News that the Bulgarian national security agency (DANS) had raided the offices of the State forestry agency in Sofia back in March caught green activists by surprise. Particularly because news suggested that reports by ”ecologists” were the reason for the Hollywood-style action in Bulgaria’s Ministry of Agriculture.

Indeed, members of the For the Nature coalition had been campaigning for months against the non-transparent practice of exchanging cheaper forests for state-owned green areas along the Black Sea coast and in the high mountains, which would immediately be turned into construction development sites. But activists found it hard to believe that their repeated signals to Bulgaria’s law enforcement agencies and parliament and the EU, had actually worked. “The DANS had never budged before,” explained Stefan Avramov of the Bulgarian Biodiversity Foundation, who emailed the coalition’s mailing list. But scepticism aside, the greens had to face the fact that they had once again appeared at the right time and place to topple yet another Goliath breaching the public’s environmental interests. And internet communications had been the catapult in their hands.

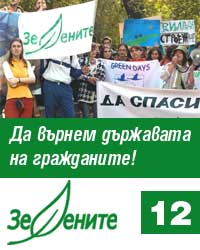

The public had already faced it, with spontaneous citizen actions against the tourist construction bonanza in the mountains and along the Black Sea coast, sprawling from internet chat rooms and the blogosphere onto the streets of Sofia and other major cities since 2007. Two years later, flying on the wings of their rediscovered ability to set the public agenda, activists were ready to claim a stake in the country’s representative democracy system and run for elections with their own political party called Zelenite (the Greens).

Green politicians also sprout in Hungary

Success in the face of the political establishment is not unique to Bulgarian green activism. In an almost identical scenario, Hungary’s green movement has also launched a new political party called Politics Can Be Different (in Hungarian: Lehet Más a Politika!, or LMP). ). In a dramatic last-minute move, LMP registered for the June 7 European Parliament elections, in coalition with the Humanist Union of Hungary.

The new party was built upon a broad public movement, which has catapulted former Constitutional Court Chair László Sólyom to President back in 2005 following popular protests against the construction of a NATO radar station in the Mount Zengõ protected area.

If common roots in the green movement is the first striking similarity between Zelenite in Sofia and LMP in Budapest, their reliance on the internet and online networking is certainly the second, beginning with the large-scale internet presence, through which both parties imposed to meet their respective countries’ formal requirements for participation in the elections. With the help of online signatures and money donations, Zelenite’s last minute happy-ending registration for the EU ballot was not less exciting. And while the two parties’ results (2.6 per cent of the vote for LMP and only 0.72 for Zelenite) were certainly no match for the great expectations and enthusiasm of their supporters, they were read as a distinguishable claim for future presence in both countries by political analysts.

e-networking in actionBoth Zelenite and LMP campaigned aggressively online, aiming to raise their profile and consolidate support among young voters with internet access, said representatives from Political Capital – a think tank that operates in both countries. Not surprisingly, internet and communication rights have found a prominent space in the Zelenite’s programme . The party’s campaign and election ballot featured Bogo Shopov, one of the faces of the online communication rights struggle in Bulgaria. This aspect of Zelenite’s campaign reflected a powerful public reaction against the infringement of freedom of both online and traditional forms of expression by state bodies and new policies aimed at the establishment of data retention.

e-networking in actionBoth Zelenite and LMP campaigned aggressively online, aiming to raise their profile and consolidate support among young voters with internet access, said representatives from Political Capital – a think tank that operates in both countries. Not surprisingly, internet and communication rights have found a prominent space in the Zelenite’s programme . The party’s campaign and election ballot featured Bogo Shopov, one of the faces of the online communication rights struggle in Bulgaria. This aspect of Zelenite’s campaign reflected a powerful public reaction against the infringement of freedom of both online and traditional forms of expression by state bodies and new policies aimed at the establishment of data retention.

But similarities do not stop here. Both parties had their electoral lists populated by young faces, well familiar to the public with their activist past: people like András Schiffer, a Védegylet activist since Sólyom’s presidential crusade, and Andrey Kovachev, the chair of Balkani – Sofia and a veteran from the media battles against the construction lobbyists. E-networking activists linked to APC’s members in Hungary and Bulgaria, were actively involved as well. BlueLink had at some point two of its Board members in Zelenite’s leadership, and its chairwoman Natalia Dimitrova ran for election in the European Parliament on Zelenite’s ticket. In Hungary Green Spider members were involved with ELP since its very start.

Green politics not everyone’s cup of tea

But the transition to real politics is not to everyone’s liking within activists’ ranks. Prominent Hungarian groups like HuMuSz, FoE Hungary, and Nimfea, have chosen not to get formally involved with the party, although some of their members and leaders are part of it. Some activists fear that party politics will disturb their actions in Bulgaria as well. “The party is draining too many resources and energy from the activist sector, and may leave it bloodless and disheartened if it fails,” said Ilian Iliev of the Public Environmental Centre for Sustainable Development in Varna, Bulgaria. Iliev, another BlueLink founder and Board member, has been a founding member of Zelenite since its very start, but has refused to leave his civil society work to campaign for elections.

Such a pessimistic scenario is not at all unlikely, argued Petr Jehlicka, a UK-based researcher of post-socialist and civil society developments. Jehlicka warned that a similar move towards party politics in the Czech Republic during the past years had actually resulted in the loss of human power by NGOs.

But Klara Hajdu, a biodiversity policy officer at the Budapest-based network CEEweb for Biodiversity, sees entering politics as a natural step for the conservation movement. “We have tools and policies to counter pressures on biodiversity, but they cannot manage the complex root causes behind the pressures,” she admitted. NGOs have reached a limit in challenging these causes, and need to engage with politics if they want to move any further.

Defining the political orientation of the new citizen driven parties poses a different set of problems. While LMP has defines itself as a “social environmental” party at an ease, Bulgaria’s new Greens are still reluctant to identify with anything that contains the word social. “Left or right – that is not the dilemma. What we need is a good world – and this is something much bigger then political geometry,” Zelenite’s co-chair Petko Kovachev wrote on a Facebook wall. But this stand and some pro-EU and pro-market economy formulations in the party’s programme raise eyebrows and sharp discussions within and outside the party. Many activists demanding radical social change may be put off by them and perceive Zelenite as just another neo-liberal political offshoot, Jehlicka commented.

Photos: used with permission by Zelenite’s Flickr and “official site”:http://www.zelenite.bg/english