BACKGROUND

Mike Jensen, Association for Progressive Communications (APC)

The issue of climate change adaptation and mitigation is rising ever higher on humanity’s sustainability agenda. The promise of the digital revolution has come at a huge cost, including the massive environmental impact of the exploding number of digital devices that are produced and disposed of within a few years. Globally, there are estimates that 27 billion networked devices will be sold in 2021, up from 17 billion in 2016. Most devices last less than five years.

Digital technologies can help us fight climate change, environmental degradation and pollution, but we must significantly reduce their impact on the planet. The negative effects of digital technologies are diverse, from the pollution and health impacts of the extraction of minerals for digital devices, to the energy used in their manufacture, and the poisons released in aquifers resulting from improper disposal.

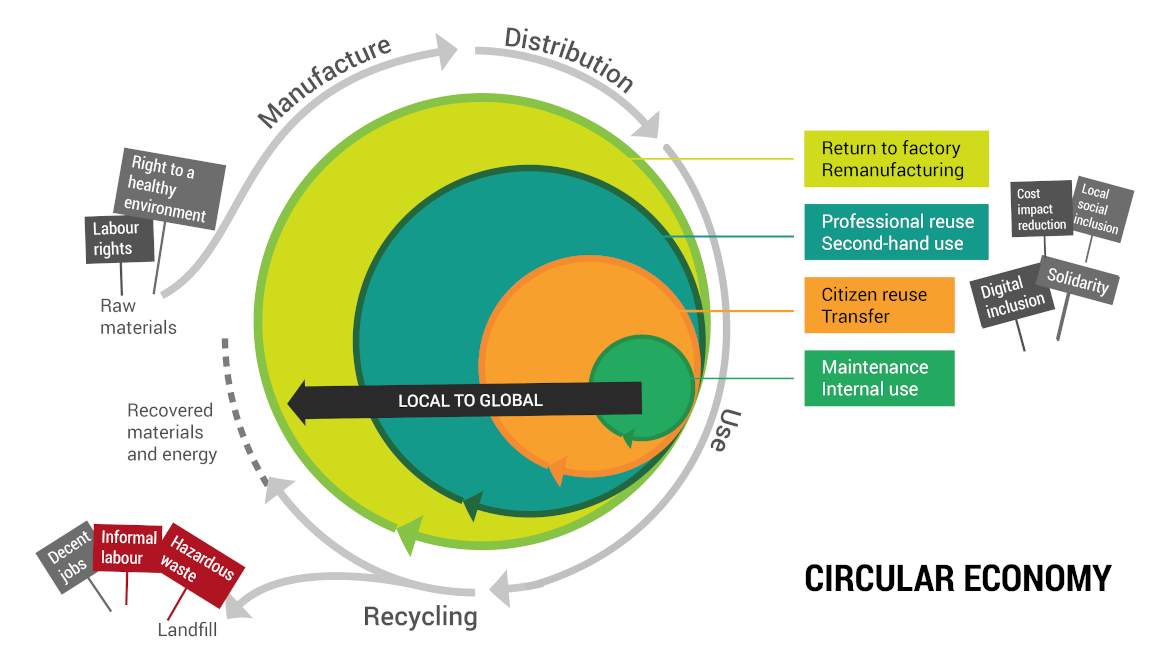

One of the key strategies in mitigating the environmental impact of digital devices is to treat the devices as part of circular economies. These strategies are not unique to the digital realm, and can be used in all aspects of the economy to reduce the use of polluting or exploitative inputs, minimise energy consumption in manufacture and operations, expand the lifespan of devices through repair and reuse, and improve effectiveness of recycling.

The guide is being released following the publication of the Global Information Society Watch (GISWatch) 2020 report, which was launched earlier in 2021 and explores many of the same topics on environmental sustainability, digital rights and circularity. GISWatch’s country, regional and thematic reports offer a critical lens on digital economies and how they relate to the goals of sustainable development, with case studies from countries across the global South. Both the guide and GISWatch 2020 aim to contribute to the goal of mobilising collective action for environmental justice and sustainability that APC and its partners promote.

The full edition of the Guide to Circular Economies of Digital Devices is available here.

The Association for Progressive Communications (APC) is currently working to promote, develop and adopt practices, models and systems that are environmentally and socially sustainable among our network. To raise awareness of the potential value of the circular economy model for digital devices, and to describe methods of implementing them, APC commissioned the development of this guide by Leandro Navarro (UPC and Pangea) and Syed Kazi (Digital Empowerment Foundation).

This preview was developed with contributions from Jes Ciacci (Sursiendo), Florencia Roveri (Nodo TAU), Peter Pawlicki (Electronics Watch), Alejandro Espinosa (Computer Aid), Patience Luyeye, Rozi Bakó (Strawberrynet), Julián Casasbuenas and Plácido Silva (Colnodo), and Shawna Finnegan (APC).

This edition of the guide is a preview, to solicit feedback and suggestions prior to the publication of the full document. It comprises an introductory chapter which outlines the need for circular economies of digital devices and describes the scope of potential interventions and issues that are raised. Chapter 2 consists of a series of case studies of projects which implement elements of the circular economy for digital devices. Future chapters will reflect on lessons and best practices from case studies, and will include recommendations for local and collective action.

WHY DO WE NEED CIRCULAR ECONOMIES OF DIGITAL DEVICES?

Written by Leandro Navarro (UPC and Pangea) and Jes Ciacci (Sursiendo)

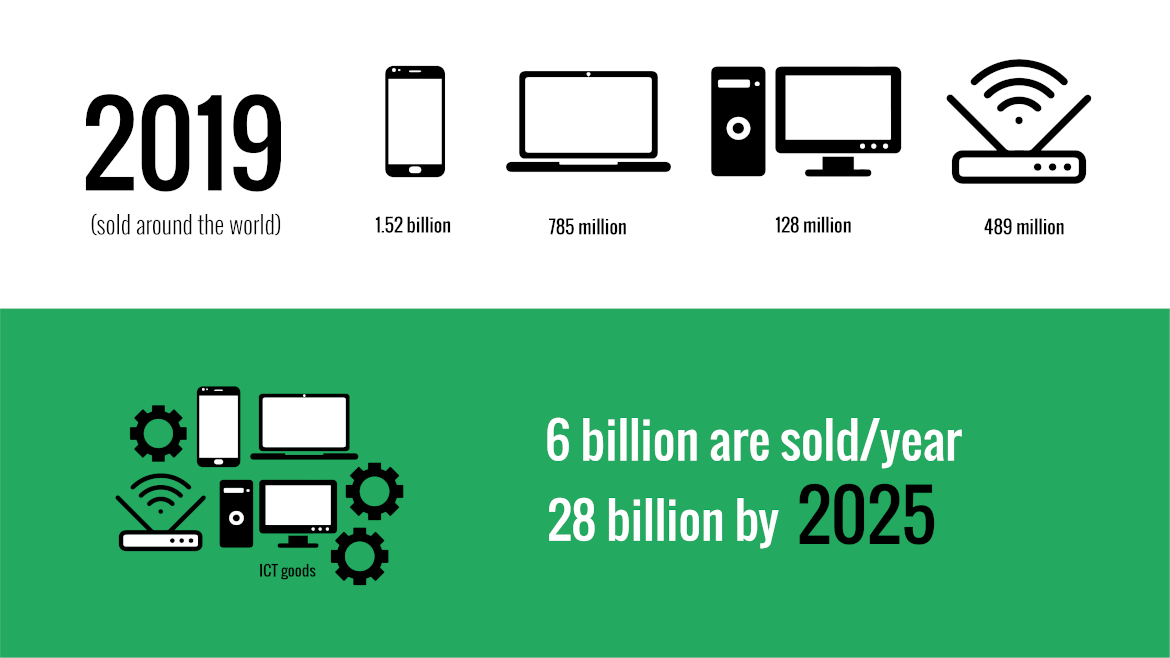

Imagine the evolution of our digitally connected world. There are now more digital devices in the world than people. In 2019, humans around the world purchased approximately 1.52 billion smartphones, 785 million laptops, 128 million desktop computers, and 489 million Wi-Fi routers, figures that are expected to grow exponentially over the next five to ten years with new “smart” technologies.

We live on a planet that follows natural cycles and boundaries. Climate change, biodiversity loss, land erosion, pollution, and resource depletion are the direct result of human impacts on the planet. The digital device on which you are reading this guide impacts our planet at each process in its life cycle.

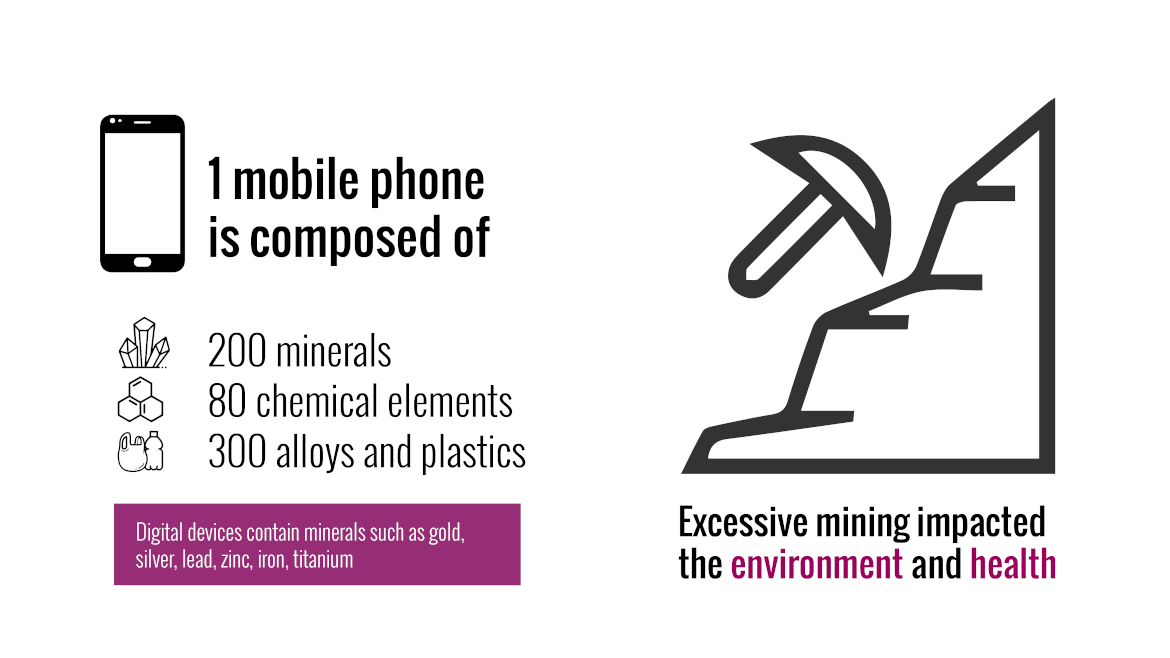

Do you know how your digital device was created? A mobile phone is composed of over 200 minerals, 80 chemical elements, and 300 alloys and plastics. Minerals are part of our daily lives, but we know very little about their impact on our planet.

More than 230 civil society organisations from around the world published a statement in September 2020 that called on the European Commission (EC) to re-evaluate its plans to obtain raw materials. The statement noted irregularities, lack of transparency mechanisms, and disregard for growing resistance by local communities, and called for the EC to implement policies that reduce consumption, promote recycling, and contribute “a fair share of support to the nations of the global South to redress the continued extraction of wealth from the global South for Europe, which has taken place for centuries."

Mining and extraction of natural resources for digital devices is unsustainable, and has led to massive violations of human rights, including the right to a healthy environment.

Within a linear economy, natural resources that are extracted and used in digital devices do not have value beyond the use of that digital device. A key objective of circular economies is to significantly reduce the extraction of natural resources through repair and recycling.

Learn more about mining and extraction in the circular world of digital devices through our case studies in Chapter 2.

Will this guide consider the impact of network devices and data centres?

This guide focuses on the personal devices that we use and touch – desktop computers, laptops, mobile phones and tablets. We know that these personal devices depend on network devices such as routers, and big data centres that deliver content and services. There is also an explosion of “smart” devices that create an “internet of things” (IoT). At least 20 billion new IoT devices are expected to be produced in 2020.

What is happening to electronic waste?

Electronic waste, or e-waste, is one of the fastest growing waste streams. E-waste is commonly discarded with general waste, leading to pollution of groundwater and other natural systems, and creating serious health impacts for local communities.

The fate of 82.6% of the electronic waste generated in 2019 is uncertain: mixed with other waste streams causing pollution, exported from high-income countries as second-hand products but still exported illegally for reuse or as scrap metal.

Countries in the global North continue to illegally export hazardous electronic waste to countries in the global South despite treaties such as the Basel Convention on Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal. Informal workers sort and process electronic waste for valuable minerals and resources. In 2019, the loss of secondary resources from electronic waste disposal was estimated to be valued at USD 57 billion.

Planned obsolescence – designing a product with an artificially limited useful life – is a huge barrier to the circularity of digital devices. In a capitalist society focused on infinite growth, durability of devices may be considered an enemy of profit.

Ecodesign initiatives are starting to define minimum requirements or ratings to promote durability and repairability of digital devices. The ability to upgrade digital devices with additional RAM (random access memory) and new batteries can significantly extend the useful life of a digital device, and make its computational power comparable to a new computer.

Projects that work towards circularity of digital devices also aim to reduce social inequality. Low-cost computing has become essential to overcome barriers to access to the internet, and social enterprises that repair and sell these devices provide employment opportunities for individuals that are interested in this work.

Learn more about social enterprises and projects to repair and recycle digital devices through our case studies in Chapter 2.

How do circular economies work for the planet?

Circular economies aim to keep resources in use for as long as possible, recovering and regenerating materials and products at the end of their “service life”.

Demand for low-cost computing for remote education has exploded in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, and advocacy for the “right to repair” is growing in many countries as there is growing recognition that repair and reuse of digital devices could be used to address critical shortages.

Circular economies of digital devices are declarations of interdependence. My computer or phone could have a life before me, or after me, and throughout its life that device interacts with the natural environment, upon which we all depend.

Circular economies recognise that we must design technology in ways that reduce environmental impact, increase energy efficiency, and enable recycling and reuse.

Reduce: Circular economies aim to reduce the negative impacts of digital devices by prolonging their useful life, reducing packaging, and re-designing the technology. The average lifespan of a digital device is affected by many factors, including the availability of software updates and replacement hardware, which are usually considered in the design process for product repairability and upgradeability.

Reuse: Often digital devices that appear to be at the “end of their life” are in fact only at the “end of their use”, and only need to be repaired, and their data cleaned, in order to extend their useful life. Reuse of digital devices is usually supported by online and physical “second-hand” markets, with or without a warranty.

Recycle: When a digital device can no longer be reused it can undergo a process of disassembly or separation of the parts – and subsequent extraction of valuable resources. Waste electronic equipment, including digital devices, is typically regulated by law.

What are the processes of a circular economy of digital devices?

A circular economy can be understood in terms of different processes in the life cycle of a digital device. These processes are interdependent and create new loops within the wider life cycle of a digital device. A laptop computer may go through several cycles of use, repair and reuse before it has reached the “end” of its life, at which point it may be disassembled, and its resources extracted.

Mining and extraction are considered the first process in the life cycle of a digital device. These devices often rely on minerals that were extracted in conditions of armed conflict and widespread human rights violations. Although many global initiatives are working to increase transparency and accountability within supply chains for minerals, many devices continue to be produced with “conflict minerals”.

Manufacturing for most major digital device brands is done by companies working in electronic manufacturing services (EMS), which design, manufacture, test, distribute, and offer return/repair services for the original equipment manufacturerer (OEM). Foxconn, a Taiwanese EMS company, manufactures parts and equipment for other companies such as Apple, Dell, Google, Huawei and Nintendo. These EMS companies have their own suppliers of printed circuit boards and electronics components. Human rights violations are a serious concern in many factories.

Sustainable public procurement means that public institutions only obtain goods and services that minimise the damaging effects on the environment and have been produced under humane working conditions. The buying power of major public customers can have significant economic weight and therefore a potential leverage with the supplier for sustainability issues.

Public institutions, directly or through purchasing consortiums, can have procurement contracts that include clauses to ensure compliance with environmental codes – e.g. ecodesign, life cycle assessment (LCA), quality recycling – as well as labour, safety and quality standards in the supply chains of the information and communications technology (ICT) hardware purchased.

Standards might include due diligence of suppliers regarding compliance with a set of requirements, and also requirements regarding take-back, further reuse, and responsibility for e-waste disposal by certified agents. In addition they may have cost supplements for good quality recycling that maximises resource recovery and minimises disposal and effects.

Public procurement must also consider compliance with the Core Conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO) in the production process, or whether energy efficiency demands are met.

Through their added negotiating power, purchasing consortiums can help to minimise environmental impact while improving the quality, cost efficiency and effectiveness of procurement processes and the verification of compliance.

The use, repair and reuse of digital devices depend on many factors. A device may be deemed no longer suitable for a task because the task requires more computing capacity, different functionality, or because the performance of the device degrades over time as it wears out. The software used on most devices evolves over time (e.g. bug and security fixes, new features), and some devices can also have upgraded hardware to adapt to evolving needs.

Due to the rapid evolution of digital electronics, specialised parts may no longer be manufactured, and so the supplier may be unable to provide spare parts to repair the device. The reuse process ends when the device or a component returns to the disposal state, which means its use value, even if improvements were made, does not allow for reuse again. This results in recycling, a process that transforms computational use value into raw material use value.

Recycling and management of electronic waste is considered a final process in the life cycle of a digital device, but within circular economies this process may also be the beginning of a new cycle, whereby components of the device are disassembled and used to create new digital technologies.

If we consider that devices are valuable for their computing resources, then we should focus on the right to use a device, not on the right to ownership. Maximising circularity asks us to see devices as collective property that circulates among users until they are finally recycled.

WHAT IS HAPPENING IN THE CIRCULAR WORLD OF DIGITAL DEVICES?

Mining and extraction

"We are struggling to survive": Resistance to mining in Acacoyagua, Chiapas

Written by: Jes Ciacci (Sursiendo)

Full text of this case study is available on our blog in English and Spanish.

In 2015, members of the local communities of Acacoyagua, Chiapas, Mexico created the peaceful citizens’ movement Frente Popular en Defensa del Soconusco (FPDS) in response to growing health and environmental impacts of mining and exploitation of gold, silver, lead, zinc, iron and titanium. Digital devices contain many of these minerals.

As of September 2019, the Ministry of Economy of Mexico has registered 140 open pit mines in Chiapas, with permits until 2060. A small mine consumes around 250,000 litres of water per hour while a large mine uses between one and three million litres per hour.

The first permits in Acacoyagua, Chiapas date back to 2012, although some members of the community in Acacoyagua remember noticing the arrival of mining companies as early as 2006. By 2015, rates of cancer, particularly liver cancer, became the leading cause of death in locality.

The most serious environmental consequence of the mining for the people of the region has been the contamination of the Cacaluta River, which provides water to the aquifiers and supplies water to the homes of Acacoyagua Municipality.

Fish began to die. Local communities could no longer feed on the mojarras, pygmy lobsters and sardines they once fished. Thus began the process of defending the territory, which today not only implies having declared the municipality free of mining but also questioning other forms of overexploitation of the territory, such as the existing agribusinesses in the area.

In an article published by Mongabay magazine, a delegate of the Secretary of the Environment (SEMARNAT) in Chiapas, Amado Ríos, indicates that the agency assumes that the Casas Viejas mine does not pollute because the minerals are not processed on-site.

The population of Acacoyagua experience in their own bodies the effects of the mining. Despite the social strength and knowledge about mining that have been acquired throughout their organisational process, to date it is still difficult to track down the investing companies involved. The state and national governments, in their different bodies, give each other the responsibility of having to provide reports. The result is a lack of data.

There is also no explanation as to why mining projects are allowed in nature reserve sites. The aforementioned article states that for the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, "the files of each concession can only be consulted by those who can prove their legal interest or through the General Law of Transparency and Access to Public Information."

The towns of Escuintla and Acacoyagua were the first to organise to resist the mining. Once the FPDS was formed, they joined the Mexican Network of People Affected by Mining (REMA) and since then have established different strategies for the defence of the territory, from direct actions, such as roadblocks, to information processes, assembly declarations and media and legal actions. Local public authorities and private security of the mining companies retaliated quickly, aiming to stop the social mobilisation. However, as one community member involved in the mobilisation stated, “We are defending our territory so that our children can continue to live as happily as we have in these places.”

In 2018 the communities lifted the roadblocks but maintain an active surveillance system in which people from the communities make their rounds on bicycles, and if they find a mining truck they immediately alert the other populations who come out to stop it.

A combination of strategies has made it possible to defend against mining. "People are happy now because they did see a very drastic change. We have a photo from 2019 with some river prawns from a meal they had in the mountains to welcome a journalist. People are beginning to see much more life in the river” (L. Díaz Vera, personal communication, 23 September 2020).

There are two fundamental dates for Acacoyagua that reaffirm the struggle. Every 20 June, on the anniversary of the organisational process, the community sings, performs dances, reads poetry, and makes announcements. In December, a large gathering is held in homage to the resistance with food, marimbas, raffles and a piñata.

Land and territory defenders in Latin America have a long history of implementing strategies to care for their lives and environments. The struggles have taken place in various dimensions but, as the story of Acacoyagua tells us, what has worked for them to stop the contamination has been a strong organisational process and non-violent direct actions.

In order to build future technologies that respond to the care of life, it is necessary to reconnect with other local, nearby consumption models that encourage diversity and connection with the people who produce them, that listen to the cycles of life (nature takes millions of years to produce minerals or oil), and designs that respond to these premises.

These other forms of development that respect the needs of local communities will also allow us to think of ways to relocate technologies, their production and circulation, to advance on open models of software and hardware development, to reduce consumption and diversify it, responding to localised problems and adding up to proposals based on care towards populations, communities and environments. Perhaps this is the technological development that would allow us to see a desired impact on the worlds we inhabit.

SMaRT innovation for urban mining

Written by Syed Kazi (Digital Empowerment Foundation)

Founded in 2008, the Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) at the University of New South Wales in Australia is conceptualising new ways to process complex waste.

Thermal micronising uses gases generated from the waste plastics within complex waste streams such as e-waste. The microfactory on the university’s campus has been producing plastic filaments for 3D printing extracted from electronic waste.

Design and manufacturing

Fairphone

Written by Leandro Navarro (UPC and Pangea)

Fairphone was founded with the intention to develop a mobile device that does not contain conflict minerals (which in smartphones are typically gold, tin, tantalum and tungsten), has fair labour conditions for the workforce along the supply chain, and can be repaired and upgraded to help people to use their phone longer.

As of 2020, the social enterprise has released three generations of the Fairphone, with more than 100,000 users. A special focus is the modular design of the device, which allows for easier repair. Fairphone 2 was the first smartphone to get a 10/10 score by iFixit for repairability. Across the different phases analysed in a life cycle assessment of Fairphone 3, the climate change impact, as measured by the global warming potential (GWP) of each phone, is estimated to be 39.5 kg CO2e.

Fairphone estimates that there is an average of 38 different materials in a smartphone, each with its own complex supply chain. Fairphone has a public map of first-tier assembly manufacturers and second-tier component suppliers.

Fairphone was the first smartphone company to incorporate fair trade gold in its supply chain, and over time the company is improving material sourcing, including more responsible mining practices, and increased use of recycled materials. The company estimates that approximately 32% of their eight “focus materials” have been sustainably sourced for the launch of Fairphone 3.

In 2018, Fairphone set up a pilot project with companies, asking them to pay a monthly fee for a package of phones, but the ownership remains in the hands of Fairphone and eventually the phones are returned to them.The intention behind maintaining ownership of the devices is to provide incentive to innovate design, and ensure that most resources are recoverable. The cost of the Fairphone 3 is more than USD 500 per device, indicating that more progress is needed for large-scale production of fairly produced and affordable devices.

Public procurement

Electronics Watch

Written by Peter Pawlicki (Electronics Watch)

Electronics Watch is an independent monitoring organisation providing public buyers with capabilities to monitor their supply chains and verify their suppliers’ compliance with social criteria they have set in contracts for ICT hardware.

Public buyers, such as universities, hospitals, counties, cities and other public institutions, buy large volumes of computers, servers, smartphones and printers. Multi-year contracts with electronics brands enable public buyers to leverage this relationship to address workers’ rights and environmental concerns in their supply chains.

Electronics Watch is a network of monitoring partners and of more than 330 public buyers in Europe. Monitoring partners are civil society organisations, located near workers' communities in production regions, who use the worker-driven methodology to monitor for labour rights risks and violations in factories.

Electronics Watch monitors have developed relationships of trust with workers, meeting with them in conditions that minimise their fear of reprisals. Workers therefore often report problems to them that they may not discuss with social auditors they may never have met before.

Labour rights violations in Thailand

In 2016, the Migrant Worker Rights Network (MWRN), an Electronics Watch monitoring partner, documented labour rights violations at Cal-Comp factories in Thailand. Subcontracted migrant workers from Myanmar at Cal-Comp’s two facilities in Thailand were at risk of forced labour through debt bondage and withheld documents. The debt bondage was linked to excessive recruitment fees.

At this time, Cal-Comp was a supplier of printers, external hard disk drives and other computer peripherals to brand companies like HP, Seagate, Western Digital and others. A high share of Cal-Comp’s workforce in Thailand were migrant workers from Myanmar, and Electronics Watch with MWRN documented a number of labour rights violations, including passports and other documents taken and withheld from workers, and excessive and unlawful recruitment fees equivalent to 30 to 90 days of workers’ wages.

Electronics Watch affiliates were actively involved throughout the process. Public buyers that had links to the Cal-Comp factories through products they procured, engaged directly with brand companies to ensure progress.

Electronics Watch learned that labour agents sought to coerce workers at Cal-Comp to lie to social auditors about their recruitment fees and related expenses. These agents threatened workers that buyers would pull their orders if workers reported their full costs in upcoming audits and that workers would, consequently, face dramatically reduced overtime or even lose their jobs.

After more than three years of investigations, monitoring and engagement with brand companies, the manufacturer and the Responsible Business Alliance (RBA), Electronics Watch, its affiliates and MWRN were able to achieve major improvements, including:

- Since 2017, migrant workers employed by Cal-Comp hold their own passports and work permits.

- In November 2019, Cal-Comp fully reimbursed at least 10,570 workers in the largest single company settlement of migrant worker recruitment fees ever.

- Cal-Comp has stopped hiring migrant workers until they have developed an ethical recruitment policy to ensure no worker pays for their job at Cal-Comp.

This case shows that the Electronics Watch model of worker-driven monitoring is essential to detect and address forced labour. MWRN’s rapport with workers, their everyday access to workers, and their ongoing careful recording of workers’ recruitment experiences were essential to understanding the full extent of the risks of forced labour and debt bondage that migrant workers face and to defining the full reimbursements and remediation they are owed.

Ongoing industry engagement by Electronics Watch, supported by affiliates’ communication with their suppliers, is central to remediating violations and improving working conditions.

Public procurement has a strong leverage with its supply chains that it can utilise to support sustainable improvements for workers and affected communities. To be able to drive positive change, public buyers need to be able to rely on independent monitoring for verification.

Use, repair and reuse

eReuse.org

Written by Leandro Navarro (UPC and Pangea)

Disposed digital devices (computers, tablets, mobiles) are a resource for local social inclusion and participation. The vision of eReuse.org is that public and private organisations can act for the common good by donating disposed devices to social enterprises that repair, refurbish and distribute these devices to families – enabling them to participate in education and socioeconomic activities in their communities.

The “second-hand” market for digital devices creates employment and feeds a circular economy that improves local socioeconomic and environmental conditions.

The eReuse.org project essentially consists of four elements:

- Collect, repair and refurbish digital devices for reuse, ensuring final recycling.

- Bootstrap collaborative local circular economy ecosystems across all stakeholders in the reuse and recycling of digital devices.

- Trace, certify and measure circularity of products, members and platforms.

- Coordinate the development of open-source tools for reusing electronics.

eReuse.org makes agreements with public and private donors of digital devices, social enterprises and social inclusion programmes working in repair, refurbishment and recycling, and social organisations working with end-users.

The key features of the eReuse strategy are:

- Data collection about circularity of devices (chain of custody).

- Data aggregation and analysis of impact: social (hours of computing use created) and environmental (CO2e savings).

- Repair and refurbishment training.

- Dissemination of information based on the results of data collection and analysis, including raising awareness about the environmental impact of digital devices.

The eReuse.org project began in 2013, and in 2015 the computer donation campaign was launched. As of September 2020, approximately 10,000 computers had been processed and supported through 10 to 20 active social organisations in three regions: Barcelona, Madrid and Bilbao.

The impact of the project includes:

- Reduction of electronic waste and environmental impact of digital devices.

- Significant increase in access to digital devices in three regions.

- Creation of jobs in computer refurbishment.

- Development of tools for more efficient processing of digital devices.

- Collection of reliable data to promote circularity and to quantify and certify impacts.

Computadores para Educar – Colombia

Written by Julian Casasbuenas G. and Plácido Silva (Colnodo)

The Computadores para Educar (CPE) programme, formally established in 2000, is a public entity approved by the Colombian National Council for Economic and Social Policy. CPE began as a programme of the Colombian government for the donation of computers by public entities and private companies to public schools and colleges in the country.

When the CPE programme first started, the donated computers were remanufactured and sent to educational entities. This strategy changed, and currently CPE only delivers new computers and tablets. The equipment that was initially remanufactured has remained in educational entities for an average of five years of use.

Repair Café

Written by Leandro Navarro (UPC and Pangea)

The Repair Café is a non-profit organisation that began as an idea in 2007 to build skills to repair digital devices. There are now 2,000 Repair Cafés in more than 24 countries. In 2017, over 300,000 digital devices were repaired.

Repair Café recognises that in many countries we throw away items with almost nothing wrong with them because we do not have the skills to repair them. Repair Cafés aim to involve people with repair skills to share their knowledge, enabling digital devices to have longer lives instead of being thrown away.

“Enter the Circle of Solidarity!”: A multistakeholder environmental campaign aimed at bringing ICT equipment to disadvantaged communities in Romania

Written by Rozi Bako (Strawberrynet)

Lack of access to the internet and ICT infrastructure is a systemic problem in Romania. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, unequal access to digital education infrastructure has enormous consequences.

The 2020 ECOTIC campaign is distributing refurbished ICT equipment to specific communities in Romania where access to the internet is low – focusing on schools and NGOs. The campaign was launched in June 2020 and ran until October, and is part of a broader waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) awareness campaign by ECOTIC in partnership with the Romanian Ministry of Environment, Water and Forests.

Computer Aid Solar Learning Lab

Written by Alejandro Espinosa (Computer Aid)

The Solar Learning Lab (SLL) is a standard used shipping container converted into a classroom, with 11 computer workstations operating off of a thin-client network (a low consumption network with a server) and powered by a connected solar power system. The first SLL was established in the village of Matcha in Zambia in 2011. In partnership with Dell Technologies the project expanded to Colombia and South Africa in 2015, and to Kenya, Sierra Leone, Morocco and Mexico by 2019. In total, Computer Aid has set up 32 Solar Learning Labs.

A shipping container structure provides a secure and innovative space that can be relocated, where brick and mortar infrastructure may be more difficult. However, depending on the location and context, there can be high logistics and transport costs to set up a Solar Learning Lab. The Computer Aid model for the SLL relies on support from donors and companies to deliver infrastructure, reusing shipping containers, and training programmes.

Computer Aid has learned that local ownership required adapting design features of the lab to the specific context, and creating a space that is not just a computer room but a local hub for the community. In Mexico we launched a new double design to offer a dedicated space for robotics practices in addition to the computer lab and in between the two labs we created a space to accommodate more learners with laptops.

In November 2020, Computer Aid will partner with Zenzeleni community network in the Eastern Cape of South Africa to set up a Solar Learning Lab. Together, ComputerAid and Zenzeleni will carry out a documented learning process to understand how community networks and Solar Learning Labs can support each other to increase their positive impact and their sustainability.

Club de Reparadores

Written by Florencia Roveri (Nodo TAU)

Club de Reparadores is an initiative launched in Argentina in November 2015 by the organisation Artículo 41. The intention of the initiative is to raise awareness of repair as a sustainable practice of responsible consumption, inspired by movements developed in other countries.

Club de Reparadores aims to promote the repair of objects, to extend the useful life of things, claim the culture of repair, and promote knowledge and abilities involved in repairing and care and closeness as a social value.

Recycling and management of electronic waste

Computer e-waste management in Rosario, Argentina: From scarcity to excess

Written by Florencia Roveri (Nodo TAU)

In 2010, Nodo TAU started to develop an e-waste management plant, reducing environmental impact and offering work, social and digital inclusion. The challenges addressed were to recover and repair unused computers for reducing e-waste and devices kept unused in houses, institutions, private companies and government offices, while developing a sustainable enterprise with decent work conditions that offers job opportunities and providing devices to digitally excluded groups.

Nodo TAU is a civil association founded in 1995 by a group of engineers to work on the promotion of ICT for social – mainly grassroots – organisations, to address the digital divide. From 2003 to 2008, Nodo TAU developed a network of community telecentres together with the coordination of territorial organisations. Nodo TAU promoted the reception of discarded computers to be reconditioned in a “Bank of Machines” where they received the donations to be repaired.

Machines that cannot be repaired

Donations of used digital devices started slowly, coming from individuals and small companies. As time passed, the quantity of devices became unmanageable for the organisation, implying risks for people working in Nodo TAU and in the house shared with other organisations.

The problem became more evident when, in 2007, Nodo TAU received numerous donations of computers from a multinational agro-industrial corporation, which included modern notebooks that allowed the development of a mobile digital classroom (Aula Digital) for workshops in communities. The donation also included a large amount of machines that could not be repaired. Facing the problem of e-waste accumulation, Nodo TAU started to deepen its work on local circuits of recycling and to develop resources for addressing e-waste management.

An educational pilot project

In 2008, the Secretariat of Environment and Public Space invited Nodo TAU to join a project for the development of an e-waste recycling plant, together with Taller Ecologista, the main environmental organisation of the city, and the National Institute of Industrial Technologies (INTI).

As a result of this discussion, in 2009 Nodo TU developed an educational pilot project, consisting of the coordination of workshops on repairing computers with young people from poor neighbourhoods, together with the municipal Secretariats of Social Economy and of Environment in charge of the provision of the collected devices.

In 2012, the pilot project became an enterprise named “Reciclados Electrónicos”, promoted by the municipal government. Development of the plant was delayed due to internal conflicts in the municipal government.

In 2016, with support from APC, Nodo TAU developed a study of the local market and holders of e-waste treatment facilities, developing a business model for the functioning of the plant. This included collaboration with Barcelona-based APC member Pangea to implement the traceability system developed by the eReuse.org initiative. However due to internal conflicts in municipal government, the project of the plant was stopped.

New opportunities

Nodo TAU is now working with a close grassroots organisation, Grupo Obispo Angelelli, who invited Nodo TAU to join projects aimed at job inclusion for young people in the context of the provincial social programme Nueva Oportunidad (New Opportunity) in 2019.

In 2019, a provincial law was approved that regulated the management of e-waste, including extended responsibility and recognising the social repairers as a stakeholder. Furthermore, Nodo TAU has found an adequate place to install the plant that complies with all the formal requirements for functioning, and has started operations. A key factor in its implementation and sustainability was the inclusion of the plant in the Nueva Oportunidad programme.

In 2020, a new source of devices started to arrive at the plant: netbooks from the educational programme Conectar Igualdad, which distributed five million computers from 2010 to 2015 among students of public high schools. When the programme was discontinued, large amounts of computers were left unused, piled up in schools due to problems of poor maintenance. When the COVID-19 pandemic forced schools to lose and education turned to digital platforms, these unused computers became fundamental for students.

In September 2020, the provincial Ministry of Education signed an agreement with Nodo TAU for the repair and upgrade of computers, working in coordination with the authorities of each school.

E-waste and employment in the region

During 2019, Nodo TAU was invited by the ILO to participate in a research project about e-waste and employment in different countries of the region, starting with a pilot in Peru and Argentina. The project involved the reconstruction of the value chain, involving the organisation of local roundtables for discussion among relevant actors.

In 2020, the work with the ILO followed a second period dedicated to research on the management of electronic waste from the circular economy perspective. Research will be followed by capacity building in the field.

Sustaining and scaling electronic waste management

The sustainability of the project depends on the public programmes and policies in which it participates. With the support of the provincial government, the project offers scholarships for young people training and working in the plant, guaranteeing a stable income for them. The process is always evolving and allowing new scenarios, generating allies that strengthen the work, mainly in reference to the stability of workers involved in the plant.

More recently, coordination with the local office of the ILO to develop research work provides relationships with local companies, unions, municipal governments of the region and different areas of government, that also contributes to the growth, dissemination and potential replicability of the experience. This could be mentioned as a good practice of the experience. Scalability is being addressed as a key objective at this moment.

Karo Sambhav

Written by Syed Kazi (Digital Empowerment Foundation)

Karo Sambhav is a producer responsibility organisation (PRO), collaborating with enterprises in India to design and implement extended producer responsibility (EPR) programmes for electronic waste. Extended producer responsibility requires producers of digital devices to be made responsible for the full life cycle of that device, particularly at the end of its life. Karo Sambhav works with producers and manufacturing companies like Apple, Dell, HP, Lenovo and Toshiba to implement their EPR obligations.

Karo Sambhav focuses on raising awareness, building capacity and exchanging knowledge among the e-waste sector in India. The objective of this collaboration is to address critical gaps in the market and develop a locally relevant ecosystem for responsible collection and recycling of e-waste with the end goal of mobilising private sector investment towards the industry.

Karo Sambhav’s India E-waste Programme was launched in 2017 in partnership with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which is part of the World Bank Group. As of October 2020, Karo Sambhav provides services across 29 states and three union territories of India. In the first two years of the programme, Karo Sambhav has successfully collected and sent over 6,000 metric tonnes of e-waste for responsible recycling.

Karo Sambhav’s school programme is important in implementing behaviour changes. The school programme was run in 40 cities across 29 states and two union territories. More than 1,500 schools participated in the programme in the 2017-2018 session.

Karo Sambhav’s e-waste programme has created channels with stakeholders across the value chain, including consumers, bulk consumers, waste pickers and aggregators. It is also working with retail and repair shops to help them build sustainable and legal ways to dispose electronic waste. Since 2017, Karo Sambhav has engaged more than 800 repair shops, 500 bulk consumers, 5000 waste collectors, and 600,000 individuals across India.

Sustaining and scaling electronic waste management

Karo Sambhav’s e-waste programme has proven to be sustainable in terms of bringing a circular approach of ICT. All five programmes of Karo Sambhav have yielded positive results and it has proved to be sustainable in terms of scalability and replicability.

The current biggest challenge for Karo Sambhav is that producers and recyclers are not fully convinced of the role of a producer responsibility organisation.

Informal markets for electronic waste also pose a challenge for Karo Sambhav, as they offer lower prices for e-waste collection and management.

Karo Sambhav programmes are present across India, and are contributing to a circular economy, starting from partnering with producers and engaging with recyclers. The aim of these partnerships is to enable an ecosystem for electronic waste recycling and management that is based on circular economy models and is sustainable at all levels.

Youth involvement in sustainable management of electronic waste in the DRC

Written by Patience Luyeye

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has no specific legislative framework for the management of electronic waste in the country. In this context, Benelux Afro Center (BAC), a non-profit organisation created in 1998, set up the first small-scale electronic waste collection and management services in Kinshasa in 2013.

In 2016, a project was funded for the collection of waste in the province of Kongo Central because of the large amount of waste that importers store around the port. E-waste is sent to a technical school in which students have been trained to recycle and manage electronic waste.

E-waste management stations were set up in Kisantu, Mbanza Ngungu, Matadi, Boma and Muanda, managed entirely by young people. This project made it possible to collect and treat 13,500 kg of WEEE in 2017, and give work to at least 10 young people at the various relay stations and three young people permanently at the Matadi workshop along with around 10 occasional day workers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This preview of a guide to circular economies of digital devices was developed by the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) network, led by Leandro Navarro (UPC and Pangea), Syed Kazi (Digital Empowerment Foundation) and Shawna Finnegan (APC). The guide was edited by Mike Jensen and proofread by Lori Nordstrom. All visuals were designed by Cathy Chen.

Case studies were developed by Jes Ciacci (Sursiendo), Florencia Roveri (Nodo TAU), Peter Pawlicki (Electronics Watch), Alejandro Espinosa (Computer Aid), Patience Luyeye, Rozi Bakó (Strawberrynet), Julián Casasbuenas and Plácido Silva (Colnodo), Syed Kazi (Digital Empowerment Foundation), and Leandro Navarro (UPC and Pangea).

A working group of APC members, partners and staff are supporting the development of the guide.

CONTACT US

Please contact us by email to share your feedback on the preview of this guide, and to share any case studies or stories!

Email: circular-guide@apc.org