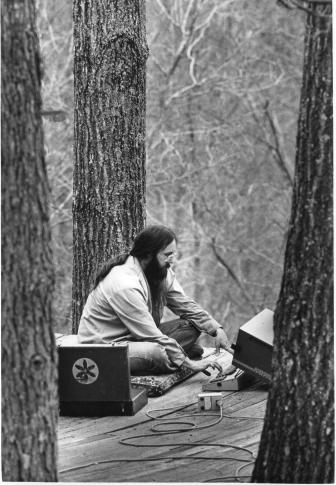

Albert K. Bates works on a Kaypro-10 computer from his home at The Farm in Summertown Tennessee, 1981. Source: Wikimedia CommonsEach week David Souter comments on an important issue for APC members and others concerned about the Information Society. This week’s blog is the first of two about the impact of ICTs on the environment. See part II here .

Albert K. Bates works on a Kaypro-10 computer from his home at The Farm in Summertown Tennessee, 1981. Source: Wikimedia CommonsEach week David Souter comments on an important issue for APC members and others concerned about the Information Society. This week’s blog is the first of two about the impact of ICTs on the environment. See part II here .

Climate change, many feel, is the biggest challenge facing the planet. It’s also the central question of sustainable development: how do we enable economic prosperity and improvements in the quality of life, for a growing population, while reducing fossil fuel consumption?

The ICT sector is the biggest game-changer there’s been since sustainable development became a core goal of the United Nations in the 1990s. As I argued in an earlier post, it’s changing the underlying structures of economy, society and culture; and so it’s changing the ways in which sustainable development can be approached.

So what’s its impact been (and what will it be) on climate change? Most significantly, what’s it been (and what will it be) on energy consumption and efficiency – and thereby on the fossil fuels that supply most of our energy requirements?

It depends on what you’re looking at

There are two ways of looking at this (or maybe three – see later). We can start with the energy that is consumed by the ICT sector – in making ICT equipment, running ICT networks and data centres, using devices, automating systems. The Forum for the Future and others have called these ‘first order’ or direct effects.

Or we can start with the energy that might be saved by the efficiencies that ICTs enable – by making transport and machinery less wasteful, heating houses only when they need it, turning commuters into telecommuters, and so on. The Forum for the Future (and others) have called these ‘second order’ or indirect effects.

Both types of impact have been analysed, over the last decade or so, by an industry group called GeSI (the Global e-Sustainability Initiative). I want to think about what we can do in the near future here, so let’s take some data from its SMARTer 2020 report which had that time horizon. (A later GeSI report, which is keener to accentuate the positive, looks forward towards 2030, but doesn’t change my conclusions in this post.) I’ll draw, too, on analysis I did a while back for the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

Reasons for alarm – direct effects

On the downside, ICTs’ contribution to energy consumption is growing faster than that of any other economic sector.

Between 2002 and 2011, GeSI’s SMARTer 2020 report estimated, carbon (and equivalent) emissions from the ICT sector which contribute to climate change rose by more than 6% each year. Up to 2020 it expected them to rise by a further 3.8% a year (and by more or less the same volume as in the previous decade). Growth was (and was expected to remain) fastest in data centres (an increase of over 7% p.a. anticipated between 2011 and 2020) but still significant where networks (4.6%) and devices (2.3%) were concerned. Overall, the report implied that ICTs’ contribution to global emissions would rise from 1.9% to 2.3% between 2011 and 2020.

Reasons to be cheerful? – indirect effects

GeSI is an industry group, so it’s not surprising that it stresses the upside: the indirect benefits it sees from increased energy efficiency brought about by ICTs.

On the upside, then, it claimed, the ICT sector could enable much higher savings in emissions – up to seven times as much – mostly by improving the efficiency of using energy. The most important areas for improvement it identified were the power sector itself, transport, agriculture, construction and manufacturing. The most significant type of activity in which it saw efficiencies arising was ‘process, activity and functional optimisation.’

Can we juxtapose the two?

GeSI argues that increased energy consumption from the manufacture and use of ICTs is counterbalanced by reduced energy consumption resulting from the ways we use them. I don’t dismiss this argument but there’s a fundamental flaw in it, which is that we can’t really juxtapose the two. They’ve separate causes, they’re separate effects and, what’s more, one’s certain while the other’s not.

On the downside?

The ICT sector’s use of energy is growing for two main reasons. First, more people use more devices more of the time to do more things. More people need more power to run those more devices. Second, cloud computing is rapidly growing the volumes of data traffic exchanged between end-users and the energy-intensive data centres that are the cloud’s embodiment.

Use and data traffic grow as more people go online (which we all want to see). They grow with cloud computing. And they’ll grow much further with the Internet of Things. All trends that lead to more frequent use of more devices, higher volumes of data traffic, more extensive and more capable estates of data centres, and greater energy consumption. (Energy consumed by individual devices may fall as cloud use grows, but those devices are adding further functions: see your smartphone).

These outcomes are, as near as can be, certain. We must expect energy consumption from the ICT sector to continue to increase over the next decade. The challenge for the industry is therefore how to mitigate the energy emissions that result.

And on the upside?

The greater benefits that GeSI predicts are much less certain. They don’t result from millions of people doing more with their devices, but, if they happen, from governments and corporations using ICTs to change big systems which are themselves outside the ICT sector. Systems and businesses that generate energy, run infrastructure, make products, control urban environments, manage transport systems, and so on.

Whether and how far those changes happen depends on the economics of those sectors. Very big investments are required, so the cost of energy’s a major factor. If fracking reduces the cost of fossil fuel, which is already lower than expected, investments in efficiency look less essential. And not all governments and corporations have the political will or the resources to invest in them. The challenge for the ICT industry is persuading them they should.

We should, as elsewhere, base policy not on what ICTs can do here but on a reasonable assessment of what’s likely in the messy world we really live in. Which is why I’ve used the figures on consumption and potential savings from GeSI’s 2020 report (rather than that for 2030) in this blog. If we want to know what is happening now and is likely to happen soon, rather than what might happen in ideal circumstances, we must learn about this fast. We can test reality against aspiration by comparing what happens between now and 2020 with GeSI’s predictions.

And the third type of effects?

There’s a third set of effects we need to bear in mind – which the literature calls ‘rebound effects’. Two examples.

What happens if we make ICTs more capable (as we are doing), if we reduce the energy consumption of individual devices (as we should) and if energy costs therefore fall (as they could do)? Why! Demand will match supply! More people will use more devices for more time. Greater efficiency, especially if it carries financial savings, is more likely to increase consumption than reduce it.

And what happens if people work from home rather than from offices? Why! They’ll have more leisure time! In which they’ll consume more energy – heating homes, using online devices, travelling for pleasure rather than for work, freelancing as well as working for employers.

So what to do?

As with so many aspects of the Information Society, we need to get beyond a contest here between upsides and downsides – between the idea that ICTs do good and the idea that they do harm – and grasp the complexity of what they’re doing to our economies, societies and cultures.

ICT use will grow and add value to people’s lives. More energy will be consumed as a result and, since energy in the medium term (at least) will continue to be fossil-fuelled, this will add to climate change.

ICTs can improve the efficiency of other sectors and of systems that are central to how economies and societies work. That is to be encouraged. But it is by no means inevitable that this will happen or that it will reduce energy consumption overall.

Above all, this should not be seen as a trade-off between the two, regardless of whether GeSI has its numbers right or wrong. There are two challenges here – to mitigate the growth in energy consumption from direct effects; and to maximise the energy savings achievable through indirect effects. Both matter.

How we might go about them will be the theme of next week’s blog.

David Souter is a longstanding associate of

David Souter is a longstanding associate of