Oil was reportedly first discovered in the Niger Delta, Nigeria’s main hub, in the 1950s, making the country the main exporter from Africa and the world’s tenth largest crude oil reserves. For the people living in the region, this doesn’t mean wealth. On the contrary, the legacy that decades of oil industry has left behind is multiple spills, widespread environmental pollution, the destruction of livelihoods and violent repression of protests by the government.

Raising the civil society’s voice against the issues is the motivation of the Media Awareness and Justice Initiative (MAJI), an independent media group based in Nigeria that is using new low-cost technologies to monitor air pollution. With the data created, they are helping local villages hold big companies accountable after decades of exploitation in the Niger Delta.

Crude oil pollution has affected community lands, water and air in a region where people’s occupations are primarily farming and fishing, explains Okoro Onyekachi Emmanuel, the lead of MAJI’s Soot Mapping project. Mangrove forests, which provide breeding grounds for fish, sustaining a whole ecosystem and many livelihoods, have been seriously impacted. By installing solar power-based air quality sensors across 15 urban and rural communities in the region, MAJI built a platform for citizen data collection and strengthened local people and organisations in their struggle against oil pollution.

Data-driven proof and citizen-generated evidence of these negative impacts are much needed in a region where crude oil is mainly extracted under a joint venture between the Nigerian government and multinational companies, such as Shell, Total, Agip, Chevron, ExxonMobil and Texaco. Such foreign firms are often more protected by the state than the country’s own population. “We are trying to make them care,” he summarises, after working with marginalised groups living in rural and urban communities in the Niger Delta region for over 15 years.

Mapping the dangers of oil pollution

Images of major oil spills in Nigeria were shared around the world when two local communities decided to bring a lawsuit against fossil fuel giant Shell’s parent company, SPDC, in its homeland, the United Kingdom, calling the attention of media outlets like The Guardian and Bloomberg News. Shell’s oil plants have caused and “continue to cause, long-term contamination of the land, swamps, groundwater and waterways” in Ogale, claimed the law firm representing both communities in British Courts.

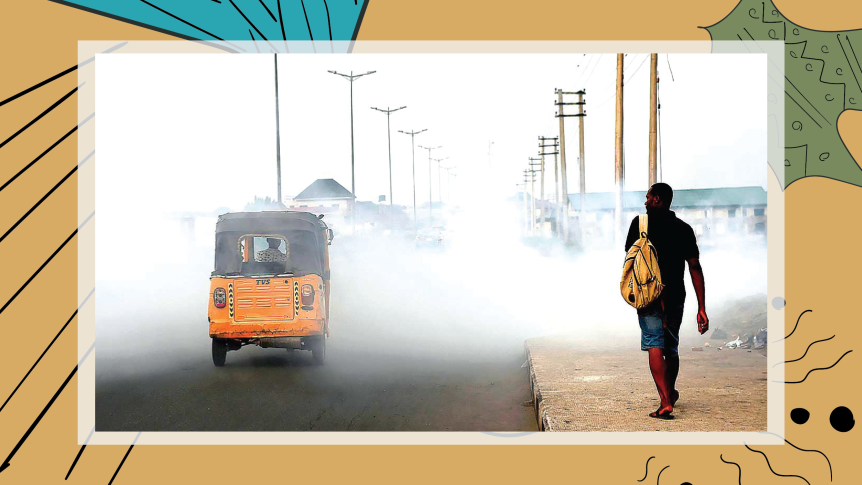

While many spills have been captured by photos, and oil pollution in Ogale’s water wells was carefully documented by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2011, there was another negative impact of the oil industry that is invisible to human eyes and was harder to prove: the air pollution.

Measured in the size of PMs, which stands for “particulate matter”, air pollution particles can be, in fact, so small that they pose a huge public health concern. “Particles that are 2.5 microns (PM 2.5) or smaller are considered especially dangerous to human health because they can travel into the bloodstream from the lungs, bypassing many of our body’s defenses,” explains this article from Molekule blog.

PM 2.5 soot particles are precisely among the air pollutants present around the Niger Delta in disturbing levels, as MAJI’s project helped to document and prove.

MAJI’s Soot Mapping project uses low cost and open data technology to monitor air pollution in Rivers State, the oil nexus of the Nigerian oil industry. The project idea emerged from challenging times: looking at the COVID-19 pandemic and how quantitative data was used to increase awareness about an invisible virus, they started to think about how locals could generate their own data and call attention to air pollution that is not visible.

“When there is a spill, you can see it, you can say that was caused by a certain number of barrels. In the air it was more challenging,” explains Emmanuel. “So, we were in a need for data, for sensor devices that could allow us to do analyses over time.”

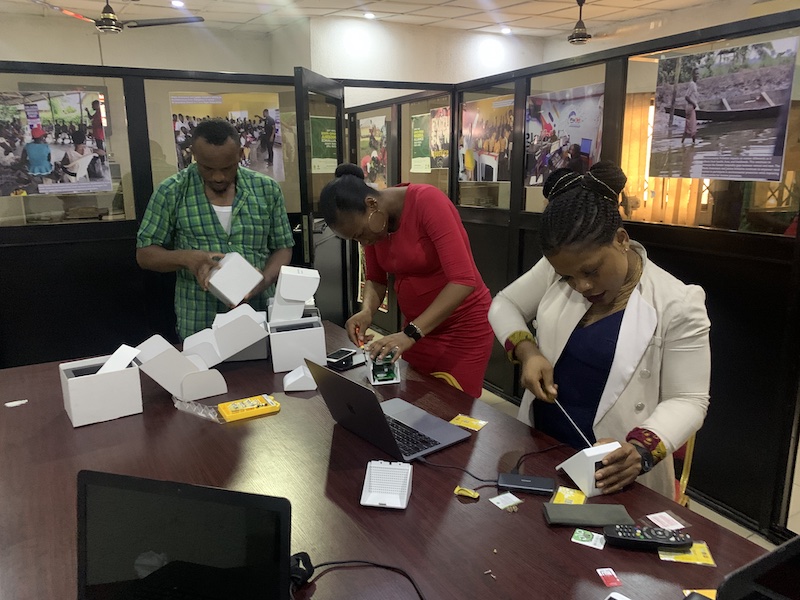

To build the project, MAJI started with the training of 20 grassroots civil society community-based organisations on environmental data collection, analysis and use. They also deployed air quality sensors with mobile data connectivity during the project’s duration from November 2021 to May 2022. Initially 10 sites were covered by the sensors, and this was later expanded to 15 locations in a partnership between MAJI and the Open Culture Foundation (OCF), a non-profit organisation founded by members of Taiwan’s open source community that donated Taiwanese air sensors that can monitor PM 2.5 to MAJI. The two organisations, both APC members, have been an active voice to speaking up against pollution.

Low cost technology enabling awareness raising

Over time, the sensor-network data was fed into an online air quality data collection portal, developed to gather the information and, by using graphics and pictures, provide a visual analysis of the pollution level.

“Since 2015, rural and urban communities have identified a constant increase in the level of PM 2.5, PM 1.0 and PM 10 amorphous carbon and an alarming deterioration in air quality,” explains MAJI in its report to the APC’s Connecting the Unconnected initiative, which provided financial resources for the MAJI project. The submission points out that, “Citizen reports and further research into the problem showed that the increase in PM 2.5 pollution was a result of the constant flaring of gas by oil companies and artisanal refining of crude oil.”

With the evidence created by the project, MAJI has been campaigning and mobilising radio shows to raise awareness among the population as well as among local and global partners. “Communities and radio stations are showing interest. You can see people posting PM 2.5 levels in their community, this is becoming something just like traffic updates,” celebrates Emmanuel.

Just like this morning, Our airnote detects an unhealthy air in Buguma,Asari Toru LGA https://t.co/rD9T4gUDel pic.twitter.com/oYECm4yjWD

— Ifunanya (@Rarebreedtype) July 31, 2022

While the population reclaims its right to a better understanding of pollution in its environment, MAJI also continues to use the data generated by the project for policy engagement and discussions with government agencies and policy stakeholders.

With livelihood deterioration and large-scale poverty, many people were forced to engage in artisanal refining of crude oil, which continues to seriously impact the community land, water and air, creating a negative cycle. And the data gathered by the project can help to prove it. “You can notice huge spikes in the levels of PMs, showing that actually there are ongoing activities polluting the region. Using the monitoring, communities can see where and when these spikes are happening,” he explains, backed by data gathered by MAJI. “And by so doing, the government cannot ignore them and could be able to shut down clandestine refineries.”

The spikes show that oil pollution is not a problem of the past, but something that keeps threatening the region. To MAJI, one of the most significant changes that has been identified during the project is how the Ogale Community in Rivers State is now using qualitative and quantitative data about the air pollution in the pursuit of its legal case against SPDC in the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom for the pollution of their environment and destruction of community lives and livelihoods.

Community networks will strengthen the use of open data

When discussing MAJI’s dreams for the future, Okoro Onyekachi Emmanuel considers the impact celebrated so far as a pilot for bigger flights: “We have only 15 communities covered. This is a sample number used as a way to understand what the challenges were. We hope to expand it. There are over 200 communities that are spread across several locations in the Delta region.”

Aside from expanding the sensor network, MAJI also aims to improve the connection among the people living in the monitoring sites with a bottom-up approach. “We have identified the need to provide open and affordable internet access to rural and urban poor communities across the region. And the provision of community networks could strengthen the use of open data while bridging the digital gap of people who are seen as economically disadvantaged,” explains Emmanuel.

The organisation is now carrying out a crowdfunding campaign and searching for financing alternatives to enable the deployment of self-sustaining community networks in rural and urban communities in the region. “In addition, we can encourage young people to develop their own air quality devices, because we know that with minimal training, people can be taught,” plans Emmanuel.

This piece is a version of information shared by MAJI and its representative Okoro Onyekachi Emmanuel as part of the project "Connecting the Unconnected: Supporting community networks and other community-based connectivity initiatives" for the Seeding Change column, which presents the experiences of APC members and partners who were recipients of funding through "Connecting the Unconnected" catalytic grants and of subgrants offered through other APC projects and initiatives.

Did this story inspire you to plant seeds of change in your community? Share your story with us at communications@apc.org.