Malaysia held its 15th general election in November, which ended in cautious optimism as a unity government, led by reformist Anwar Ibrahim as the prime minister, was eventually formed following a hung parliament. Given the polarised electorate, the onslaught of hate speech on social media before and after the election contributed even further to political divisions. Ahead of the election, the Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ), Malaysia, in collaboration with Universiti Sains Malaysia, Universiti Malaysia Sabah and University of Nottingham Malaysia, launched a hate speech monitoring project called Say No to Hate Speech. It involves two components of monitoring and rapid response. The project also allows the public to report hate speech through its website. It is now gearing up to monitor the six state elections in Malaysia due to take place this year.

CIJ is a non-profit organisation that aspires to a society that is democratic, just and free where all people will enjoy free media and the freedom to express, seek and impart information. We spoke to Wathshlah Naidu, CIJ’s executive director, and Lee Shook Fong, programme officer, about this project and its broader possibilities and implications for a less hateful future.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What were the origins and goals of the ‘Say No to Hate Speech’ project?

Wathshlah Naidu (WN): We started the project in the second half of 2022 to track the increasingly toxic narrative in social media spaces in Malaysia. We observed this following the ‘Sheraton Move’ political crisis – which led to the fall of the 22-month-old Pakatan Harapan (PH) government in 2020 – and the state elections in 2022. There are three main narratives that were often stoked in this divisive discourse, which are called the 3Rs — race, religion and royalty. We also saw many instances of gendered narratives, particularly targeting LGBTIQ communities, as well as harmful speeches targeting the refugees and migrants community.

We wanted to see if there was an escalation of these narratives in the lead-up to the general election, as well as beyond that. These are the questions that we asked ourselves: Who are the actors behind the hate speech? How is it done? What kind of messages are disseminated? Which platforms are affected or mainly used to amplify it?

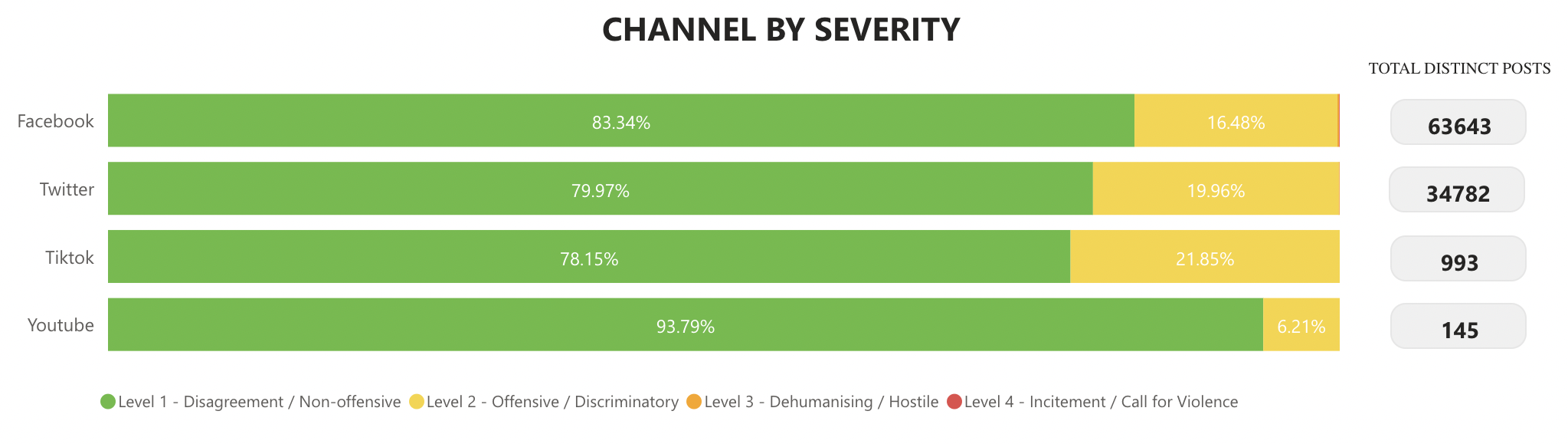

The platforms involved in this project are Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and TikTok. Our tool is able to monitor social media content in three languages: Bahasa Melayu (Malay), English and Mandarin.

Why did you choose these four platforms? And do you have any plans to monitor in more languages in the future?

WN: In terms of viewership, we initially decided on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram, as they come highly ranked. However, after observing the appeal of TikTok in helping the narratives of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to claim power in the Philippines presidential elections, we replaced Instagram with TikTok. I think this is one of the smartest moves we have made, given how much attention TikTok gained during the last general election.

Right now there are no plans for additional languages as it's rather resource-intensive. We have, however, attempted to ensure that some of the resources we’ve developed to create awareness on disinformation and hate speech are available in other languages too, including Tamil, Iban and Kadazan-Dusun.

Who are the actors often engaged in hate speech and misinformation?

WN: We look at five categories of actors: political parties, politicians, media, government agencies and key opinion leaders. For the politicians, we developed criteria such as geographic and gender representation in order to capture the political narratives in the country as accurately as possible. We observed that the media has such a high influence on social media, and the different ways they engage in digital spaces, compared to offline spaces. We included key opinion leaders who often leverage 3R issues to sow discord. We also decided to include key state agencies as they are often the platforms used by the state to propagate certain narratives.

How did the pilot of this project go? What did you learn from it?

WN: We initiated a pilot between August-September 2022 where we trained 23 human monitors from Universiti Sains Malaysia and the University of Nottingham to test the framework and the tool. From this pilot, we managed to do some initial analysis but unfortunately, we did not have time to do a full analysis – since the parliament was dissolved in October 2022, we had to go into full-on election monitoring mode. Within a short time, we managed to train additional human monitors, assigned leads, allocated teams and fine-tuned and fixed the glitches of the tool. This is for the monitoring part where we worked with 49 monitors.

However, we were still struggling with the rapid response part of the tool. To navigate this, we worked with civil society partners who were connected to the communities in these three areas: 3Rs; gender and LGBTIQ; and refugees and migrants. With them, we developed a set of FAQs to help the public understand these communities as a way to change the broader mindset. We also worked with these partners to develop communications materials as well as guidelines for the media. At the same time, we also spoke at panels and other engagements about this initiative and spread awareness. We also thought the initiative should not be one-sided. On top of monitoring and rapid response, we also encouraged the public to report instances of hate speech.

We learned that hate speech often involves some level of disinformation. For this tool, however, we decided not to do fact-checking as this would require a huge amount of resources. Instead, we linked our team to fact-checking initiatives such as JomCheck, supported by Google. Whenever our team comes across instances of disinformation or misinformation, we would send it to JomCheck to get the information verified. This collaboration has proven useful as we can limit our resources and keep track of the narratives at the same time.

How rapid is the response?

WN: It is never rapid enough! However, as we were working with a number of CSOs (civil society organisations) we were able to coordinate our responses and action in a more timely manner. The rapidness depended on the severity as well as the planned action. For example, in the case of doxxing we acted immediately and within 24 hours our partners checked in with the respective refugee and migrant communities. Statements took between 24 and 48 hours to be issued.

What are the main trends and patterns around hate speech/misinformation that you saw in the lead-up to the election?

WN: We saw some unexpected trends over the monitoring duration. We expected Barisan Nasional (National Front) – the oldest centre-right and right-wing coalition that had governed Malaysia for the past 61 years until 2018 – to monopolise the digital space as they had a history of employing a huge number of cyber troopers. But what we found, especially after monitoring TikTok, was that it was the PAS (Malaysian Islamic Party) that had been putting out the highest level of hate narratives before the election. They started out by leveraging Malay supremacy sentiments to potential voters and telling them that by voting for the opposition parties like Pakatan Harapan (the Alliance of Hope) and DAP (Democratic Action Party) – which are made up of multiracial and multi-ethnic groups – they would lose this privilege of supremacy.

The dangerous narratives also started to come out in droves post-election. Users started to put up videos on TikTok warning of a repeat of May 13 – a bloody racial riot in 1969 which involved violent clashes between members of the Malay and the Chinese communities in and around Kuala Lumpur after opposition parties supported by Chinese voters made inroads in an election – if non-Malay Muslim parties were to govern Malaysia. This narrative is not new, but it was especially amplified on TikTok, which is a whole new platform, during this election period. It also imploded partly because of the fact that this time, the minimum voting age was lowered from 21 to 18, so it was apt for them to target these hate narratives on a platform where young people congregate the most.

We also monitor not only the original posts but also the responses and comments. We observed that when politicians or political parties put up any kind of disinformation or hate speech, the severity level is always within Level 1 and Level 2. However, the responses and comments can escalate to Level 3 and Level 4.

Lee Shook Fong (LSF): We also learned from the pilot that we needed to make a distinction between the original posts and the responses, and the contexts around them to assign the severity levels. There were multiple layers of monitoring and tagging involved in the process.

Most of these responses are organic, but have you seen any coordinated efforts of hate speech and disinformation?

WN: We have identified a few accounts that have pushed certain narratives, but as mentioned, they have become more sophisticated. These people have now coordinated in such a way that it is very difficult to distinguish unless a complete network analysis is conducted.

There are a few patterns. On Twitter, we can see these accounts are often following each other (coordinated accounts). They also share the same narrative and similar language, tone and voice. On TikTok, we identified many young content creators and a few paid partnership content.

LSF: Our monitors also found that whenever one political party mentioned something and received comments from the opposing coalitions, the party would soon come to realise that there was a concerted effort going on. They would then improvise their messaging as a way to counter and respond.

WN: It is also important to note that these coordinated accounts are just the first layer. They can come in and fill the space with these racial narratives, but it was the general netizens who gave “oxygen” to the posts by sharing and amplifying them. To quote a monitor, “it’s almost like herd mentality” with the UGCs (user-generated content) mainly echoing similar sentiments.

Have you also seen any coordinated effort of pushback against hate speech and misinformation?

WN: Not necessarily. Any attempts to push back were mainly organic and were UGCs. The pushback was also mainly on Twitter and less so on other platforms.

Does the tool also monitor the response of social media platforms to hate speech and disinformation?

WN: We sent our analysis to the social media platforms for them to take action, such as to moderate content or to be informed of the contexts. One of the recent examples was the removal of May 13-related content on TikTok. However, with the mass layoffs across many tech companies such as Meta and TikTok, we observed their content moderation departments are also significantly affected, hence the delays on their part.

One of the biggest challenges with these platforms, as well as with us with this tool, is language. As of now, the keywords are still building up. On top of that, we have to constantly be aware of new acronyms and terminologies and the many ways the different keywords can be spelt. Furthermore, these keywords need to be contextualised to the Malaysian political and social sphere. For example, if we happen to scrape data from Indonesia that falls under these keywords, we have to let the platforms know that the context is different.

In the future, we are also going to have more conversations with Meta, Twitter and TikTok where we will be sharing our outcome once our report is launched. At the same time, there is also a need to get the government to engage with these platforms and to focus on content moderation or other forms of minimising the negative impacts of these spaces, rather than pushing for new and additional forms of regulation, by way of new laws.

What happens when hate speech is detected and requires immediate intervention?

WN: We had an instance where the Immigration Department of Malaysia issued a call for people to report sightings of undocumented migrants. During this time, we observed a spike in doxxing happening online. We then channelled the information to our partners so they could check on the communities and provide support in many forms, including legal, if necessary. [To support its human monitors, CIJ has planned for extensive means of support, ranging from legal to psycho-social. CIJ is also co-chair of the Freedom of Expression (FoE) coalition of CSOs in Malaysia, and also manages a FoE legal defense fund.]

We also learned it is very difficult to counter hate speech as it happens, so we have to think about measures to protect affected groups as well as preemptive narratives. This can include FAQs on trending issues and issuing statements. As such, the rapid response part of the tool is very critical to make sure there is no escalation on these issues.

What we found especially disconcerting was the amount of hatred these young content creators had been spewing on social media. I believe this does not come off the cuff; it has to be coordinated. It is especially scary given they are first-time voters and are grappling with some narratives to shape their political beliefs, and what they are able to hold on to is hate. There needs to be better collaboration between platforms and the government with regard to content moderation, as well as the need to set up a commission of independent experts and various stakeholders to understand where this is coming from.

At the same time, we need to look at hate speech in the longer term – why does this happen? Who is behind it? We need to come up with new narratives and set the right tone, and this can be done through education system reform and similar initiatives.

We have to take more concerted, non-punitive, and beyond legalistic efforts to address the prevalence of hate speech in the country. If law enforcement is involved, this means the laws that are going to be used on the perpetrators will be the same laws that we have been advocating to repeal such as the Sedition Act and a number of penal code provisions. At the same time, we have been demanding reforms for Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act for years. The ideal point of reference would be the Rabat Plan of Action – which considers the distinction between freedom of expression and incitement to hatred through some threshold tests and recommendations – where we could think of ways to see beyond the legal system and framework to counter hate speech.

Read part two of this interview here.