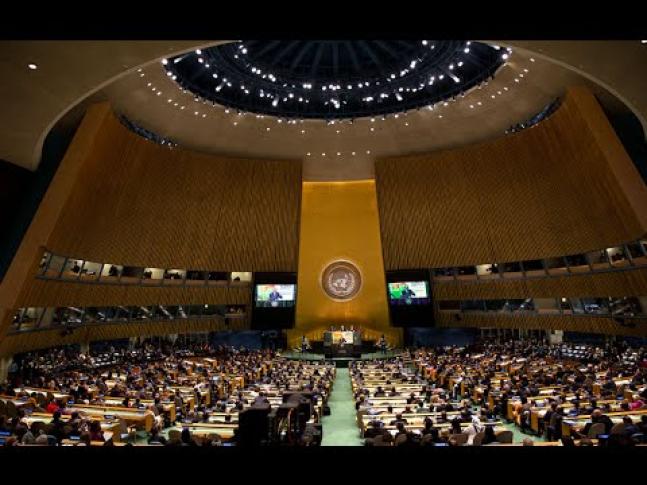

As the UN General Assembly’s Third Committee wraps up its work this this week, it has adopted two resolutions reinforcing the responsibility of states to protect human rights online, specifically for journalists and human rights defenders.

1. Safety of journalists and the issue of impunity

Adopted by consensus, the resolution on the safety of journalists and the issue of impunity (A/C.3/72/L.35/Rev.1) advances three critical issues with respect to human rights online: gender-based violence and harassment of women journalists online; the intentional disruption of communication networks; and the importance of encryption and anonymity tools for the work of journalists.

Addressing threats against women journalists, online and offline

Building on previous UNGA and Human Rights Council (HRC) resolutions on the safety of journalists, the resolution acknowledges “the specific risks faced by women journalists in the exercise of their work” and underlines “the importance of taking a gender-sensitive approach when considering measures to address the safety of journalists, including in the online sphere, in particular to effectively tackle gender-based discrimination, including violence, inequality and gender-based stereotypes, and to enable women to enter and remain in journalism on equal terms with men while ensuring their greatest possible safety, to ensure that the experiences and concerns of women journalists are effectively addressed and gender stereotypes in the media are adequately tackled.”

Gender-based attacks on women journalists online are increasingly being recognised as a violation of international human rights law, both because they are an assault on women’s human rights to freedom from violence and freedom of expression, and because they interfere with the public’s right to access to information and a free press, fundamental tenets of a democratic society. The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) recently released an updated General Recommendation on violence against women in which it characterised gender-based violence against women as manifesting “in a continuum of multiple, interrelated and recurring forms, in a range of settings, from private to public, including technology-mediated settings.” Cyberstalking, harassment, misogynist speech, threat of blackmail, non-consensual sharing of intimate content, viral "rape videos", and doxxing, are examples of acts of gender-based discrimination and violence that are committed, abetted or aggravated, in part or fully, by the use of information and communications technologies (ICTs). Such tactics are used to discredit, intimidate, and silence women journalists. Often the response to online gender-based attacks is to tell women journalists to not use social media and to minimise their online presence. But not using social media can be crippling for journalists who may rely on such platforms to carry out their work, in particular for communicating with sources and their readership. The resolution correctly identifies online attacks as a barrier to women entering and remaining in journalism on equal terms with men.

The resolution echoes the 2016 HRC resolution on the safety of journalists by unequivocally condemning “the specific attacks on women journalists in the exercise of their work, including sexual and gender-based discrimination and violence, intimidation and harassment, online and offline.” However, this resolution goes further in calling on states to “tackle sexual and gender-based discrimination, including violence and incitement to hatred, against women journalists, online and offline, as part of broader efforts to promote and protect the human rights of women, eliminate gender inequality and tackle gender-based stereotypes in society.” Among measures recommended in the resolution are supporting the judiciary, law enforcement and other relevant actors in considering training and awareness raising related to the safety of journalists, including specifically sexual and gender-based discrimination and violence against women journalists, as well as the particularities of online threats and harassment of women journalists.

Network shutdowns as undermining the work of journalists

Intentional disruptions of access to information online, including by making the internet inaccessible or effectively unusable for a specific population or within a location, represent a violation of international human rights law. The HRC recognised this with its 2016 resolution on the promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights and the internet, and called on all states to refrain from and cease such measures. Since the adoption of the HRC resolution over a year ago, network shutdowns continue to take place in different regions around the world. At least 61 shutdowns have been imposed so far in 2017 alone.

While network shutdowns impact a broad range of rights of the people whose communications have been cut off, as well as those trying to communicate with them, they have a specific impact on journalists, who rely on communication networks to carry out their work. With this resolution, the UNGA recognised network shutdowns as aiming to undermine the work of journalists in informing the public, and called upon all states to cease and refrain from these measures, which it characterised as causing “irreparable harm to efforts at building inclusive and peaceful knowledge societies and democracies.”

Encryption and anonymity of sources must be protected

While not a new element, the resolution reinforces that in the digital age, encryption and anonymity tools have become vital for many journalists to freely carry out their work, including to secure their communications and to protect the confidentiality of their sources. This comes at a critical time, when governments around the world are considering measures that would limit access to and use of encryption and anonymity tools in the name of national security and public safety, a move that would have a devastating impact on the free press. In its recently released Freedom on the Net report, Freedom House observes that restrictions on encryption have continued to expand, as "at least six countries – China, Hungary, Russia, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam – recently passed or implemented laws that may require companies or individuals to break encryption, offering officials so-called backdoor access to confidential communications." The resolution acknowledges that journalists are particularly vulnerable to becoming targets of unlawful or arbitrary surveillance or interception of communications, and calls upon states not to interfere with the use of encryption and anonymity tools, and ensure that any restrictions thereon comply with states’ obligations under international human rights law.

Looking forward

The resolution, which was led by a core group of states, consisting of Greece with Argentina, Austria, Costa Rica, France and Tunisia, was adopted with co-sponsorship from a broad range of other states. Nonetheless, resolutions of the Third Committee are non-binding, making follow-up on implementation key for holding states accountable. In this regard, the resolution requests the Secretary-General to further assist in the implementation of the resolution and to report to the UNGA’s 74th session (two years from now) and to the Human Rights Council at its 43rd session (in February/March 2020), with a special focus on the activities of the network of focal points in addressing the issues of safety of journalists and impunity and taking into account the United Nations Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity and its follow-up.

2. Human rights defenders

The Third Committee also adopted by consensus a resolution on the “Twentieth anniversary and promotion of the Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms”. While this resolution, which was led by Norway, does not have a specific focus on human rights in the online context, it does express grave concern about the considerable and increasing number of threats, risks and dangers faced by human rights defenders (HRDs) online as well as offline, consistent with text in previous resolutions on human rights defenders.

The resolution comes at a time when we are seeing increasing and sophisticated attacks on HRDs through their digital communications by both by state and non-state actors. Methods include communications surveillance, malicious hacking (through malware and ransomware), and restrictions on use of encryption and anonymity tools. HRDs rely on digital communications, and in all regions of the world, these critical tools are being turned against them, jeopardising their work, and used to harass, discredit, intimidate and attack them.

The draft resolution contains important commitments from the international community to do more to promote and implement the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders. Importantly, it condemns all acts of intimidation and reprisal by state and non-state actors against human rights defenders who seek to cooperate, are cooperating or have cooperated with subregional, regional and international bodies, including the UN, and strongly calls upon all states to give effect to the right of everyone to unhindered access to and communication with international bodies, including the UN and its different human rights mechanisms, as well as regional human rights mechanisms. Critical to this is the UN itself adopting more secure communication practices, especially with human rights defenders, civil society and victims of human rights violations who may be under surveillance and face reprisals as a result of communicating with the UN. The Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, David Kaye, has recommended that UN entities "revise their communication practices and tools and invest resources in enhancing security and confidentiality for the multiple stakeholders interacting with the Organization through digital communications." Kaye adds: "Particular attention must be paid by human rights protection mechanisms when requesting and managing information received from civil society and witnesses and victims of human rights violations." In implementing this resolution, states should invest resources in and put pressure on the UN to address Kaye's recommendation.

With the resolution, the UNGA decided to devote a high-level plenary meeting of the General Assembly at its 73rd session (in 2018) to mark the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration. The modalities for that event have not yet been established. The resolution calls on the Secretary-General to undertake a comprehensive assessment and analysis of progress, achievements and challenges related to the ways in which the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, as well as other relevant UN actors, have given consideration to the Declaration in their work, and assist states in strengthening the role and security of human rights defenders. The Secretary-General is instructed to prepare this report in cooperation with the Special Rapporteur on HRDs and in consultation with states and a range of other relevant stakeholders, including national human rights institutions and civil society. This means that civil society will have the opportunity to inform the conclusions and recommendations in the report, which should concern effective technical assistance and capacity building, as well as good practices.

Finally, this year's HRD resolution marks a return to consensus after the 2015 and 2016 resolutions at the UNGA and the HRC, respectively, were voted on. Though some compromises were made to reach consensus, the fact that the General Assembly spoke with one voice in "underscoring the positive, important and legitimate role of human rights defenders in promoting and advocating the realization of all human rights" is significant. Following the adoption of the text, a number of states reflected on areas of the text that did not fully reflect their views despite joining consensus. Of particular note were interventions from China, which disagreed with "preconceived notions that the role and activities of HRDs are legitimate" and emphasised that HRDs must carry out their activities in a peaceful and lawful way, or face sanction by the law; and from Azerbaijan and Turkey, which objected to positive references to the Special Rapporteur on HRDs, who they characterised as not conforming with the code of conduct for Special Procedures mandate holders, ostensibly based on his criticism of the treatment of HRDs in their respective countries.

As with all UN resolutions, continuous monitoring and pressure are needed to ensure that states implement their obligations. The Secretary-General report and high-level plenary meeting are excellent opportunities for stocktaking and dialogue on effective measures to protect the work of HRDs. States should use these opportunities to reflect inward on their own practices and how to better promote and protect the work of HRDs nationally.

Resolutions adopted by the Third Committee are formally adopted by the UNGA plenary some time in December.