Facebook’s in the news again. Even more than usual. Whistleblowers are challenging its commitments to protecting users. Governments are threatening to regulate. And Mark Zuckerberg’s announced a change of name to Meta (‘beyond’ in Greek) and a change of goal from 2D social media to a 3D ‘metaverse’.

A personal disclaimer

I should say I’m not a Facebook user. Never have been, bar one time that an academic conference made Facebook the only way of talking to participants.

This isn’t ideology. It’s just not the way I choose to interact with people, or to entertain myself when seeking a distraction. I’m entirely happy that my family and friends make use of it, but it’s not the internet and not my vision of reality.

I’ve often been critical of Facebook – for the way that it exploits personal data, the impact of its business model and its business practices, the risks associated with any media business having so much scope to influence behaviour – but I was also relatively generous on this blog when Mark Zuckerberg published thoughts about responsibilities that go with power.

What is this ‘metaverse’?

And so what is this ‘metaverse’? It’s not entirely new but it’s been given a big boost forward by Facebook’s announcement.

Zuckerberg calls it ‘the embodied internet’. The opportunity for each and every one of us to put ourselves in a space of our own making, which we can fashion round what we think “beautiful”, where we can “hang out” with anyone we want, which can embrace us as we work and play (and maybe as we rest). Where we can do things that will make us more productive and enrich our lives.

An artificial world or worlds of our own making to add further dimensions to our lives. Spaces that combine real and virtual realities. Augmented realities. That at least’s the vision.

We may need clunky headsets for the moment, but in time we’ll have “cool” glasses that look like the spectacles I’ve worn since childhood, but will also pull up holograms that visualise our projects in 3D and let us join our buds at gigs across the world.

The avatars that we can make may be amateur right now, but in time they’ll be photorealistic video, down to the smallest pores and tiniest of movements. We’ll find it hard to tell the virtual from the real. Or so it’s said.

Zuckerberg explains all this, with bright enthusiastic buddies, in a video, in which they call it, often, “cool” and “awesome”, enthuse about how (they think) it’s going to “monetise” a “creator economy” and make the world not only better but more “fun”.

Should we embrace, or mock, or fear this vision?

And so my question is: how should we feel about this?

It’s easy to be cynical about the video. Mark and his buddies’ avatars look less like modern IT pros than characters from pre-school cartoon shows I watched with my kids twenty years ago. “Beyond the universe,” if that’s what’s meant by ‘metaverse’, sounds to me a bit too much like Buzz Lightyear’s catchphrase in Toy Story, (“to infinity and beyond”).

But that does not exaggerate the vision in the video that much. Many commentators have compared it not with Toy Story but with a different film, The Matrix, a much more dystopian virtual environment in which the worlds people experience are digital constructs, not physical realities.

Are we heading for this metaverse?

Zuckerberg thinks so, or at least hopes so. His pitch is: this should be the new reality. He’s bet the company and changed its name according to his bet.

It isn’t just the future that he wants to bring about, but a future that he thinks is right and more or less inevitable. Other companies are keen as well. He says he wants them all to work together, to build the necessary infrastructure, agree the necessary standards – and, oh yes, to ‘build in safeguards from the start’ (on which more later).

Time for another disclaimer, I think, lest what I’ve next to say sounds anti-tech.

I think that virtual reality and augmented reality have very much to offer. I’ve seen examples, from pioneers, of the ways that they can visualise experiences, add new dimensions to education, help people overcome difficulties caused by disability and distress, enable scientists in other fields to advance understanding and identify ways forward.

There’s much to gain from them. What I don’t like’s the idea that virtual reality’s a better way of looking at the world than physical reality. Why not?

Let’s start by looking at the real world

We’ve just seen COP-26, at best, inch forward on the climate crisis. If there’s one area where technology’s most needed, it lies there: in finding ways to limit carbon use and carbon impact, and to mitigate the impacts of what’s gone before. New technologies should heads-up carbon impact.

We’re still in the COVID-19 crisis, which has put sustainable development – the world’s agreed priority – behind its schedule. We see around us worsening geopolitics, growing authoritarianism and the weakening of human rights. Devastating conflicts are underway in several countries, at least two of which face major humanitarian crises. Economic, social and digital divides are growing, even before the climate crisis hits its hardest.

Some, myself included, would argue these are the priorities for technological investment. But my main point here’s more philosophical.

It’s that the option of retreating into virtual worlds – worlds of our own making in which we can do whatever we want with whoever we want – is likely to make those of us who can afford it less likely to focus on the real-world problems that confront us. We can escape them, or feel we are escaping, rather than put in the time and effort needed to address them.

And then at digital experience

Opportunities and risks are more balanced in most people’s visions of technology today than they were ten years ago. We’ve more experience of the ways in which digitalisation can be used to harm and to exploit as well as ways in which they can advance prosperity and welfare.

There’s a nod to this in Facebook/Meta’s video. ‘Privacy and safety,’ says Zuckerberg, should be built in from the start – though Facebook’s record on these is, to say the least, not great and no suggestion’s given as to how they’ll be built in beyond involving ‘human rights and civil rights communities.’

That nod, though, is uncritical. The metaverse, says Mark, ‘will be good for the environment.’ Why’s that, you ask? Because people who’re connecting in its virtual spaces, through their headsets or smart glasses, won’t want or need to fly, he says. No mention’s made of the environmental costs associated with the hyper-connectivity required: to make the kit, to build the infrastructure, to share the data that will make it possible. Has Facebook modelled this? No evidence is shown.

The video, as I’m sure its author would acknowledge, is essentially PR. It’s making a pitch; about the upsides, not the downsides. And it’s seeking to revitalise a brand that has lost much of its sheen by making it about a ("cool" and "awesome") future rather than the (less cool, less awesome) past or (tainted) present.

But, as we should with all commercial pitches, especially those built on untried but powerful technologies, we need to think about what could go wrong as well as right.

Space is limited, so I’ll give five examples about why we need to focus on the ethics and potential outcomes here, and not just take the word of the enthusiast.

Reasons to be careful

First, think about equality. In our debates about the digital society we’re preoccupied with digital divides, and the development divides that they exacerbate. Now think about the infrastructure needed for the metaverse: where it will be and who’ll be able to afford it. Think about how inequitably COVID vaccines have been distributed this past year. And then about what that suggests the metaverse might do to power structures and (in)equality.

Second, think about the nature of experience. Facebook/Meta claims that our experience in the metaverse will be richer than it is in our reality today. Two examples.

When we’re at concerts, Mark suggests, we’ll be able to share the experience with holograms of chums from other continents, like sharing interactive games. But there’s a difference between gigs and games. The point of concerts (or of sports events) is being in the moment, live with the performers, and the crowd around us. That’s what makes them work for us as people, not being in a bubble with our virtual mates.

And we’ll be able, so we’re told, to visit ancient Rome and see what living there was like. But this is virtual reality, not time travel. Which historian’s view of Rome will this be? Which Roman’s experience – that of Caesar or a slave? Think about the politics of this with something that’s more recent, like enslavement in the southern USA. Or this year's insurrection at the Capitol. Who's going to write the virtual narrative?

Think, third, of privacy and safety. The issues here have been self-evident with what's here called the ‘2D’ internet for years, and Facebook’s record’s not alone in being far from good. The metaverse means far more data, more shared, more monetised.

And what of those smart specs that it’s envisaged that we’ll wear. The ones that can take pictures and videos without consent or knowledge from their subjects (and then remake them into holograms and manipulate them?). That can project images before our eyes while we are doing other things … driving, or looking after children, making decisions that affect the lives of others.

What is the chance of exploitation? Real world problems won’t disappear in virtual worlds, though the norms and social conventions round them may well be different (as they’ve been on social media). Workplaces in the metaverse will remain unequal, there’ll still be discrimination, women are still going to be harassed;. Cybercrime is hardly going to be absent.

And, finally, to politics. Given our experience with social media, how do we think the metaverse will interact with political dynamics – whether that’s the spread of conspiracies like QAnon or the management of opinion and behaviour by authoritarian regimes?

I raise these problems not because they are insuperable, but because we’ve learnt they’re too important to ignore. Not because there aren’t attractions to experimenting with alternatives in virtual reality, but because the upsides of technology are accompanied always by downsides; and because what we fear matters quite as much as what we want. Because it's better to think about what we might be getting into before we're getting into it.

Thinking about the metaverse

Facebook’s vision of the metaverse – Meta’s vision, if you wish – is that it’s the next generation on from internet, a ‘gamechanger’ (perhaps it should be called the ‘metanet’). And Facebook’s goal’s to play the leading role in that: whether it is ‘monetising the creative economy’ or providing the leading platform over which it rides. A commercial reinvention, then.

Is a metaverse like this inevitable? Or are there other, less pervasive, ways in which advanced technologies like VR and AR can be used – ways that are, to use the words of WSIS, more ‘people-centred, inclusive and development-oriented’, shaped by the needs of the world we have rather than imaginary worlds we hope for? Ways that pay more attention to human rights and environmental sustainability, that address the real world problems that surround us, that reflect the risks as well as opportunities, what we think would be ‘awful’ as well as what we might think might be ‘awesome’.

In conclusion

This column began its life Inside the Information Society. Some years ago it changed to be Inside the Digital Society. Call me old-fashioned if you will, but I’ve not keen to be Inside the Metaverse.

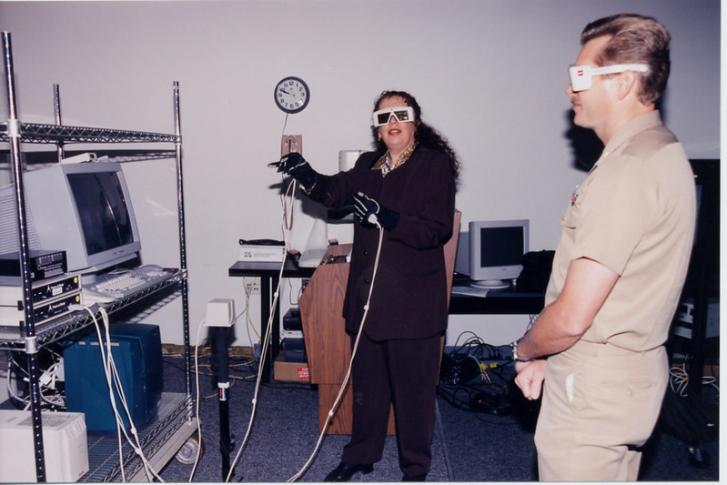

Image: Virtual Reality Demo by Uniformed Services University via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).