This article was originally published in Issue 1 of Southern Africa Digital Rights, an online publication produced under "The African Declaration on Internet Rights and Freedoms: Fostering a human rights-centred approach to privacy, data protection and access to the internet in Southern Africa" project.

Zimbabwe remains one of the countries in Southern Africa with expensive internet access and various factors contribute to this including the macroeconomic policies, unstable currency and political interests. Due to the hyperinflationary environment, limited access to foreign currency and also the taxation of the telecommunications industry, it is therefore difficult for citizens to enjoy affordable internet. [1] This has therefore continued to widen the digital divide in Zimbabwe particularly between people with low income levels and those with higher income levels and also between those in rural areas vis-a-vis those in urban areas.

The internet infrastructure is controlled by the private sector, though the government dictates and influences the pricing systems for telecommunications from voice, short messages services, to internet costs. [2] The regulator of the telecommunications industry, the Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (POTRAZ), is responsible for setting the prices of mobile data using its pricing index. Following public outcry in December 2021 over the high cost of data, POTRAZ highlighted that, “Our principle for tariff reviews have always been cost-based, hence as cost of service changes we always try to ensure that service provision is aligned to the costs incurred by the service providers.” [3]

According to NewsDay, from 10 March 2021, the cost of 8GB of data was pegged at US$18, with 50GB of private internet data from Econet Wireless rising to US$47. In July of 2021, increases were recorded bringing the cost of 8GB to US$23, and 50GB rising to US$73. [4] The internet service providers bemoaned the “imposition of an additional 10% excise duty across all internet and VoIP packages effective 1 March 2022”, which caused a substantial increase in the costs of data in March 2022. [5] Media groups raised concerns about this decision, which impacts on citizens’ access to information and online participation. [6]

Following a petition submitted to Zimbabwe’s parliament by MISA Zimbabwe, calling for internet affordability in Zimbabwe, and a directive to POTRAZ by the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee, POTRAZ convened a multi-stakeholder meeting on 9-10 May 2022 under the theme, ‘Ensuring operator viability and service affordability-the balancing act and challenges.’ The meeting underscored that several stakeholders had a role to play to facilitate universal access to the internet, including the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, the Ministry of Finance, the Zimbabwe Electricity Supply Authority (ZESA) and the Ministry of Local Government. [7]

Most Zimbabweans access the internet through mobile data and what are called bundled packages specifically for social media platforms like WhatsApp, Twitter and Facebook, while others use private Wi-Fi bundles. According to POTRAZ director, Gift Machengete, data in Zimbabwe is pegged at 0.010 cents per megabyte which translates to US$10.00 per gigabyte.

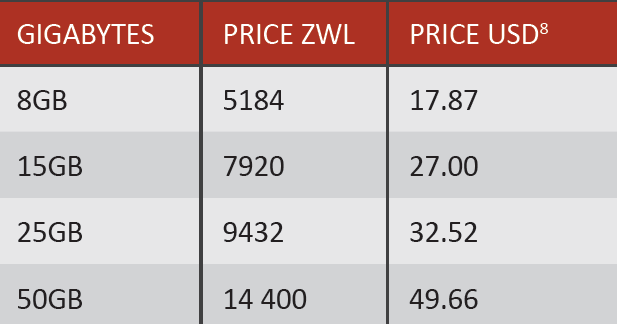

Recently, on 19 May 2022, one of the mobile operators, Econet Wireless increased its data tariffs by 20 percent. The new prices of data are as follows:

While the above costs might seem cheaper in US dollar terms as compared to the previous months, what should be noted is that Zimbabwe is yet to dollarize and what has increased is the official exchange rate between the local currency and the US dollar. On the other hand, the income levels of the majority of citizens remain the same despite an increase in the cost of living and access to the internet. [9]

Residents of border towns are now relying on neighbouring countries’ mobile internet services, which are cheaper and more reliable. A market for foreign SIM cards is therefore thriving in those areas. [10] As the country’s economic situation deteriorates, the cost to connect to the internet will increase.

Online surveillance

Social media has become a site for political and social debates and has also been used for organising and mobilising politically. [11] Irked by rising online activism and internet-based organising, the government announced in November 2021, through the Ministry of Information, Publicity and Broadcasting Services, that it set up a social media monitoring unit. [12] The Minister of Information, Monica Mutsvangwa, was quoted saying: “We have actually come up with a cyber-team that is constantly on social media to monitor what people send and receive since we cannot wish social media away.”

While no further information was provided about the unit and the monitoring tools they use, what is clear is that there is some form of mass surveillance of social media and social media users in Zimbabwe, which appears to be a violation of the right to privacy online.

The monitoring of social media and the use of social media brigades has historically increased during sensitive political periods, such as in the run up to elections (Zimbabwe has general elections in 2023). [13] Lawyers, human rights defenders, journalists, and opposition political activists are subjected to online harassment to silence legitimate criticism of the ruling party or government. [14]

The Cyber and Data Protection Act

In December 2021, Zimbabwe enacted the Cyber and Data Protection Act, which also amended the Criminal Law Codification and Reform Act, the Criminal Procedure and Evidence Act and the Interception of Communications Act. The law provides a comprehensive framework on data protection and privacy, by including the rights of data subjects, regulating the processing of sensitive data and also providing for notification in the event of a security breach. [15] The law therefore codifies the right to privacy as provided for in Section 57 of the Zimbabwe Constitution.

The law also establishes the Data Protection Authority, by mandating POTRAZ to establish conditions for the lawful processing of data. Since February 2022, POTRAZ has started implementing the provisions of the law, [16] by requesting all data controllers and processors, that hold or process the data of more than 30 people, to provide information on the following:

- What data was collected and processed and for what purpose.

- Whether a data protection officer was appointed and the professional credentials of the appointed officer.

- The address of the data controller and proof of residence.

The protection of personal data and information remains contested, as the Zimbabwean government has several data centres in the country, since before adopting the data protection law, raising concerns of unauthorised access to personal data. [17]

Arrests for online conduct

The Cyber and Data Protection Act has already been used to prosecute individuals for online conduct with two people having been arrested for cyberbullying. Cyberbullying is defined as “unlawfully and intentionally by means of a computer or information system, generating and sending any data message to another person or posting any material whatsoever on any electronic medium accessible by any person, with the intent to coerce, intimidate, harass, threaten, bully or cause substantial emotional distress or to degrade, humiliate or demean the person of another....”

On 19 May 2022, a Nyanga resident was charged with cyberbullying for allegedly using foul language to describe the Zimbabwean ambassador to Tanzania and his wife in a WhatsApp group. [18]

On 24 May 2022, television actor David Kanduna was reported to have been arrested and fined for cyberbullying after recording a police officer being jeered at one of the local universities and posting the video to WhatsApp and Tik Tok. [19]

Concerning these cases and the definition of cyberbullying, the danger is that the Cyber and Data Protection Act may have resuscitated criminal defamation, which was outlawed by the Constitutional Court in 2014.

A 23-year-old woman, known for marketing sex toys on TikTok, Twitter and Facebook, was also arrested on 16 May 2022 for allegedly exposing children to pornographic material and violating the Customs and Excise Act. [20]

Internet slow down

On 20 February 2022, the Citizens Coalition for Change political party was officially launched in the Highfields area of Harare, in the run up to by-elections scheduled for 26 March 2022.

Netblocks recorded a significant slow-down of the internet on the day, which limited access to online coverage of the launch and the sharing of videos and images on social media platforms. [21]

POTRAZ indicated that the government had not throttled the internet in any way on the day and instead said that a technical issue had been caused by the large number of people at the launch attempting to access the internet at once. [22]

MISA Zimbabwe criticised the internet slow-down and highlighted that internet connectivity should not be unjustifiably restricted so that people can exercise their right to access information and also exercise political rights, especially during election periods. [23]

The issues spotlighted clearly indicate that there is a need for further advocacy to promote digital rights. There are several factors, some legal, some political and some economic, that continue to impact the exercising of rights online, particularly free expression, the right to privacy and access to information. At the same time, with the enactment of the Cyber and Data Protection Act, Zimbabwe is one of only nine countries in southern Africa with such a framework.

Notes:

[1] Enacy Mapakame, “Telcos record 247BN revenue in Q2”, The Herald, October 12, 2021 https://www.herald.co.zw/telcos-record-247bn-revenue-in-q2/

[3] https://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/potraz-defends-datatariff-hikes/

[4] https://www.newsday.co.zw/2021/07/exorbitant-internet-costschoke-zimbos/

[5] https://itweb.africa/content/rW1xL759kpO7Rk6m

[6] https://zimbabwe.misa.org/2021/10/28/increase-in-data-tariffs-impediment-to-access-to-information/

[7] http://easterntimeszim.org/2022/05/11/ict-parliamentary-portfolio-slams-finance-ministry-rbz/

[8] At official rate of 1:290 as at 30 May 2022.

[9] Zimbabwean teachers strike amid pandemic and high inflation, AP News , https://apnews.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-business-health-africa-pandemics-0d70cfa5d5b6c23c3826498e331d3378

[10] https://restofworld.org/2022/black-market-sim-cards-zimbabwe-border-work-hub/

[11] Many social movements groups used hashtags to organise such as #This Flag or #ShutdownZim (2022)

[12] https://www.newsday.co.zw/2021/11/govt-sets-up-team-to-monitor-social-media/

[13] Charles Moyo ‘Social media, civil resistance, the Varakashi factor and the shifting polemics of Zimbabwe’s social media “war” Global Media Journal 2019.

[14] https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/zimbabwean-regime-shifts-oppression-to-social-media/2146273

[15] https://zimbabwe.misa.org/2021/12/06/analysis-of-the-data-protection-act/

[16] https://businesstimes.co.zw/potraz-enforces-data-protection-act/

[18] https://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/former-army-chief-cyber-bullied/

[19] https://hmetro.co.zw/archive/television-actor-kanduna-fined-for-cyber-bullying/

[22] https://bulawayo24.com/index-id-news-sc-national-byo-215629.html

[23] https://www.newsday.co.zw/2022/02/misa-blasts-yellow-sunday-internet-slowdown/