Can artificial intelligence be ‘creative’? Can it be original? Can it make art, or music, or literature that is as meaningful as art of music or literature that’s made by humans? Can it understand emotion as well as we do?

Recent developments in artificial intelligence have brought those questions to the fore, for two reasons in particular, one technical, one human.

Go, go, go!

It used to be said that AI couldn’t be creative because everything it made came from the code with which we humans had enabled it. Machine learning’s flipped the lid on that because it enables computers to learn from data without explicit programming, ‘becoming their own teachers’ one might say.

When DeepMind’s AlphaGo beat the world’s top players of the fiendishly complex game called Go, it did so because its own insights showed it a better way of play than any human had envisaged.

Stay, stay, stay?

Arguments about the risk that human jobs are being lost through digitalisation often focus hope on the idea that there are some things humans will always be able to do better than machines. Culture and creativity are usually high up on that list. And one reason for that is that, it’s assumed, machines can’t understand or properly express human emotions.

This has been increasingly explored by both creative artists and computer scientists. Two major novelists, for instance, have looked at it of late from different viewpoints.

-

Kazuo Ishiguro’s Karla and the Sun, about which I wrote recently, focuses on the limited ability of his “artificial friend” to understand emotions and act appropriately on them.

-

Iain McEwan’s physically hyper-human, super-intelligent Adam, in Machines Like Me, writes (poor) haiku (short poems) but can’t cope with the nuanced and creative ways that people deal with partial knowledge and conflicts of interest.

Ada Lovelace and Marcus du Sautoy

The mathematician Marcus du Sautoy has also been exploring AI creativity, in a book, The Creativity Code, and, more accessibly, in public lectures. He riffs on Alan Turing’s famous test of computing capabilities – can a computer make a human think it is a human? – by posing another test he names after the nineteenth-century mathematician Ada Lovelace – can a computer originate a creative work of art (that is, one whose production can’t be explained by code or passed off as the work of coder)?

The fun part of du Sautoy’s lectures comes when he shows his audience some works of art, music and writing which have been produced through AI, compares them with those produced by humans, and asks the audience to work out which is which.

In most cases, in this version of the Turing test, so far, the majority usually gets the answer right but the margin’s often relatively small – 60/40 or thereabouts – and many are unsure. Already, in other words, computer-generated ‘art’ looks little different for most of us from the majority of ‘art’ we see about us.

Where are the limits?

There are limits to this, naturally. Du Sautoy’s examples suggest that AI’s ability to mimic human creativity is, at present, far more effective in some forms than others – in short forms like poetry, for instance, rather than in stories. His AI Rembrandt’s obviously not a Rembrandt (to those who know their Rembrandts) because it’s based on what’s similar in lots of Rembrandts rather than the insight into personality that made each of his portraits so distinctive.

But that may be simply down to the scale of data sets required. Already, AI ‘journalists’ are writing news reports on relatively simple subjects, such as sports results or company accounts. Machine learning’s likely to expand their range of writing skills. George Orwell predicted computer-generated novels, for the mass market, in his novel 1984 (published in 1948). Who’ll set the ethics for computer-generated journalism?

I’ll raise two questions here and then pose two further concerns on which I differ from du Sautoy.

What is creative?

Question one concerns the question “what’s creative?”

The distinction’s often drawn between what’s seen as the inherent ‘creativity’ of the human mind – people making something new through their imagination – and what’s seen as the inherent characteristic of machine intelligence – ‘creating’ something out of massive data sets.

But that’s not as different as it seems. Most human creativity is also based on algorithms and data sets. We just acquire and use them differently.

Music relies on rules, some of which are scientific, some of which are cultural. Art’s dependent on the ways that lines and colours interact and on the ways that people visualise them, some scientific and some cultural as well. Literature depends on language and the experience of both writers and readers: more rules, more norms.

Creative artists rely on their own databases when they make their art, music or literature – the things they’ve learnt at school and college, the art, music and literature with which they are familiar, what generations of past artists have created. Those of us who consume their work (read, look, watch, listen) do so within the framework of everything that we’ve read, seen, watched or previously heard. How different’s that from what is being done by AlphaGo?

What is creative innovation?

Much writing about this also compares AI’s potential with the work of genius, not the mundane. When Marcus du Sautoy asks us to compare an artist with an AI posing as that artist, he chooses one of the greatest of all artists (Rembrandt) rather than a run-of-the-mill portraitist. In music, he might have chosen Mozart.

But genius is rare. Creative innovators like Rembrandt or Picasso, Mozart or Stravinsky, moved the accepted rules of their creative discipline on to another level, in much the same way AlphaGo moved on the rules of Go. They could reach beyond the boundaries of previous artistry because they understand those boundaries well enough to do so. We could understand what they were doing because we also knew what boundaries they broke.

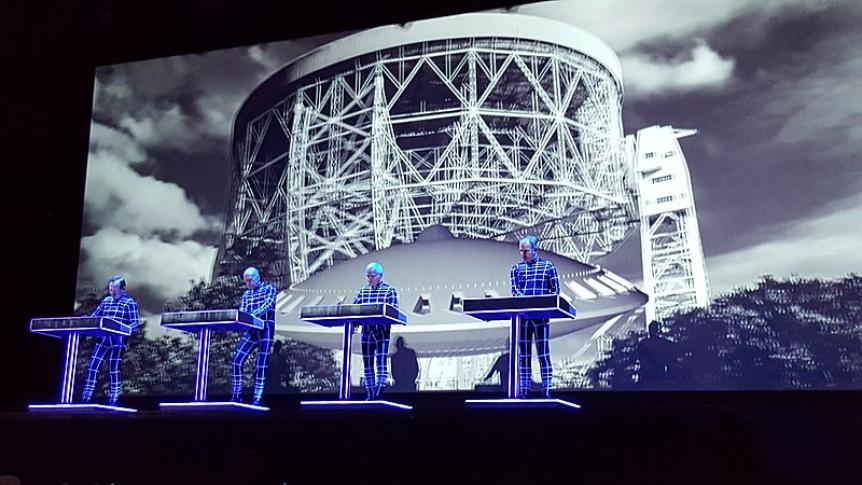

There is, of course, a history of hybridising technology with creativity. Music’s performed live, outside of lockdowns, but most recorded music’s been assembled in the studio by engineers for decades. Hybridising’s sometimes produced work that’s immensely creative and innovative (for the fun of it here are Kraftwerk playing live and David Hockney's drawings on an iPad).

More often, it’s been less imaginative. Most creative art, after all, is not intended to be innovative. Most music’s intended to respond to emotions that are widely felt, to provide a background soundtrack to our lives and conversations, to be heard (in shops, in lifts, in the background) rather than to be listened to, to be – this word’s important – subliminal, to influence or affect us without our being conscious that it’s doing so.

AI’s likely to be able to make muzak even if it can’t make music that’s more innovative. Much the same is true of art and design that are intended to provide the background to our lives rather than to challenge us – and for much of our lives that comfort zone is what we want and need.

Cultural diversity

The first of my two further concerns – beyond those inherent in what is above – is to do with cultural diversity. Cultural biases are inherent in most data sets. Machine learning that relies on data sets that are not representative tends to bring about discriminatory outcomes. We already know this and data scientists are trying to find ways around it.

Recommendation algorithms can be tweaked to reduce or increase the diversity of content to which users (readers, viewers, listeners) are exposed.

Much has been written about the risk that this will narrow people’s cultural experience. That’s possible, but so’s the risk that cultural experience will be directed by commercial or other intermediaries, that the tweaking will be in the tweaker’s interest not that of the tweaked. What’s the potential impact of this on minority cultures, or on new creative artists looking for an audience?

The risk of manipulation

My second further concern here’s therefore about manipulation of the audience.

We’re already familiar with the risk of deepfakes – videos that are manipulated to deceive their audience by those who make them, for purposes that range from ridicule through pornography and fraud to commercial manipulation and political disinformation.

Apps that can be used to ‘put one face in place of another’ are now being widely advertised. They can be fun, their makers say; they can be ‘creative’. And, of course, they can be dangerous, enabling harassment, falsifying political narratives and manipulating the decisions people make.

One of du Sautoy’s examples of AI-generated art is of abstract images that have been designed by a pair of algorithms with different parameters: one based on understanding existing artworks, the other on understanding people’s emotional responses to those artworks. Bringing these together means that artworks can be created that are more attractive because they respond to those emotional responses.

That also raises, though, the risk that powerful interests could manipulate content to influence emotions in ways that suit their commercial and political interests. The last few years have shown how effectively distorted information has been used to manipulate both personal choices and political outcomes, adding untransparent digital dimensions to longstanding experience in advertising (both public and highly targeted), marketing and political engagement.

Du Sautoy thinks this risk can be mitigated through greater digital literacy – enabling individuals to identify more clearly when they’re open to manipulation. Experience so far suggests that is naive. Those who seek to manipulate emotions, opinions and behaviour have far more resources, expertise and time available to do so than hard-pressed citizens just looking for a spot of relaxation. The most powerful and most dangerous manipulation isn’t that which is transparent, but that which is invisible.

Image: Kraftwerk at Bluedot Festival 2019, on Wikimedia Commons

Read also: 2019 Global Information Society Watch on Artificial Intelligence: Human rights, social justice and development