This week’s post looks at UNESCO’s current consultation on indicators for ‘Internet universality’.

The Information Society is built on data. Strange, then, that we’ve so much difficulty measuring what’s going on and where we’re heading.

What do we need to measure – and why?

The challenge here’s that we want to measure everything because, we think, the Information Society is changing everything. And, if/where it’s not changing things, we need to know that too.

If we measure more, measure well and analyse effectively, we’ll be better placed to make policy choices that suit our needs. We won’t necessarily make good choices, but the chances will be higher.

If we don’t measure well or analyse, we’re more vulnerable to misreading trends in our societies and to policy choices being made by those with vested interests to pursue. Evidence-based policy-making is about democracy as well as quality of governance.

So what’s the problem?

I’d suggest it’s fourfold.

First, for many things we simply don’t have numbers. National statistical offices are weak in many countries; household surveys rare. Next week, I’ll discuss insights from household surveys recently concluded in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Second, where numbers are available, they’re concerned with inputs not with impacts: with the devices and services that people have, not what they do with them and what happens as a result. If we want to know how our society is changing, it’s the latter that we need to know about.

Third, where data are available, they’re out of date soon after they are published. Things change quickly in the Information Society. Policy decisions need to be based on an understanding of where we are and where we’re going, rather than on where we were. Too many are being made on understandings and misunderstandings of the past.

And fourth, a lot of what we need to know’s not quantifiable. We’re learning the limits even of ‘big data’ – another future topic – but to grasp the Information Society as a whole we also need to understand the quality of change. We can’t reduce life to statistics.

UNESCO’s Internet Universality indicators

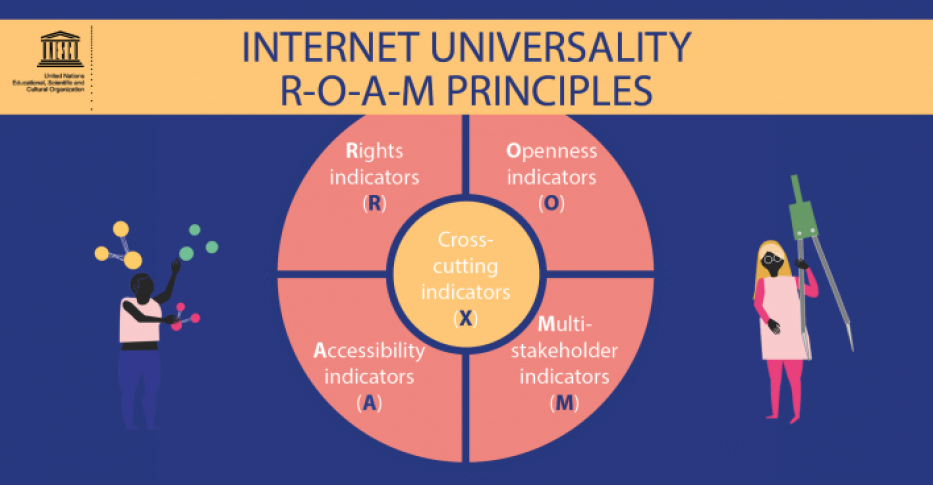

UNESCO’s Internet Universality concept is one attempt to widen ways in which we look at what is happening. It’s built around four themes of Internet development, its ‘ROAM principles’ – rights, openness, access and multistakeholder participation. That’s by no means everything about the Internet, let alone the Information Society, but it’s the range of themes on which UNESCO advocates.

It’s looking to develop indicators for those principles. Draft indicators have been published, following a general consultation. Full disclosure here. APC is working with UNESCO on these indicators, and I’m working with them both as lead researcher.

The draft indicators build on a successful model: UNESCO’s experience with its indicators for media development. They’re open for consultation until 15 March 2018. Everyone’s invited to comment, and everyone who wants should do so. Three questions:

- What do you think should be added (or removed)?

- What suggestions do you have for alternatives to indicators that are currently proposed?

- What sources would you recommend to verify the indicators that are used?

The purpose of UNESCO’s indicators

The purpose of these indicators matters. They’re not intended to draw league tables ranking countries.

The aim is to help governments and other stakeholders to understand the Internet environment they’re working with, and develop policies that will enhance those four UNESCO principles – maintaining and improving rights, openness, access and participation online – and so contribute to broader international goals that include sustainable development and gender equity.

And to achieve that, it’s necessary to understand both context and complexity. If you want to rank countries, then you need a simple index that uses just a few key indicators. But if you want to know what’s happening inside countries, you need a collage of evidence of different kinds from different sources. Not just what can be quantified, but also qualitative evidence, including considered judgements of the legal and regulatory frameworks that are in place and how they’re working.

The structure of the indicators

The draft indicators for Internet Universality use UNESCO’s media indicators as a model in order to build that collage. They’re in five categories. Each includes the relevant policy and legal framework, and specific themes relating to that category:

- Rights indicators, including freedoms of expression and association, privacy, the rights to information and participate in public life, and social, economic and cultural rights.

- Indicators of openness, concerned with open standards, markets, content and data.

- Accessibility to all, including connectivity and usage, affordability, equitable access, content and language, capabilities and competencies.

- Indicators of multistakeholder participation at national and international levels.

- And cross-cutting indicators concerned with gender, children and young people, sustainable development, trust and security, and legal and ethical aspects of the Internet.

Around these, there’s a sixth group concerned with the context in which national findings must be understood and national policies developed – economic and demographic indicators, and those concerned with development, equality, governance and the overall state of ICT deployment.

For each of the themes within each category, the indicator framework asks a number of questions and suggests the indicators that can be used for their assessment. Over a hundred questions all in all – some quantitative but many qualitative – intended to build up the collage of understanding that’s needed if evidence-based policy is to be made.

Process matters here, as well as evidence

It’s not just having data that’s important here. It’s going through the exercise – the process – of data gathering and analysis.

It’s been too easy for governments and other stakeholders to make glib judgements about the likely impact or value of Information Society developments when they don’t have a lot of data or don’t feel the need to gather evidence and think about it. There’s political (and other) advantage that can be made by vested interests exaggerating opportunities and threats.

The risk that poor policy choices will be made’s reduced, not just by having evidence but by being forced to think about what where that evidence is pointing. The value of a framework like that UNESCO’s here proposing is that it encourages governments and other stakeholders to think more thoroughly and more comprehensively before they act.

The challenge of the indicators

Two final points, which apply not just to this indicator framework but to other efforts to gather information on how the Information Society’s developing.

There’s a balancing act in any indicator framework. It’s important to build as strong an evidence base as possible, but it’s important, too, that the wish to be comprehensive doesn’t make it impossible for those using the indicators to do the job.

Resources are limited. You can’t gather information about everything. What matters is that an investigation should be feasible with resources that can be made available in most countries – and that it should be built around evidence that can be gathered credibly and reliably. The right number of indicators is not the largest number or the smallest, but what’s both necessary and feasible.

And it’s important not to confuse data-gathering and analysis with advocacy. The purpose of the indicators is to find out what is happening – where we stand today and what are current trends. To inform decision-making, not to justify it. If there’s agreement on the evidence, then policy debates are much more likely to lead to outcomes that will have general consent. One reason for urging multistakeholder participation in data-gathering and analysis is to ensure they’re not distorted to favour outcomes that will suit some groups within society.

In conclusion

UNESCO’s draft indicators are open for consultation until mid-March. Contributions are invited, welcomed and will matter. Take a look and have your say.