the circular economy become a new marketing campaign"

- In the fifth part of Our Circular Future series, Leandro Navarro from Barcelona-based APC member Pangea explores ways to build mobile phones that are socially and environmentally responsible as well as how principles of reuse are essential for social inclusion. Read: Our Circular Future: "If you're reading this, you’re part of the environmental problem"

Further reading: APC's Guide to the circular economy of digital devices describes the concepts and processes of circularity and summarises the key challenges and opportunities, including for policy advocacy.